Selçuk Esenbel, Bogaziçi University emeritus professor’s review of the book “A Secular Age beyond the West: Religion, Law and the State in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa ». Edited by Mirjam Künkler, John Madeley, and Shylashri Shankar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

KEYWORDS: secularism, Muslim democracy, conservatism, constitutionalism, Islam, Turkey, St. Sophia, New Year’s celebrations, Christmas

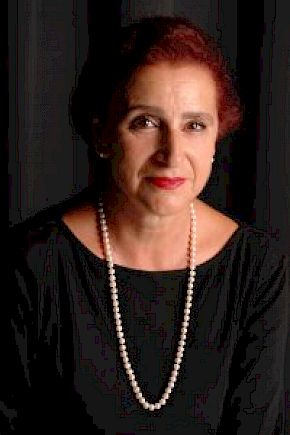

« Reflections from home on secularism and the possibility of muslim democracy » Selçuk Esenbel

« To do justice to the important topic of secularism requires a multidimensional perspective.

A Secular Age beyond the West: Religion, Law and the State in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa answers this need by looking at secularism from different cultural and geographic experiences through the expertise of scholars who are able to dive in depth into primary sources. Editors Mirjam Künkler, John Madeley, and Shylashri Shankar brought together authors from the disciplines of sociology, history, political science, and religion who are country experts working in the primary languages and with the primary data. The resulting collection of essays is uniquely cohesive by virtue of the fact that all authors respond to Charles Taylor’s call to probe the unity of the North Atlantic world in featuring a condition that he calls Secularity III, and in pursuing a shared social scientic approach in doing so, which is outlined by Philip Gorski in chapter 2 of the volume, “Secularity I: Varieties and Dilemmas.”1 This review focuses on Asli Bâli’s chapter on secularism in Turkey, “A Kemalist Secular Age? Cultural Politics and Radical Republicanism in Turkey” (234–64). In studies of comparative secularism, Turkey is often treated as a case para- digmatic for the wider Muslim world, but, as Bâli’s chapter—and, indeed, the whole volume— shows, Turkey diverges signicantly from comparative cases.

The founding of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 and the ensuing Turkish Revolution, as it was known at the time, created a staunchly secular nation-state primarily following the model of the French, and more broadly European, experience since the end of the nineteenth century. Having displaced the traditional Islamic elites among the religious scholars, the religious orders, and the judiciary, the political revolution translated into a signicant effort at diminishing the role of Islamic traditions in the frame of state and society. Turkey’s venture into secularism, embedded in the Westernist orientation of the regime, has remained one of a kind in the Muslim world and has been the subject of blame and praise ever since.

In a short but elegant discourse on constitutions in his book Founding Acts: Constitutional Origins in a Democratic Age, Serdar Tekin reects on the issue by indicating that the people fre- quently do not act as an agent in the process of making a constitution, even if it is for the sake of democracy, and that founding moments are the monopoly of a small elite circle or an authori- tarian hand.2 Tekin’s political philosophical discussions are beyond the scope of this review, but his frame illuminates the current contradictions in Turkey’s secularism and democracy. TThe democrati- cally elected people’s party—the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP (Justice and Development Party), Turkey’s rst Islamist-oriented party, which has held power since 2002—proudly vocalized the desire of its constituency to modify the secular and Western orientation of the Republic and dress Turkey in more Islamic garb. Having brought Islam farther into the public sphere much more than it has been in the past, the party was once expected, both at home and globally, to become the conservative Muslim Democrats of Turkey à la the conservative Christian Democrats of Germany. Instead, the AKP has seriously diminished the legacy of democracy that the secular republican institutions built during nearly a century of evolution. It looks as if the AKP has failed in the management of a democratic order.

