A narrowing space for reliable media has encouraged alternative platforms that promote hateful language, bigotry, and racism directed toward Syrians. By Sude Akgundogdu in Washington Institute on March 20, 2023.

For a version of this essay with sources, download the PDF.

In early February, two major earthquakes shook Turkey’s southeast, as well as parts of Syria, claiming at least 45,000 Turkish lives in what has become the biggest natural disaster in modern Turkish history. The country’s most pressing challenge is to provide relief for the more than 13 million citizens who live in areas directly affected by the tremors. In the meantime, however, in addition to exposing egregious zoning and building code violations, the powerful quakes have revealed new dimensions of anti-Syrian feeling in Turkey. In the days that followed, gruesome videos circulated on social media showing vigilantes battering individuals they accused of looting in the affected provinces. Syrian refugees have seen their noncitizen status exacerbated by local resentment, resulting in limited access to earthquake relief resources; they have likewise been especially vulnerable to the vigilantism. “Looting” and “Syrian” have become synonymous in some corners of social media, fueling public resentment centered on the refugee population. But hate directed at Syrians on the Turkish web is nothing new.

Turkey has seen an overall uptick in anti-refugee violence since 2021, often targeting Syrians. In a particularly violent episode in August 2021, residents of the Altindag district in Ankara vandalized and looted Syrian-run businesses and homes. Across 2022 and into 2023, even before the earthquakes, hate crimes against Syrians have continued to increase.

Turkey hosts at least 4 million refugees—3.7 million of them Syrian nationals or stateless people who have migrated from Syria. This is an almost 5 percent addition to Turkey’s existing population, which stood at about 74 million before their arrival, making it the largest influx to Turkey since the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, amid the Ottoman Empire’s collapse. Since the Syrian war began in 2011, the Turkish government has welcomed large numbers of Syrian refugees and given them “temporary protected status.” While the public in general welcomed them, since Turkey fell into recession in 2018, tolerance has worn thin.

This public unease has found expression in a media trend known as “street interviews,” which simultaneously spread intolerance and misinformation regarding Turkey’s Syrian refugee population. By way of context, the Turkish government has cracked down on conventional media over the past decade and a half, giving loyal media a monopoly on information and pushing Turkish citizens to seek alternative sources of news. Creative new initiatives have emerged as a result, some anchored in social media, and while these can fill gaps and contribute in meaningful ways, some, such as street interviews, are quasi-journalistic and can disseminate dangerous messages. If the Turkish government does not ease its hold over the media, other such trends will likely persist and continue shaping public opinion, hurting chiefly Turkey’s vulnerable Syrian population.

A Brief History of Syrians in Turkey

According to the Turkish Presidency of Migration Management, a government agency under the Interior Ministry, the first wave of Syrian refugees to Turkey dates to April 29, 2011, following growing clashes between protesters and the Syrian government. On that day, some four hundred Syrians rushed to the Cilvegozu border crossing in Turkey’s Hatay province, across from Aleppo, Syria’s largest city. By the end of 2012, the Syrian refugee count in Turkey had reached 100,000, and less than two years later, the figure exceeded one million.

While refugee is useful linguistic shorthand, from a legal point of view, it is a misnomer for Turkey’s Syrian population. Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, aka the UN Refugee Treaty—a multilateral accord that defines the term and outlines the rights of a refugee. When Turkey ratified the treaty in 1962, it imposed restrictions, defining refugees as only those individuals affected by events occurring in Europe before 1951. Ankara later dropped the temporal limitation, but it retains the geographical limitation. This means that most Syrians in Turkey—excepting those who have become Turkish citizens—occupy the ambiguous status of persons under “temporary protection.”

