Erdogan has few role models for how to peacefully concede power. By Reuben Silverman in Foreign Policy on April 22, 2023.

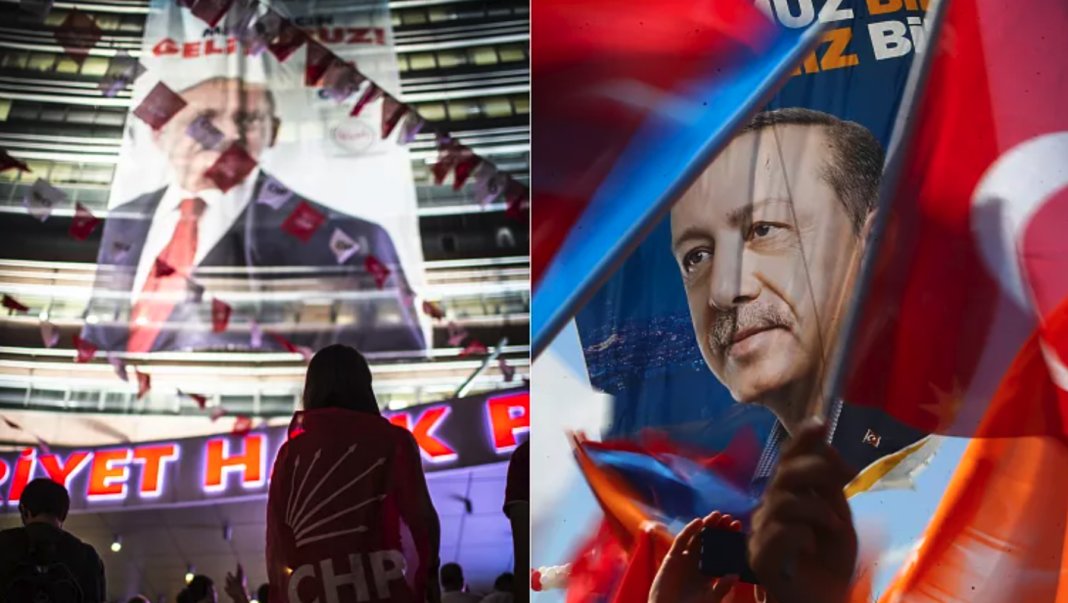

Turkey holds presidential and parliamentary elections on May 14. They could unseat President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), who have governed for the past 20 years. In that time, Erdogan and the AKP have left a deep mark on the country—expanding the role of Islam in the traditionally secular state and growing Turkey’s influence abroad. But years of unorthodox economic policy and a deadly February earthquake have undermined confidence in the government, leading many voters to question the reputation for competent administration that has traditionally been central to the AKP’s appeal.

After two decades, Erdogan’s departure is hard to imagine. Polls suggest that he may be defeated by an opposition candidate, but there is widespread belief that he will do whatever it takes to stay in power, using his incumbency advantages to eke out a narrow victory or challenge unfavorable results.

Much of the anxiety surrounding Turkey’s presidential contest—and how Erdogan will respond to its results—is a consequence of his unique position in Turkish political history. It is hard to imagine Erdogan gracefully accepting defeat because it would be unprecedented: No Turkish president has ever been directly voted out of office.

Not only is Erdogan the first Turkish president to be popularly elected rather than chosen by parliament, but he has also overseen the country’s transformation from a parliamentary to a presidential system. While many of Erdogan’s 11 appointed predecessors came and went without a fuss, the few who—like him—were backed by a mass political party tended to remain in office until they were removed by the military or faced an unexpected death. And the lone exception is not encouraging.

Turkey’s founder and first president, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, died in office at the relatively young age of 57, likely due to his hard-partying lifestyle. His successor and close confidant, Ismet Inonu, served 12 years, until the Republican People’s Party (CHP)—which he and Ataturk led—was defeated by a breakaway faction called the Democrat Party in 1950 in Turkey’s first relatively free and fair elections. The Democrats criticized the overbearing, secular state and praised private enterprise, and have been held up by politicians like Erdogan as demonstrating the natural link between center-right politics and democracy in Turkey. Erdogan’s decision to hold elections on May 14, the anniversary of the Democrats’ victory over the CHP, is meant to emphasize this connection.