The current problems, however, go back to the paradox of the founding moments of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. That moment promised a people-oriented new regime in place of the former Ottoman Empire, which was buried under the debris of the First World War. Instead, it created a top-down revolution of secularism and modernism. Replacing Islam as the vision of the polity, the cadres constructed a new ideology of the Republic popularly known as Kemalism, based on the ideas of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938), the founder of modern Turkey. A former general of the Ottoman army who became the victorious leader of the War of Independence against the major Western powers that had occupied most of the Ottoman territories including the capital Istanbul, Atatürk was elected by the Grand Assembly as the rst president of the Republic of Turkey in the aftermath of the war. Though the term was never ofcially adopted, Kemalism constituted six major principles: republicanism, populism, nationalism, laicism (based on the French model), statism, and reformism (quite typical of late nineteenth-century and twentieth- century nation-state oriented revolutions globally). Even though the leadership and elites in Turkey at the time acknowledged the role of Islamic traditions in the way of life of the people, they did not include Islam in their vision of future progress and modernity.3 Thus secular-oriented Turks were surprised in the early 2000s to face the deep resentment and frustration that had accumulated over generations and was now being strongly vocalized by the AKP.

Tekin’s work is also noteworthy because it explains the heart of my authorial perspective in this essay. As a female and an academic who has served for close to fifty years in the Turkish academy, has chosen Turkey as home, and who perceives the current transformation of secularism in this country, I and that Tekin’s argument resonates with me:

“But philosophy, some philosophy, starts at home,” writes Avishai Margalit in his wonderful work, Ethics of Memory. Margalit’s statement certainly holds true for the kind of theoretical inquiry undertaken in this book. To me “home” is Turkey, a country that has a decisive founding moment. It took place in the early 1920s, when a new republic was founded from the ashes of a collapsed empire. While it was far from the kind of democratic foundation that I argue for in this book, its effects have shaped the history of modern Turkey, for better and for worse, up to the present day.4

Nothing could better describe my attitude about democracy and modern Turkey, including its secularism. I am unconvinced by the derivative versions of the postmodern critique of the Enlightenment as the roots of Eurocentric orientalism/colonialism. I am, likewise, unconvinced by the supercial versions of postmodernism that have inltrated the Islamic discourse of the cur- rent regime and of its intellectual claims that disregard the existential issue of dening individual right and liberty and democracy without recourse to religious doctrine. The recent rhetoric of the government leadership ominously rejects the centuries of Ottoman and republican integration into Western know-how and institutions as “fake modernity,” reminiscent of the revolt against the West in the mind of the prewar National Socialists in Germany and Pan-Asianists in Japan.5

I therefore discuss Asli Bâli’s chapter on secularism in Turkey with the added personal engage- ment with the question of whether conservative Muslim democracy is possible or not under the cur- rent conditions. Bâli’s chapter provides a historical narrative on the transplantation of Western-style secularity in Turkey. Bâli argues that the Turkish experience of secularism diverges from Charles Taylor’s argument about Secularity III as giving rise to plurality and institutional dif- ferentiation between church and state. In Bâli’s argument, the secular state of the Republic of Turkey, founded in 1923, has actually adapted the former Ottoman state’s practice of managing the religion of a multi-ethnic and multireligious empire. The nineteenth-century Ottoman reformers of the imperial state had continued to make use of religion (that is, Islam, Christianity, Judaism) for family law and communal administration of the population, together with the new nonreligious European laws that strove to unify the empire under a unitary administrative law and codes. In the typical nineteenth-century fashion of monarchial reformism, such as that of the Hapsburg and Romanov empires, which were also multireligious polities, the Ottoman bureaucratic elites and the sultan also set about administering the orders and communities of the multi-ethnic and multireligious empire in multiple ways. In contrast to the earlier centuries of the 700-year-old world empire (it was founded in 1299, according to tradition), the ruling elites made ever more use of the ofcial Sunni Hana sect’s legal interpretation at the state level to align law and educational reforms to a standard. In a greater break with the past, when the religious orders followed tradi- tional customs and genealogies for their leadership, the Ottoman elites began appointing the sheikhs to the Su mystic orders, even subjecting them to state exams. The Ottoman government also tightened controls over the appointment of the religious leaders of the Christian and Jewish communities.