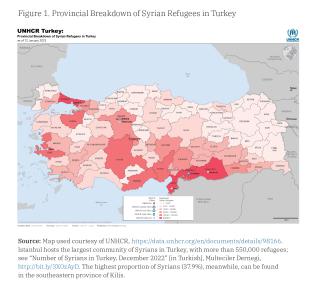

Temporary protection is, nevertheless, a legal term often invoked by nations in times of mass human flight during humanitarian crises, whereby the host state grants civilians permission to stay on its territory for a limited period without promise of permanent residency or citizenship. Under UN guidelines, refugees lose temporary protection when they obtain an alternative status in the host country or relocate to a third country. Most important, temporary protection ends once the crisis causing the displacement ends. Of the 3.7 million Syrians in Turkey, according to data from the UN Refugee Agency, 3.5 million are under temporary protection by the Turkish government, while around 200,000 hold Turkish citizenship. Open image

When violence gripped Syria in 2011, Turkey threw its support behind opponents of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, expecting that the regime would soon fall. As large groups of Syrians poured into the country, Ankara regarded their stay as temporary and pursued an open-door policy. Now, however, more than a decade has passed and Assad remains in power, his rule increasingly secure. Syrians in Turkey face a plethora of problems arising from their in-between legal status, inability to get work, and, increasingly, festering resentment from the Turkish public.

Public resentment against Syrian refugees has surged in Turkey’s domestic political debate, and an unwritten agreement between the main political factions not to exploit the refugee issue in election campaigns has broken down. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s administration has come under fire from key opposition leaders, who have blamed him for the refugee problem.

Anti-refugee sentiment also appears to be spreading in online forums. As conventional media such as newspapers lose stature, new media platforms like YouTube and internet-based journalism initiatives have grown and gained clout in the refugee discussion. The emergence of hateful alternative forums, paired with a closing space for free media in Turkey, has worsened the prevalence of unsavory and provocative messages against refugees. In response, Ankara would do well to promote freedom of expression and protect the country’s vulnerable refugee population by looking closely at the current state of alternative media and considering amending the government’s restrictive policies on press freedoms.

The Move to Social Media

Since around 2007, Turkish government watchdogs have confiscated various media outlets and handed them over to pro-Erdogan businesses in often single-bidder auctions through transactions funded by near interest-free loans from public banks. As a result, nearly 90 percent of the traditional media outlets—i.e., TV networks and newspapers—have come under pro-Erdogan or Erdogan-loyalist ownership. Turkey’s media watchdog, the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTUK), which is dominated by Erdogan-appointed members, routinely slaps the few remaining dissenting media outlets with hefty fines and broadcast bans.

Erdogan’s consolidation of media outlets has resulted in widespread distrust of Turkish media and, consequently, a migration to new media platforms—such as YouTube street interview channels, web-based journalism forums, and social media accounts—especially by young consumers. Content producers on these platforms tend not to observe the standards and practices of conventional journalism. Yet some fill a gap in the Turkish media landscape by producing credible and independent content and providing the Turkish public with an outlet for expression. Others, however, as already noted in the Syrian refugee context, can create and perpetuate hate speech and misinformation.

The citizens of Turkey, with its internet penetration rate of 82 percent and almost 70 million participants, are avid social media users. According to a Reuters Institute report, only social media has seen a rise in popularity as a news source in Turkey in recent years, while print and online news readership has dropped. Sixty-one percent of Turkish respondents to a survey report using social media for news, up from 35 percent in 2015, while 10 percent say that they rely on it exclusively.

The Turkish internet is by no means immune to government surveillance and control. In 2020, the Turkish parliament passed a law mandating that large social media platforms establish offices in Turkey to quickly respond to court orders to remove content, and all major platforms acquiesced. Nevertheless, social media giants like YouTube and Twitter can still provide a space for Turkish citizens to produce alternative news content.

Street Interviews

Government censorship has not only pushed Turkish citizens to seek out news on social media; it has also forced them to get creative, devising and boosting new genres, including those at the intersection of content creation and reporting—chief among them street interviews.