Inonu, already 65 years old in 1950, accepted his party’s resounding defeat but chose not to retire from politics. He continued to lead the CHP for another 22 years until he was finally forced out at a dramatic 1972 party convention by Bulent Ecevit, who had spent nearly a decade as the older man’s successor-in-waiting. Inonu died a year and a half later. Though he never became president, Ecevit would remain a major figure in politics for three more decades, leading the CHP until it was banned following a military coup in 1980. Later, he would head a successor party loyal to him.

The Democrats’ leader, Celal Bayar, served as president for a decade until he was removed by a military coup in 1960. In its aftermath, he was sentenced to death along with several government ministers. However, coup leaders commuted the sentence due to his advanced age. Bayar and many of the surviving Democrats spent much of the next five years in prison. (The joke was on the military: Bayar lived to be 103 and continued influencing politics behind the scenes for many years after his release.) Those Democrats not in prison during the early 1960s formed the new Justice Party, led by Suleyman Demirel. Demirel proved to be a wily politician and would maintain control over the party and its successors for almost four decades.

Parliamentary elections in the 1960s and 1970s were fought between a center-right faction led by Demirel and a center-left group championed by Ecevit. At the presidential level, however, the military remained in control. The constitution adopted following the 1960 coup stated that presidents must be elected by parliament to a single seven-year term; consecutive terms in office were prohibited. The three presidents of this era—Cemal Gursel, Cevdet Sunay, and Fahri Koruturk—were former generals or admirals. The inability of clashing political factions in parliament to select a new president at the end of Koruturk’s term in 1980 was among the many factors that encouraged the military to launch a fresh coup that year, dissolving parliament, writing a new constitution, and tapping yet another general, Kenan Evren, as Turkey’s seventh president.

The military regime disbanded the CHP and Justice Party. It also banned both Demirel and Ecevit from politics. In theory, this could have allowed new faces to emerge on the Turkish scene, but Demirel, Ecevit, and other politicians regained their political rights in a 1987 referendum. During their absence, the center-left was held together by Inonu’s son Erdal, who lacked Ecevit’s charisma, and the center-right became dominated by the Motherland Party, led by Demirel’s longtime friend Turgut Ozal, whose victory over military-supported parties in the first post-coup elections in 1983 came as a rebuke to the generals. When Evren retired in 1989, Ozal become Turkey’s first civilian president since 1960.

When Demirel reentered politics, he was not pleased that his former ally Ozal now dominated the political scene, so Demirel competed in elections under the banner of his own True Path Party. In 1991, the Motherland Party lost control of parliament to a coalition led by Demirel. When Ozal died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1993, before his term had ended, Demirel was able to secure the presidency for himself. But by the time Demirel’s term concluded in 2000, he could not pursue a second term; doing so would require a constitutional amendment and political support that he lacked. His party was deeply unpopular, and his old rival Ecevit was now prime minister. Demirel was succeeded by the president of the Constitutional Court, Ahmet Necdet Sezer, who was acceptable to most political factions—except politicians representing Islamist and Kurdish interests, which were both under pressure from the judiciary.

It was a shared alienation from the secular, nationalist state—which Sezer championed—that led many religious and Kurdish voters to support Erdogan and his newly formed AKP in the 2002 parliamentary elections. Erdogan had been mayor of Istanbul and a member of the Islamist Welfare Party until it was banned and he was removed from office in 1998. His outsider status allowed him to benefit as corruption scandals and a devastating earthquake sapped voters’ confidence in the established political elite. The parties associated with Ecevit, Demirel, and Ozal were utterly defeated at the polls, and only two parties—the AKP and a reconstituted CHP—managed to enter parliament. None of the parties that had voted Sezer into office two years earlier remained in the body when Erdogan was inaugurated as prime minister in 2003.