In a similar fashion, the secular republican elites have also used religion, specically Islam, in a more radicalized fashion as the means of homogenization of education and gender to fashion a new citizenry. Turkish reformist elites, since the late years of the Ottoman Empire and during the early decades of the Republic of Turkey, used state power to alter conditions of belief for the population. Therefore, rather than resulting in a plurality of religious perspectives, as Taylor has argued about the North Atlantic world, the result has been a radical secularization of the state with the intent to enlighten and secularize the public while at the same time using “enlightened” Islam to manage the religious component of the social culture.

Bâli’s chapter traces the initial radical measures of the Turkish revolution from the 1920s until the end of the Second World War, which abolished the Caliphate, eliminated religious education and the training of clerics, and founded a secular national education based on the idea of creating a Turkish nation out of the heterogeneous population left over from the demise of the Ottoman Empire. Bâli discusses in detail the emergence of religious discourse in the political history of Turkey after the Second World War, especially with the rst successful multiparty elections of 1950, which brought to power a center-right party elite that began to cultivate the desire for greater religiosity among the Turkish public. These included a new secondary education program, ostensi- bly for training religious imams but in reality to provide a conservative program of education for boys and girls of families who wanted more instruction in religion.

Bâli tends to view these trends as having contributed to the liberalization of republican secular- ism’s staunch principles—for example, ending the ban on wearing religious attire and insignia for civil servants—as part of a general trend to have a new middle class of religiously clad women accepted in the public. But it should be claried that, contrary to popular assumption, the veil was never banned in Turkey. The law on the attire of public servants instructed that female public servants were not allowed to cover their heads while on duty. Though not stated as such, the impli- cation was that religious insignia should not be allowed for public servants, as is the case in France today. The law also prohibited all religious insignia for state employees, such as the yarmulke for Jewish civil servants or visible crosses for Christian ones. (In fact, the republican regulations banned religious attire outside of public duty, allowing the wearing of religious attire only during worship. This included the Muslim turban and the Christian clerical collar as well as the Catholic nun’s veil. All Christian priests and Catholic nuns had to wear secularized versions of their clerical garb in everyday life.)

The laws related to male and female attire during these same early years had also banned the Ottoman male head-covering, the fez, which was not a religious symbol but a dynastic one, for all men. In recent years, the provision that women must keep their heads uncovered has simply been removed from the law, but the laws concerning male dress have not been repealed. So, men are not allowed to wear religious insignia or clothing on their bodies if they are public servants, even though Islam also requires all men to keep their heads covered. Only women have been “lib- erated” to wear a head scarf indicative of their religious persuasion, which shows that the act was not based on a universal principle of liberal expression or personal conviction that the right to religious expression should be gender-free. Rather, the law is based on the liberation of women to dress in Islamic attire as an expression of identity politics whereby only women are designated to uphold “tradition” in dress. To be sure, while not banning the veil from private life, republican elites had made their preference clear by requiring the learning of Western lifestyles by diplomats, civil servants, and even the military, as well as their wives, to symbolize modern Turkey, which had adopted the principle of comprehensive Westernization as the means of modernization. The AKP changes have contested this Westernized image by introducing a hybrid form of the Islamic head- covering together with Western-style modest attire for women that is in step with fashionably dressed conservative Muslim men in Italian suits and ties.

Bâli makes a well-grounded, convincing argument that highlights the strong state monitoring of the religious establishment in Turkey in order to align the general public with the main principles of modernity, including secularization. She also traces the ups and downs of the religious discourse and political currents quite well. The crescendo of the chapter is the discussion of the early millen- nium electoral politics that has brought to power a new conservative party that has been more active in bringing a distinctly religious and Islamic discourse into the public sphere by liberalizing the use of religious headscarf for female civil servants and advocating a stronger religious curricu- lum of secondary education, including banning the consumption of alcohol in state functions and universities. Bâli is correct in noting that the entry of political parties oriented toward political Islam, which emerged rst in the 1960s and 1970s, has not been simply an outcome of the civilian center-right politics and wider democratic participation in the political arena. The military cadres have justied their repeated forced intervention into civilian parliamentary processes—the 1960, 1971, 1980 military coups—in the name of protecting the Kemalist principles of the Republic.