Produced and disseminated mainly through YouTube, then further marketed on platforms such as TikTok and Instagram to generate views, street interviews play a crucial role in Turkey’s new media landscape. In this burgeoning genre, the interviewer—rarely a trained reporter—approaches average Turkish citizens on the street with often controversial questions. Topics range from celebrity gossip to domestic politics, but the most hard-hitting and best-received street interviews address the common citizen’s frustrations with government. Some of the most successful interviews present compilations of citizens’ monologues on Turkey’s economic woes and frustrations with the country’s large refugee population.

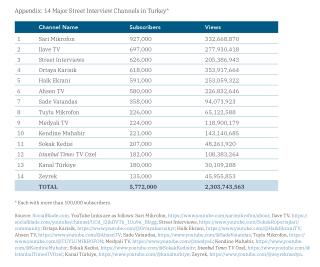

Turkey has at least fourteen major YouTube channels with more than 100,000 subscribers each (see appendix). Interestingly, all fourteen have repeatedly addressed the refugee question, amassing some 2 billion views to date as well as more than 5.5 million subscribers.

A likely contributor to the popularity of street interviews is the YouTube ad revenue scheme. According to Social Blade, a public YouTube analytics tool, Ilave TV, a major street interview channel, generates anywhere between $1,200 and $19,000 in ad revenues each month. Such monthly earnings vary based on view count, and public data suggests that some street interview channels, such as Halk Ekrani, earn up to $55,000 a month. When the figures are checked with an online revenue calculator, they generally track with the ranges provided on Social Blade. Whatever the vagaries of the Social Blade algorithm, even a conservative estimate equates to meaningful income in Turkey, where the lira’s value has nosedived: just three years ago, the exchange rate was about US$1:6 lira, but as of February 2023 it had widened threefold, to US$1:18 lira.

The political orientations of major street interview channels vary. While most appear critical of President Erdogan, channels such as Ahsen TV—run by political Islamist Turkish nationalists associated with the religious network known as “Ismailaga Cemaati”—are staunch Erdogan supporters. In videos produced by each major street interview channel, regardless of its political stance, intolerance of refugees stands out. With more than two billion views as of 2022, street interview videos—such as the viral clips featuring Syrian refugees hounded by angry Turks demanding that they “go back to Syria”—exhibit patterns that fuel anti-refugee sentiments and actions.

Ilave TV is a prime example of this new media wave. In August 2022, Ilave TV, with more than 600,000 subscribers, received on average 130,000 views daily and almost a million weekly. The channel has produced at least twelve anti-refugee street interview videos in the past three years, drawing more than five million views. For comparison, Turkey’s best-selling newspaper, Sabah, owned by pro-Erdogan businesses, sold 194,930 copies daily in 2021.

A video about a Syrian refugee’s plan to stay in Turkey—and vote for Erdogan—drew more than a million views. In it, a Syrian youth speaks to an Ilave TV reporter while passersby join the debate and denounce the Syrian. An outraged Turkish man rages about how Syrian refugees fled their country “like women” only to harass Turkish women and drive up rents in the country. Another Turkish man is seen pointing at the refugee and saying: “Whoever has it tough comes [to Turkey]. They come from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran…This is Turkey! Turkey’s over, over!”

A common thread in street interviews is the demand to expel Syrian refugees. In a street interview conducted by Halk Ekrani, thirty-three of forty interviewees, when asked if Syrian refugees should be deported, answered yes. While some voiced sympathy for the Syrians’ plight, the majority described Syrians as a “social excess” draining the country’s resources. This common view, which appears frequently in street interviews, rests on a few key themes.

Theme 1: The War Is Over

One of the most common questions street interviewers pose to their Syrian interviewees is about why Syrians remain in Turkey even though the war in Syria is “over.” They claim that refugees celebrate holidays in their native country and that if they can vacation in Syria, they can go back to live there.

Turkey does allow Syrian refugees wishing to visit family in Syria to cross the border around the time of religious holidays. This is likely intended to sustain Syrian refugees’ ties to their homeland and ultimately pave the way for their return, while also honoring religious sensitivities.

