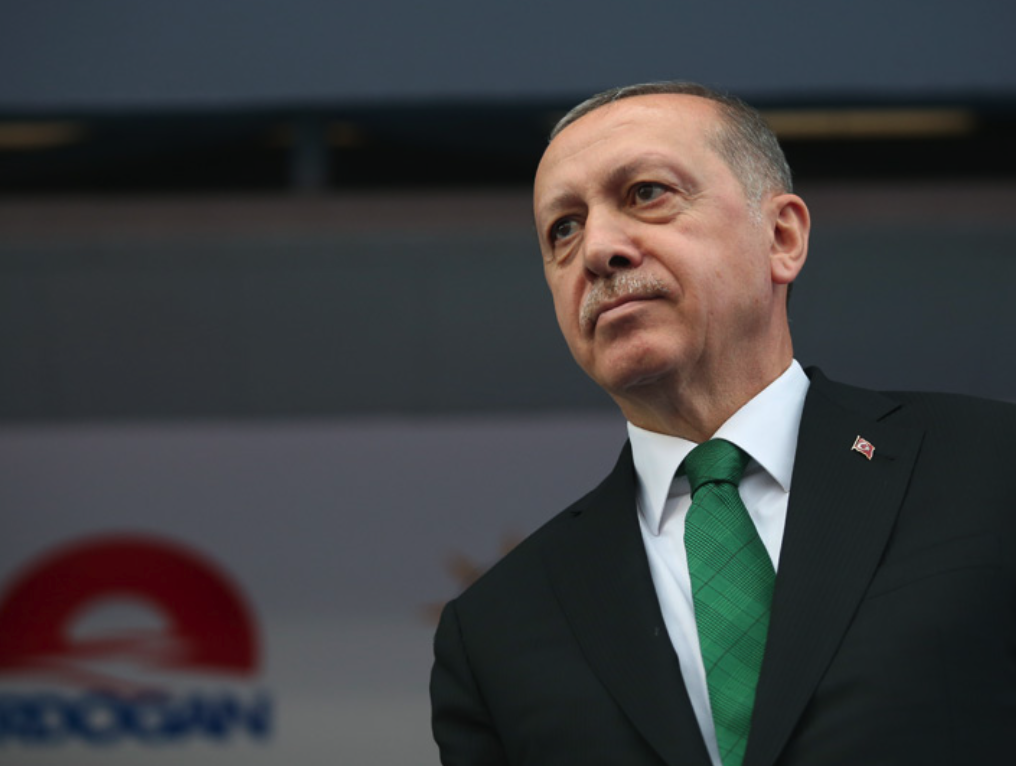

Erdogan has two priorities: to chart a more assertive presence for Turkey and to leverage Ankara’s position inside Western institutions to make that happen. By Sinan Ciddi in Foreign Policy on June 8, 2023.

Since Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan secured his third term on May 28, the shock of his decisive defeat of the opposition has largely given way to questions about what Erdogan’s new term will mean for Turkey—especially its foreign policy.

Erdogan now has two priorities: to chart a more assertive presence for Turkey globally—one that is not beholden to the policy prerogatives of its traditional Western anchor, the United States—and to leverage Ankara’s position inside Western institutions such as NATO and the European Union to service his first goal.

To achieve both, he will continue to primarily highlight his ever-deepening ties with President Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Erdogan will emphasize Turkey’s fundamental importance to the West by underlining the vital role that Ankara plays in helping to contain Russia in Ukraine, mainly through weapons sales. Since the beginning of the conflict, Ankara has sold Turkish-made TB2 drones to Kyiv; it also brokered a grain shipment deal with Russia, facilitating the sale of Ukrainian grain to world markets and likely averting a world food crisis.

Moreover, increasing tension in the Balkans, with renewed Serbian aggression in Kosovo, already has Ankara stating its willingness to play a key role in reinforcing stability. Erdogan will also continue to impress upon the European Union that Turkey will remain a bulwark against migratory and refugee flows to Europe.

In return, he will demand respect from Europe in the form of no criticism for Turkey’s lack of democratic governance at home while exploring opportunities to upgrade Turkey’s existing access to European markets and visa-free travel to the Schengen Area for Turkish citizens. If you think that Erdogan is reaching, you are mistaken. Europe stands ready and largely grateful for Erdogan’s continuity. The European Union poured platitudes upon him following his election victory and are salivating at the opportunity to please Erdogan, all for the sake of preventing migration to the European heartland.