Yet the military governments were the ones that encouraged the foundation of religiously ori- ented parties in order to divide the majority center-right voting constituency of established civilian parties that kept winning elections considered to be undesirable by the military circles. The military regime, especially after 1980, vastly increased the foundation of the Imam Hatip high schools or so-called religious schools. These are vocational schools for the training of religious clerics, such as the imams who conduct the rituals of worship and the hatips, the imams who specialize in giving Friday sermons. The schools were founded in 1948 ostensibly to respond to the wide-spread crit- icism of the republican education program in the early decades after 1923 that largely focused on secular and Western-oriented education without a common core of Islamic subjects as there had been in the Ottoman period. The schools, which have been co-educational from the beginning, have come to function beyond the ofcial vocational purpose, as the preferred secondary schooling for religiously conservative families, who are encouraged to send their children to the schools. (The closest analogy would be Catholic or Evangelical private schools in the United States.) The wider appeal of these schools, which combine the basic Ministry of Education curriculum with courses on the Koran, religious topics, and classical Arabic, is clear from the fact that, according to the Turkish tradition, Muslim women cannot become religious clerics and the schools graduate much larger numbers than is necessary for the profession of clerics serving mosques. The motive of each gov- erning party since 1948 has been to increase the number of religiously oriented high schools in order to respond to the general demand from conservative constituents who preferred these schools because of their religious teaching, and as a means to garner votes from present and future constituents.

But during the coup of 1980, the military rulers exponentially accelerated the founding of these schools, motivated by a strong ideological purpose to educate some youth in Islamic teaching in order to ensure anti-leftist or antiliberal tendencies. The martial law authorities also invented the so-called Turkish Islamic ideological synthesis as a new state ideology that turned the Kemalist vision of secular Turkey into a conservative one, inculcating religious education and Turkish nationalism without a Westernist component. The history textbooks for public secondary educa- tion increased the focus on Islamic history and Turkish history, reducing the strong component of European history and thought that had once been integral to the curriculum. For the rst time in the history of the Republic, public secondary education now included required religious education focusing on Islam, though other religions were briey introduced. In the 1980s the Turkish Islamic Synthesis was claimed to be a citadel against “leftism” and other radical ideologies. One could interpret the post-1980 Islamicization of the Kemalist regimes’ ofcial stance on secular- ism as the military-civilian leadership’s policy of social engineering to create loyal citizens among young people, who would not adopt the radical leftist or ultra-nationalist militant politics that had been mired in street violence and armed conict during the 1970s, leading up to the coup. But these policies at home should also be understood as part of the larger global strategy of American Cold War policy toward Islam, which supported anticommunist, Islamic-oriented nationalist groups in Indonesia, and the training of Islamic guerrilla ghters against the Soviet forces in Afghanistan.6

Most scholars would agree with Bâli’s argument that the rise of multiparty politics in the post- war period also brought forth a grassroots cultural frame. This movement was a result of the wider people’s participation that countered, and in the long run replaced, the historically traditional Istanbul and later Ankara urban educated elite decision-making leadership of Turkey that had pre- vailed since the late Ottoman period. But the complex relationship with Cold War political strat- egies of the day also needs to be taken into account to explain why the Imam Hatip schools gradually became signicant during the twentieth century.

Furthermore, since 2010 the trends have revealed a darker turn that not only compromises sec- ularization and social and cultural secularity but also fertilizes a dominant authoritarianism that makes use of its own version of “Islam” as if it is the ofcial religion of the state, even though legally it is not, and the means to actively inculcate a large constituency of followers through repeated mass meetings. The Religious Affairs Bureau is no longer used actively for homogenization of the whole republican nation; it is instead used for the making of a new religious populace that will support the party in power against political challengers. The so-called kangaroo courts of the last decade that Bâli briey discusses, the Ergenekon and the Sledgehammer, jailed the top com- mand of the Turkish Armed Forces, supposedly for having plotted a coup against the government. After a decade of grueling legal struggle, the court cases have been shown to have been based on doctored evidence. Most of those arrested and jailed have been either found not guilty or released due to lack of evidence, but many ofcers were incarcerated for years without habeas corpus, and some committed suicide in jail.