Sezer initially proved to be the main obstacle to Erdogan and the AKP’s exercise of authority, repeatedly vetoing bills and blocking nominees for key positions. When Sezer’s term ended in 2007, the AKP replaced him with one of its own, Abdullah Gul. With Gul in office, the AKP was able to consolidate power over the bureaucracy and judiciary. Yet power became concentrated with Erdogan and his close allies rather than with Gul. In one notable instance, when the head of the Turkish Bar Association gave a speech criticizing the government, Erdogan stormed out of the room with the president trailing behind him. It came as no surprise when Erdogan himself chose to run for president in Turkey’s first direct presidential elections in 2014 and Gul stood aside without a fight.

Erdogan has transformed the office of the presidency. During his first term—when the role required him to cut ties with his party—he frequently intervened in government decision-making and acted in a partisan manner that many legal experts believed to be prohibited. A 2017 referendum backed by Erdogan approved constitutional changes that eliminated the office of prime minister and turned Turkey into a presidential system that Erdogan argued would ensure more effective governance. During his second term, Erdogan has used his newfound authority to meddle in the few sectors of society that remained somewhat autonomous, cycling through four central bank presidents in as many years.

Turkish presidents installed after coups or backed by the military were able to bend institutions to their will, but they lacked political parties to connect with the public. Presidents who led political parties, meanwhile, enjoyed popular support but never wielded such direct influence over all state institutions. Erdogan is unique in that he has both state control and a sizable following that does not want to see him give up power. If he loses next month’s elections, it will likely be by a narrow margin. And, at 69 years old, he would be relatively young compared to past Turkish leaders at the ends of their careers. In short: Erdogan has few models for how to peacefully relinquish power.

The only Turkish president who voluntarily left office while still wielding power and influence comparable to Erdogan’s was Inonu in 1950. This transition proved to be rocky: The Democrat Party and its supporters deeply resented Inonu and the CHP; in the years that followed, the victorious Democrats seized CHP property, prosecuted one of Inonu’s sons for vehicular homicide on flimsy grounds, and even removed a hearing aid from Inonu’s box at the state opera. The Democrats also organized gangs of supporters to attack Inonu’s rallies. The 1960 military coup that removed the Democrats from power came as it seemed the party was preparing to shutter the CHP.

Erdogan seems to like to identify with the Democrats and the mistreatment they received from the military. Yet it may be the memory of how the Democrats treated Inonu and other defeated opponents that has raised the stakes of losing in Erdogan’s mind. The current Turkish opposition frequently accuses him of being a corrupt dictator, which holds out the possibility that he or his family might face prosecution once out of office. Erdogan clearly takes these accusations seriously: Opposition leaders have been fined and prosecuted for their statements.

To ease Erdogan’s fears of a loss and all that it might entail, Turkey’s opposition parties would do well to avoid denunciations of the president and craft a positive message that explains to voters the positive steps they will take once in power. This was part of the CHP’s strategy in its successful 2019 Istanbul mayoral campaign.

Erdogan’s main challenger, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu, made a name for himself as a critic of AKP malfeasance. Since his nomination he has mixed a positive agenda with promises to end corruption. He has focused on pocketbook issues and social welfare while emphasizing that he will end the flow of money to a powerful clique of pro-AKP companies. He has contrasted the divisiveness of Erdogan’s “one-man” regime with the inclusiveness of the opposition coalition, which is CHP-led but contains ideologically diverse parties all intent on removing Erdogan from office. Whether this balancing act can excite voters without hardening Erdogan’s resolve to hold onto power remains to be seen.

Kilicdaroglu’s broad coalition is necessary because no dominant Turkish political personality has emerged to rival Erdogan; there is no Ecevit to his Demirel, or Inonu to his Bayar. In part, this is Erdogan’s own doing: Exciting politicians like Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu and Selahattin Demirtas, leader of the Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party, have been sidelined by prosecutions and imprisonment. For Erdogan, being the first to achieve this much power has required vision and imagination. The question is whether he can also imagine being the first to relinquish it.

Reuben Silverman is a researcher at Stockholm University’s Institute for Turkish Studies.