The picture from Washington is much the same. The Biden administration is keen to maintain a cordial relationship with Ankara. Turkey wants to acquire new F-16 fighter planes for its aging air force. Its demands basically stop there, though, and Ankara is not interested in rebuilding substantive ties with Washington. President Joe Biden is seeking to accommodate Erdogan for two reasons: Transactionally, if Erdogan agrees to ratify Sweden’s pending accession to NATO, it will be seen as a win for the Biden administration and NATO. Additionally, the White House does not want Turkey to completely fall under Putin’s influence. Turkey has to acquire jets from somewhere; it might as well be the West.

All eyes are now on Erdogan to see if he will finally greenlight Sweden’s NATO membership at the alliance’s July summit in Vilnius, Lithuania. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg attended Erdogan’s inauguration ceremony to court Turkey’s approval. Biden and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken preceded Stoltenberg by vocally urging Erdogan to approve the accession as soon as possible while congratulating Erdogan for his election victory.

Yet worries continue that Erdogan could draw this out further. Turkey recently demanded that the Swedish government take action against Kurdish demonstrators who protested Erdogan’s reelection by projecting an image of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) flag on the face of the Swedish parliament building. Ultimately, though, Turkey is likely to ratify Sweden’s accession simply because that is the only way that Ankara will be able to get lawmakers in Washington to approve F-16 sales.

In all these calculations, both Brussels and Washington seek to achieve a number of individual policy goals. But Erdogan is the net winner. He sets the tone of the relationship and the agenda with the West. He does not want a fundamental reset or reimagining of ties. To the West’s chagrin, Erdogan will continue to assert his regional influence.

His ability to do so, however, will largely rest on the degree to which he can end Turkey’s military presence in Syria and rebuild ties with regional powers. In the latter case, Erdogan already initiated a rapprochement with Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Israel—all in 2022. He will need to build on these relationships, as he will have to rely on these powers to continue depositing hard currency in Turkey’s cash-strapped central bank and invest in Turkey’s economy.

Erdogan will not go knocking on the door of the International Monetary Fund to stabilize his country’s economy. Doing so would mean opening up the books of the country’s government spending, which he cannot do, as it’s riddled with corruption. He can, however, approach regional powers and entice them to invest in Turkey, mainly by selling off key assets of Turkey’s sovereign wealth fund.

In Syria, Erdogan will need to lean on Putin. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whom Erdogan spent a decade trying to overthrow, is in no mood to please Erdogan. Yet Assad is beholden to Putin, who wants an end to Syria’s civil war. While Erdogan will be keen to repatriate a sizable number of Syrian refugees, which he can sell as a win to voters at home, what will Assad want in return? All Turkish troops out of Syria.

This is one area where Erdogan’s new foreign minister, Hakan Fidan, could prove useful. As the former head of Turkey’s National Intelligence Service (MIT), Fidan attended all of the high-level meetings with the Syrian government in 2022 that were intended to normalize relations. That said, we know relatively little about Fidan. He has not given any public interviews in his career and always kept a low profile in his service to Erdogan.

Fidan played a pivotal role in overseeing the peace talks with the PKK in the early 2010s, and he is not necessarily interested in anchoring Turkey firmly in the West again. His previous appointment to the MIT was criticized by Israel’s then-defense minister, Ehud Barak, who accused Fidan of having close ties to Iran. Though that accusation has not been substantiated, Fidan’s appointment as foreign minister could be negatively interpreted by the Israeli government, with which Turkey is attempting to strengthen ties.

Regardless of his worldview, Fidan likely shares Erdogan’s priorities, and he is a good foot soldier. In comparison to his predecessor, Mevlut Cavusoglu, Fidan is also measured and purposeful.

Yet Erdogan will continue to run Turkey’s foreign policy as he sees fit. Since 2017, Erdogan has centralized power and decision-making into a new presidential government system that pushed out the parliamentary system promulgated by Kemal Ataturk in the 1920s. Although there is a cabinet, the ministers that occupy traditional positions such as interior and foreign minister hold no political responsibility for the decisions. As unelected appointees of an elected president, they are largely there to implement the decisions that Erdogan decrees.

Take, for example, Cavusoglu. Throughout his tenure, he was little more than a messenger for Erdogan. The decision to acquire the S-400 missile defense system from Russia, which deeply poisoned the U.S.-Turkish relationship, was not a consultative one, derived with the input of Cavusoglu, the Foreign Ministry, and the wider Ankara security establishment. Erdogan insisted on the purchase, which under a system of institutional decision-making would have been strongly resisted by the military, the National Security Council, and the Foreign Ministry.

Put simply, as Erdogan desires, his minions do. It may just be the case that Fidan will be able to sell his message better.

Sinan Ciddi, is an associate professor of national security studies at Marine Corps University and a nonresident senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.