When the AKP came to power in 2002 through a democratic election, Liberal and Leftist intel- lectuals among the political elites of the European Union and the United States, as well as some in Turkey, considered the social revolution of the election victory as the harbinger of a new Turkey with a “soft” version of the secular republican vision that could possibly be a Muslim model of democracy for the Middle East. Developments since 2002, however, have disproven this optimistic vision. The consolidation of both democracy and an open society in Turkey, which began with the liberal economic reforms of the 1990s and accelerated in the early 2000s, escalated and then reversed with the sudden eruption of a major conict between the two religious factions of the AKP: the so-called national view faction of those in government versus the followers of Fethullah Gülen, a popular preacher who has led a new religious movement since the late 1970s appealing to the rising middle-class aspirations of the country.7

Having entered into the AKP party in the early 2000s, the Gülenists, who were mostly better educated, having graduated from Turkey’s secular schools and colleges and universities in the United States, were accorded a special entry into the state ministries and other institutions. The showdown with the national view faction and subsequent coup attempt by a faction of the Turkish military on July 15, 2016, led to the expulsion of Gülenist Muslims from the AKP and the government, and to emergency measures such as purging more than 100,000 people from pub- lic service without any legal precedent and the arrest of hundreds of thousands more, some of whom had private property and assets expropriated by the government.8 The government has also curtailed academic freedoms by tightening control over universities and other institutions.

I return to Tekin’s argument about constitutionalism and people’s democracy in order to show how the AKP’s experiment with Muslim democracy has diminished the prospects for a democratic regime of multiculturalism or multiplicity of lifestyles that was supposed to enrich Turkey through a generous reinterpretation of secularism for the Republic. Tekin is one of those thousands of academics purged from universities since 2016 in the wake of the violent military upheaval of July 15. The ruling party’s response to the attempted coup has made previous claims of populist religious support for a civilian liberal democracy or a higher moral ground over secular political discourse quite unconvincing. In fact, the 2019 local elections across the country that brought opposition coalition candidates to power, among them the striking victory over the AKP in Istanbul, have shown that religiously pious discourse alone is no longer satisfying the desires of the general public.

The recent events have also made it clear that the enlargement of popular religious politics, though initially celebrated as a challenge to top-down secular elitism, does not guarantee the strengthening of a liberal, secular, and democratic society. In fact, one can argue that popular reli- gious politics can also be kindred to populist national socialist tendencies as religion plays a con- venient role in activating mass politics. Furthermore, the presence of a strongly religious Islam-oriented politics through the electoral process has not made Turkey’s public culture more het- erogeneous. Rather, the popularly elected conservative political leadership in local and general elec- tions has used its power to impose Islamic practices in the public sphere from the beginning, including the immediate ban on selling alcohol in municipal and state restaurants in 2002, which should have been a telltale sign of what lay ahead. Serving wine, beer, or raki in municipal restaurants open to everyone had been a common practice in Istanbul for almost a century, but res- taurants in downtown areas of cities have found it very difcult to get liquor licenses or to have old ones renewed. The government has also prohibited the serving of alcohol in any public function; encouraged gender separation in social gatherings; and allocated vast public funds to religious sec- ondary education, as discussed above, to compete with the secular schools. Therefore, at this point it is difcult to view the entry of Islamic discourse and practices in a more overt manner especially in the big cities as a fact in itself that will guarantee the multiple social lifestyles envisioned for liberal secularism that is in line with Taylor’s argument for Secularity III.