In reality, of course, the war in Syria is far from over. Foreign governments and militaries continue to operate in the country, and the Assad regime and allied fighters, such as the Russia-sponsored Wagner Group, continue to demonstrate brutality toward the civilian population, especially those who took part in the uprising against Damascus. While violence in Syria has declined, pockets of the country continue to face conflict.

Theme 2: Refugees Steal Turkish Jobs and Get Government Stipends

An accusation hurled frequently at refugees is that they snatch jobs from Turkish citizens. In an Ilave TV video, a passerby claims that for “every job that a Syrian gets, a Turkish youth loses theirs.” A study done in Istanbul confirms that many in Turkey share this sentiment: 64 percent of Istanbul residents surveyed claimed that Syrian refugees were an economic burden, while almost 71 percent said that Syrians reduce job opportunities for existing residents. Yet while the entry of millions of refugees into Turkey’s (official and unofficial) workforce has increased competition, that is hardly the whole story. Many refugees in Turkey work in unfavorable conditions, often in unpopular heavy industry jobs, for comparatively low pay. Workplace violence against refugees is also prevalent: Mustafa Colak, a Syrian national living in Istanbul, was fatally attacked by seven co-workers in August 2022.

The anti-refugee side in Turkey also claims that, in addition to “stealing jobs,” Syrian migrants receive monthly payments from the Turkish government. While some refugees are eligible for an EU-financed card from Kizilay (the Turkish Red Crescent) that grants them 230 Turkish lira (roughly $12) a month in humanitarian aid, arguments that they receive a monthly salary from the Turkish government are unfounded.

Street interviews often paint Syrians as the culprits in Turkey’s economic decline. Interviews that set out to probe questions not directly related to the Syrian question—such as surging inflation—consistently morph into heated discussions about Syrian refugees. A major street interview channel, Sade Vatandas, sought in July 2022 to cover the rising prices of goods in the southeastern province of Gaziantep, which hosts the country’s second-largest Syrian community, with 460,000-plus refugees, about 18 percent of its population. Within a few minutes, interviewees’ grievances about inflation devolved into a collective complaint that the Turkish government favors Syrian refugees over Turkish citizens. An elderly woman expressed regret about the government’s resource allocation, saying that the government “used to provide [Turks] with coal. Now they give it to Syrians.” A young woman, visibly agitated, pleaded with Ankara to allow Syrian refugees to cross the border into Europe, claiming that once they leave, their own husbands will find jobs, Turkish artisans will get more business, and rents will stop increasing. Her speech drew applause.

The misconception about refugees’ outsize responsibility for Turkish economic hardships has taken unexpected forms in street interviews. In a bizarre episode highlighting this distortion, a Turkish citizen blamed Syrians for his inability to afford bananas. The video by Kanal Dunya (Channel World), located on YouTube, went viral, sparking a countertrend in which people claiming to be Syrian refugees shared TikTok videos of themselves eating bananas. This footage was met with outrage from Turks on social media, leading the government to deport forty-five refugees for posting “provocative” social media content.

Theme 3: Refugees Get Education Without Having to Take Exams

Every June, Turkish high school seniors and graduates interested in pursuing higher education sit for a two-day national university entrance exam. The competition is cutthroat; more than three million people took the test in 2022. And a persistent myth in Turkey holds that refugees are allowed to bypass the national exam.

In fact, the university entrance journey can be significantly more arduous and expensive for Syrian refugees. All foreign nationals residing in Turkey, regardless of legal status, are subject to the same admissions procedures. Syrian refugees are considered international applicants and take “foreign student exams” administered by each institution to select candidates to fill the typically low international student quotas. As every university offers its own admissions test, foreign test-takers often have to cover the registration fees for multiple exams.

Theme 4: Refugees Constitute a Societal Threat

Testimonies featured in street interviews suggest that a portion of the Turkish public believes refugees pose a threat to security, the “Turkish way of life,” and women. Moreover, a study by the Economic, Social, and Political Research Foundation of Turkey found that a frequent complaint against Syrian refugees was that their presence prevented locals from using recreational urban spaces; 59.8 percent of those polled claimed that Syrians were a threat to the “modern way of life.” The study noted that some Turkish citizens saw Syrian refugees as a threat to secularism, associating them with social conservatism and Turkey’s distancing from the West.

