In his first interview since he was released from prison, Turkish writer Ahmet Altan has told people to speak up and not be afraid. « You can’t make fear so ordinary. Fear is so ordinary now, and I don’t think it’s something we can accept so easily…I went to prison, I came out, and I can go back again, » he said.

In his first interview since being released from prison, writer Ahmet Altan spoke with Yasemin Congar for Kıraathane Literature House’s YouTube channelabout his four-and-a-half years behind bars.

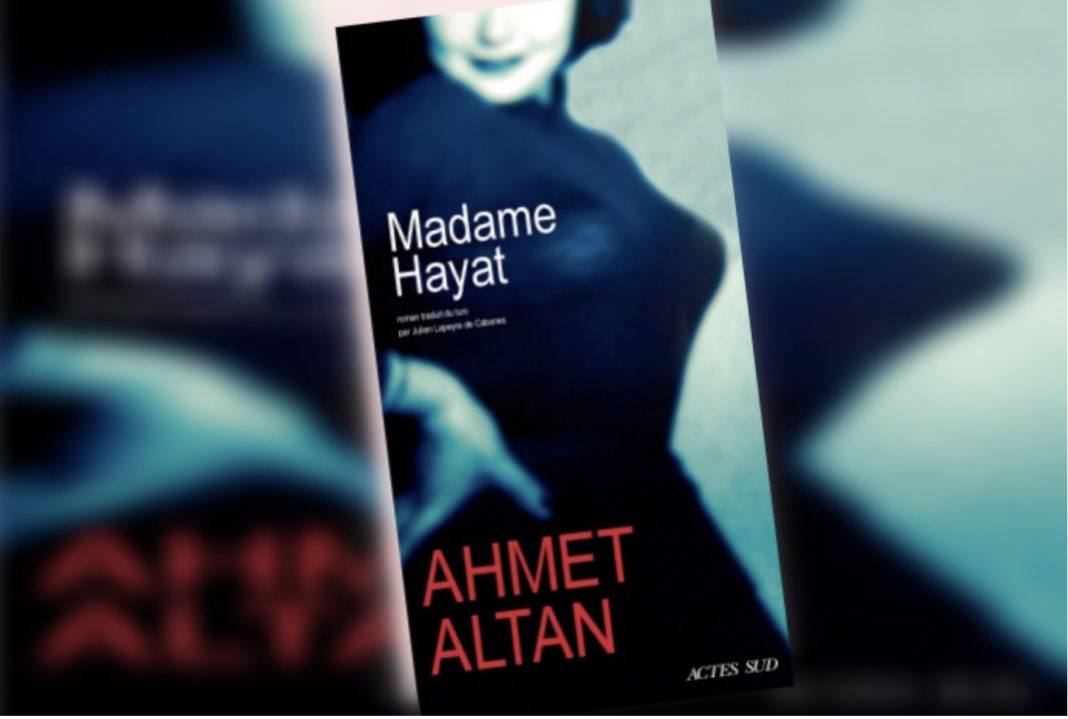

He encouraged the Turkish populace to retain hope and not be afraid. He also discussed the three books he wrote while held on an aggravated life sentence in Silivri Prison – “I Will Never See the World Again,” “Lady Life,” and “Dice”– none of which were published in Turkey.

Altan emphasized to Congar that this was not his choice, that he wants Turkish readers to be able to read these books.

“Every author wants his book to be published in the language in which it was written,” he said, “This is my country. If it is not published, [that choice] does not come from the author.”

Ahmet Altan and his brother Mehmet were arrested in a dawn raid on September 10, 2016, following the coup attempt of July 15, 2016. Both brothers were convicted in February 2018, alongside journalist Nazlı Ilıcak, for “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order. » They were handed aggravated life sentences.

In July 2019, an appeals court cleared both brothers of their life sentences. Mehmet Altan was released. However, Ahmet Altan remained in prison on charges that he was aware of the July 15th coup’s planning.

He was sentenced to 10.5 years in prison in November 2019, but was provisionally released for having already served three years in prison. A prosecutor immediately appealed the decision, however, and he was rearrested shortly thereafter. Finally, on April 14, 2021, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Ahmet Altan’s imprisonment violated his right to freedom of expression. He was released from prison the next day.

Despite his four-and-a-half year imprisonment, Altan in the Kıraathane interview told Congar he was in good health. He told listeners they should not fear prison, that that fear causes people to self sensor and contain their actions.

“I am really well. My health is good, my morale is good, I took care of myself in prison,” he said, “If you walk in your yard, if you do sports, it’s not that scary. It’s not a threat that should cause you to lock up your whole life, to give up your personality and dignity to this fear.”

He also touched on the common saying, “Silivri is cold” (Silivri soğuk), meant to warn of the severe punishment political dissidents can face in Silivri prison.

“There is this saying, ‘Silivri is cold.’ Let me tell you, Silivri isn’t cold. It’s not. The heaters work wonderfully and the food isn’t bad at all,” Altan said.

He encouraged listeners to not succumb to their fear, to do more than just complain about Turkey’s current condition. Conditions are bad, he said, but one can speak up, one can write.

“Go and complain as much as you want. You can’t change the conditions, but there are things you can change, like your own behavior. You can talk, you can write, you can say something. You can’t make fear so ordinary. Fear is so ordinary now, and I don’t think it’s something we can accept so easily…I went to prison, I came out, and I can go back again.”

Society needs people who are not afraid, he said. People need to live truthfully without fearing punishment or imprisonment – he himself does not fear being imprisoned again.

“Don’t be afraid. Why are you afraid? It’s nothing to be afraid of. I went in, I slept, I got out. I went in again, I slept, and I got out. I will go in again, I will sleep, and I will get out.”

Altan in the interview also discussed the books he wrote in prison, particularly “Lady Life” (Hayat Hanım), which focuses on the relationship between a young literature student who works as an extra on a television show and the leading lady, Hayat Hanım.

Altan said that were he not to have gone to prison, he would have never been able to write the book – there, he was introduced to FlashTV on the TV in his cell, where all the women “wear extraordinarily low-cut clothes and play games.” The world of “Lady Life” was devised from hours of watching these television shows.

Altan posed a question to Turkish writers, and others in countries where their freedom of expression is challenged. Writing gives you the opportunity to raise your voice he said, but writers must choose whether they are willing to accept the consequences of doing so.

“There is a contradiction in writers’ lives in countries like ours,” he said, “You have a pen in your hand and you have the ability to raise your voice. People are in pain. People are being tortured, they are hungry, they are dying in the streets, they are being persecuted, they are being imprisoned unjustly. Will you write to help them? If you do, you will lose time and potentially some parts of your life. Or will you say, ‘These are ephemeral parts of life, literature is permanent,’ turn your back to all of this, and only write novels and essays for the rest of your life? This is a very serious question.”

Duvar English, September 9, 2021, image: TR724