Finally, it should be noted that Bâli’s chapter, though informative, does not deal with the reality that Turkish society also has a major Alevi population—20 percent of the general population—that brings a religious and cultural dimension to secular politics. The Alevis, who are connected to the non-Sunni religious orders, some of which are related to the Shiite sect, are mostly Turkish and include a small (15 percent) Kurdish minority. The Alevis have tended, traditionally, to support the republican reforms and have voted more along social democrat lines since the 1970s. Most Kurds, who are roughly 15 percent of the general population, are religiously conservative and have been supportive of the conservative political parties. Ethnicity and religion do not conate in the region. A small minority of Kurds have been supportive of Kurdish rights, though the move- ment has also been supported by opposition parties and urban liberal groups. But their public image has been marred due to their connections with the terrorist Partîya Karkerên Kurdistanê, or PKK (Kurdistan Worker’s Party), an organization of some radical Kurdish networks. During the early decades of the Republic, the Alevis initially chose to support secularism because they had customs and beliefs that were not in line with state-sponsored Islam, and they believed that sec- ularism would protect them from the Sunni prejudices that had traditionally prevailed among the Anatolian population.

Bâli’s chapter does not address the Alevi presence, nor does it deal with the conditions and reli- gious and social lifestyles of the Christian and Jewish minority populations of Istanbul. While the contestation between Muslims and secularists is the dominant narrative of Turkey’s history of sec- ularization and religion, the treatment of non-Muslims, even though they are few in number, serves as a litmus test of whether secularism and religious tolerance is truly working in Turkey’s venture into secularity. In Turkey, there are 20,000 Jews; 50,000 Armenian Christians; and 3,000 Greek Orthodox Christians, along with some other small Christian groups, such as the Anatolian Syriac Christians. The conservative Muslim politics of recent years has brought an overtly anti-Semitic and anti-Christian tinge to public discourse, even while vigorously arguing for the rights of covered Muslim women. The non-Muslim population’s attitudes toward republican secu- larism has also been traditionally positive as a protection from Islamic conservatism, but the non-Muslims have greatly suffered in periods when nationalist hegemonic discourse and practice have discriminated against non-Muslim communities. Turkish Greeks greatly suffered during the Cyprus crisis and many were forced into exile. Turkish Armenians have endured silently during the eruption of Armenian terror and subsequent genocide debates. While Turkish Jews have moved in republican circles in the past, the rise of anti-Israeli and anti-Semitic discourse among the AKP circles has become very pronounced. During the last two decades, Jewish synagogues have been bombed and Jewish businessmen have been assassinated. It would be difcult to say that the ruling religiously conservative Muslims have been particularly liberal in accepting and showing “tolerance” toward the lifestyles of non-Muslims. This is particularly true in view of the perennial legal problems that these communities face in defending their religious foundation property from conscation or in the lack of legal resolution in the 2007 assassination of Hrant Dink, the major voice of Armenian and Turkish friendship. In these events, the AKP continued to be seen as a civil- ian democratic force, particularly among liberal progressive secularists in Turkey and internationally.

On a lighter note, as in many global cities, Western-style New Year’s decorations and lights have been assimilated into the urban culture of Turkey’s cities, especially metropolitan Istanbul for many generations. During recent New Year’s seasons, the Religious Affairs Bureau somberly and repeat- edly declared that celebrating New Year is a Christian practice that devout Muslims should avoid. The somber announcement has become so predictable that it has become the topic of Istanbul jokes. Press columnists merrily predict that the religious injunction against New Year’s celebrations is part of the season’s festivities just as much as Santa Claus, known as “Noel Baba” in Turkish. More ominous, however, are groups of angry young men who roam around the city shouting rad- ical slogans, proclaiming that the New Year’s celebrations and Christmas tree decorations of down- town Istanbul are evil. Part of the social reaction against New Year’s celebrations that has assimilated the Christmas tree as the “New Year’s Tree” for generations in Turkey is that the vast population from the poor squatters’ neighborhoods in Istanbul, which include many voters for the ruling conservative party, have encountered a city culture that is alien to their customs. Istanbul Muslims have traditionally participated in the celebration of Christmas. The city has an ancient Ottoman tradition of Muslims who stand at the back of churches on Christmas Eve, quietly reading the Koran, with women who piously cover their heads as they would in a mosque.