Street interview subjects often observe that Syrian refugees are overwhelmingly male, frequently suggesting thereafter that they are cowards who fled the Syrian conflict, leaving women and children behind. Recent data on Turkey’s Syrian refugee population does not bear this out. According to the Refugees Association—a nonprofit based in Turkey—more than 70 percent of all Syrians in Turkey are women and children. Interviewees also voice concern about what they see as a failure to control the admission of refugees, alleging that some are criminals. In one unconfirmed anecdote from a street interview, the interviewee accuses a Syrian refugee deli owner of decapitating a Turkish soldier in Syria before he fled the country. Widespread mistrust of Syrian refugees can be observed in a Medyali TV street interview in which a Turkish man warns that Syrian refugees will “in ten years become spies and sell [Turks] out,” an allegation drawing cheers from the crowd.

The perceived threat to Turkish women comes up often. “Every day, you [Syrians] are out bothering women,” ranted a Turkish man to a Syrian refugee in an Ilave TV street interview. The man was likely referring to a series of incidents that received broad media attention, in which several videos showing women from compromising angles were alleged to have been circulated by Syrian, Afghan, and Pakistani refugee men. In the commotion that followed, Turkish citizens called on the government to relocate the country’s refugees to protect women.

Conclusion

In a street interview, one Gaziantep resident stated, “I used to be the number-one supporter of Erdogan. Now, I am the last to support him. These Syrians will destroy Tayyip [Erdogan].” Such sentiments are commonly expressed in street interviews by former Erdogan supporters.

Street interviews take place in all Turkish provinces, and the demographic groups commonly represented in these interviews—mostly working- and middle-class voters who, despite making up most of the Turkish electorate, are often underrepresented in conventional media—set the interviews apart in meaningful ways. While street interviews do not adhere to methodological standards of journalism or polling, they still provide invaluable insight into the grievances of broader Turkish society while also fanning social tensions.

The Turkish public’s impatience with its Syrian guests is not lost on Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, as evidenced by increased deportation rhetoric by officials and, in some cases, actual deportations. Turkish interior minister Suleyman Soylu has repeatedly issued statements in favor of sending refugees back en masse. The Turkish Presidency of Migration Management revealed in November 2022 that Turkey had deported some 100,000 “irregular migrants” in the first eleven months of the year, bringing total deportations since 2016 to 427,000. Ankara has also completed housing projects in Turkish-held northwest Syria to house repatriated Syrians, without regard to their preconflict place of residence.

The refugee question will be among the most debated topics ahead of Turkey’s 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections, with possible consequences for the country’s Syrian population. This is due in part to emerging and unregulated media trends like street interviews.

Ankara should recognize that as it shrinks the space for reliable media, it also pushes Turkish media consumers—who remember a more democratic country and oppose government-controlled stories and headlines—to seek alternative venues where hateful language, bigotry, and racism toward Syrians run rampant. The government’s hyper-control of the media sparks misinformation, encouraging the spread outside conventional journalism of harmful anti-refugee rhetoric. Ankara would thus be wise to expand the Turkish media space in the run-up to the 2023 elections, allowing for credible journalists to operate freely instead of letting fringe commentators dominate the narrative on social media, now the information source for large portions of the Turkish public. The government could also help counter the misinformation-laden narrative by supporting initiatives to integrate Syrian refugees, who have stayed longer than initially envisioned.

Ankara’s impulse to welcome Syrian refugees was driven by a laudable sense of compassion, even if accompanied by strategic considerations. Now, Turkey’s leaders have an opportunity to rethink the costs of a narrowing media space and how restoring media freedoms could counter hateful narratives, ensure national stability, and safeguard the future of the Syrian refugee population. Open image

Sude Akgundogdu is a research assistant in The Washington Institute’s Turkish Research Program.

By Sude Akgundogdu in Washington Institute on March 20, 2023.