Time will tell whether the rise of religious views in social and political spheres will encourage liberal secularism in Turkey. It is ironic to note that despite a decade of vicious “bad press” within religiously conservative circles, including the 2016 claim in a fringe journal that Atatürk was a “blue eyed devil” and his mother a prostitute, and that the Republic was the doing of two drunks (Atatürk, who liked his raki, and his successor in ofce, Ismet Inonu, who was actually a teetotaler), recently Atatürk’s image has gained a remarkable popularity among the general population, espe- cially the young. Even some conservative journalists, such as Ahmet Hakan of Hurriyet, a popular mainstream paper, have confessed that they have come around to appreciate his secular revolution because of the dangerous jihadist terrorist acts of ISIS that have spilled into Turkey. For all the crit- icism of republican elitism and authoritarian practices in the early decades of the Republic, it looks as if the public will turn to a new Kemalism of the second millennium for constructing Secularism III rather than to the multi-institutional religious groups who, despite having enjoyed more than two decades of popular power, have failed to carry religious coexistence with secularity to a plu- ralistic level beyond having some conservatively clad women gain employment with the right to wear a headscarf to public ofce. In view of the checkered legacy of Islamic politics and social life in recent years, it appears unlikely that the religious communities themselves will help generate a multi-institutional and multi-“cultural” liberal secularism. One has also to remember that there is a dynamic interregional interaction among some communities, organizations, and networks, though they might be small in numbers, that in the name of Islam have a propensity toward the radical politics of groups such as Al-Qaeda or the savagery of the Syrian ISIS Caliphate terrorist organization. Most of the Muslim polities of global Islam in the Middle East exhibit either extremely doctrinal fundamentalism, such as in Saudi Arabia; religious state doctrine, such as in the Islamic Republic of Iran; or some form of politically radicalized Islamic religion, such as among the factions in the Libyan civil war. Any assessment of Turkey’s venture into secularism that does not take into account the existence of strong Muslim global and transnational networks is bound to be quite incomplete.

I end with the observation that the history of secularism in Turkey reveals the complex internal and external factors that have been embedded in the process. The prospects for a conservative Muslim democracy probably have to wait for another attempt in the future. »

Selçuk Esenbel

Emeritus Professor, Boğaziçi University

notes:

1 For further discussion of Taylor’s Secularity III framework, and how it is engaged in this book, see André Laliberté, “How Do We Measure Secularity?,” Journal of Law and Religion 36, no. 2 (2021) (this issue), and Clemens Six, “Transnational Perspectives on a Global Secular Age,” Journal of Law and Religion 36, no. 2 (2021) (this issue).

2 Serdar Tekin, Founding Acts: Constitutional Origins in a Democratic Age (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 1–16. In this introductory discussion, Tekin addresses how, historically, the hegemonic vision of a unied people has been frequently imposed on diverse populations by elites and argues that the foundational prin- ciple of popular sovereignty must be performatively present with people participating in the founding act of creating the constitution. He goes on to discuss Rousseau’s lawgiver as architect, who Rousseau sees as inevitably necessary at the moment of the founding act after a revolution to provide the legal frame to a people not yet living under conditions of a democratic order. Rousseau’s expectations of the elite role in the founding of constitutions have been criticized as democratically decient and even an authoritarian strain in his thought that ignored the agency of the people. Tekin partially rescues Rousseau’s lawgiver by recasting it as an interpreter who produces legislation that reects the moeurs of the people. Even accepting that it is possible, following Tekin, to recast the lawgiver as more democratically informed, Turkey’s republican revolution, with its Kemalist vision of staunch secularism and westernism, was in line with the lawgiver as architect ignoring the agency of the people for the sake of their sov- ereignty. Although there is not enough space here to pursue this engaging analogy, it is worth noting that the gov- erning party’s recent populist critiques of republicanism and dismantling of republican institutions and ideals probably reects the deeply felt resentment among people over the lack of popular participation in the making of the republican moment. This angry reaction was well illustrated by the sudden reversion of St. Sophia into a mos- que in 2020 after sixty-ve years as a museum that represented the Byzantine and Ottoman legacy, as well as the new republic’s discreet message to the Western world in 1934 about the end of religious conict between Islam and Christianity.

3 For further studies of secularism in Turkey, see the following: Niyazi Berkes, The Development of Secularism in Turkey (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1964) (the seminal work on the subject to date and based on the pre- sumption of secularism as progressive modernity and an analysis of Turkey’s historical challenge); Ahmet T. Kuru, Secularism and State Policies toward Religion: The United States, France, and Turkey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Murat Akan, The Politics of Secularism: Religion, Diversity, and Institutional Change in France and Turkey (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017) (relatively recent comparative studies); Zafer Toprak, Atatürk: Kurucu Felsefenin Evrimi [Atatürk: The evolution of the founding philosophy] (Istanbul: Iṡ ̧ Bankasi Kültür Yayınları, 2020) (the best intellectual history of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s foundational philoso-

phy, which was strongly inuenced by Jean Jacques Rousseau and other thinkers of the French Enlightenment).

4 Tekin, Founding Acts, 147, quoting Avishai Margalit, Ethics of Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press, 2009), ix.

5 MehmetAcet,“BizimHikayeMi,BasķalarınınHikayesiMi?”[Isthisourstory?Orthestoryofothers?],

YeniŞafak, August 15, 2020, https://www.yenisafak.com/yazarlar/mehmetacet/bizim-hikaye-mi-baskalarinin- hikayesi-mi-2055949. Acet’s column supports the recent statement of Dr. Ibrahim Kalin, the leading advisor to President Erdogan, that we have been living under the fairy tales of others’ modernity for the last 150 years, and it is time that we create our own fairy tales. The statement provoked wide criticism for its rejection of the centuries-long history of Westernization in the Ottoman period and the Republic.

7 The Gülenists are somewhat similar to new religious movements elsewhere, such as the Soka Gakkai of Japan or the followers of Dr. Sun Myung Moon’s Unication Church, which was at one point quite popular in East Asia and in the United States. For a recent critique in the aftermath of the 2016 coup attempt, listen to a recording of a round- table discussion with academics David Tittensor and Tezcan Gümüs:̧ Ali Moore, “The Rise, Fall and Future of Turkey’s Gülen Movement” (podcast) Jakarta Post, October 31, 2019, https://www.thejakartapost.com/multime- dia/2019/10/14/the-rise-fall-and-future-of-turkey-s-gulen-movement.html. For a relatively positive view that was quite prevalent earlier, see M. Hakan Yavuz, Toward an Islamic Enlightenment: The Gülen Movement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Richard Seagar, Encountering the Dharma: Daisaku Ikeda, the Soka Gakkai, and the Globalization of Buddhist Humanism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

8 Amnesty International reported the following in relation to the events of July 15, 2016:

More than 115,000 of the 129,411 public sector workers—including academics, soldiers, police ofcers, teach- ers, and doctors—arbitrarily dismissed by emergency decree following the 2016 coup attempt remained barred from working in the public sector and were denied passports. Many workers and their families have experi- enced destitution as well as tremendous social stigma, having been listed in the executive decrees as having links to “terrorist orgarizations”. A commission of inquiry set up to review their appeals before they could seek judicial review, assessed 98,300 of the 126,300 applications it received and rejected 88,700 of them.

A law adopted in 2018 (Law No. 7145) that allows dismissal from public service to be extended for a fur- ther three years on the same vague grounds of alleged links to “terrorist organizations” was used by the Council of Judges and Prosecutors to dismiss at least 16 judges and 7 prosecutors during the year, further undermining the independence and integrity of the judicial system.

Amnesty International, Human Rights in Europe—Review of 2019—Turkey EUR 01/2098/2020, reprinted at, https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2028219.html (original source no longer available).