Guardian, July 24, 2021, Elif Ince

‘I felt I existed in this world’: TikTok gives a voice to Turkey’s labourers:

Workers in Turkish factories, construction sites and fields have become the unlikely stars of TikTok, revealing harsh and dangerous conditions in posts with millions of views. Turkey, ranked among the ’10 worst countries in the world for workers’, is one of TikTok’s largest user bases, with approximately 19.2 million users. Its algorithm can allow a labourer with a handful of followers to reach millions if their posts land on the ‘discover’ page. But despite the grim reality evident in these videos, creativity and humour shine through the cracks.

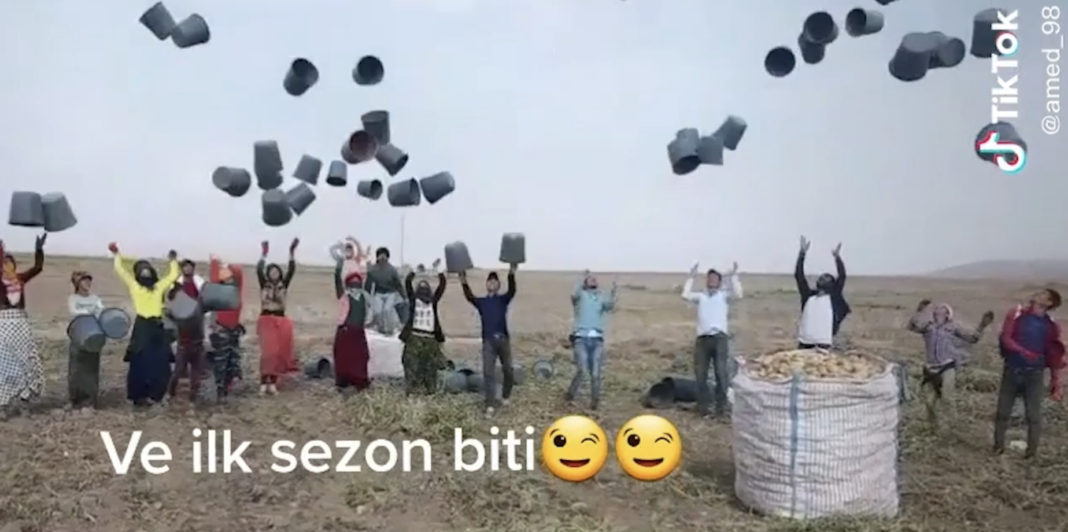

Agricultural workers throw their buckets into the air at the end of harvest like at a graduation ceremony. A construction site turnsinto a concert hall, with workers wearing strands of hemp as wigs and singing into bits of plastic piping instead of microphones. A market stall becomes a runway as fruit vendors strut their stuff: a bunch of bananas as headgear, leeks dangling from their necks.

With posts from factories, fields and construction sites, workers in Turkey are going viral on TikTok. The app’s staples such as challenges, dancing and comedy abound, but amid the joy it is hard not to miss the criticism of dire working conditions.

Turkey was ranked among the 10 worst countries in the world for workers for the sixth year in a row by the International Trade Union Confederation’s 2021 Global Rights Index.

Conditions for workers got steadily worse after the 2016 coup attempt against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and subsequent two-year-long state of emergency, while the pandemic gave Ankara yet another excuse to ban rallies and dismiss thousands of union members.

Ahmet İstek, who is collecting lentils for £8 to £12 a day and living in a tent without access to hot water or a stove, said children as young as 13 were working alongside him – a common sight in many of the TikTok videos posted by agricultural workers.

“We have no union, no insurance, nobody to defend our rights,” İstek said. “So we use TikTok to criticise our work conditions and show how difficult it is to earn a living.”

At least 2,427 workers were killed on the job in Turkey last year, excluding deaths from occupational diseases, according to Health and Safety Labour Watch (İSİG), a campaign group that keeps track of work accidents – more than anywhere else in Europe.

Construction is one of the deadliest industries. In one video, a worker descends from the sixth floor of a building’s scaffolding in a mere 15 seconds, climbing down swiftly without any safety equipment while a Kurdish song plays in the background. Another is working on a newly finished high-rise, nonchalantly disassembling the scaffolding he is standing on, wearing a hoodie instead of a helmet and a harness that is not attached to a rope.

Aslı Odman, a researcher with İSİG and faculty member at Mimar Sinan University’s department of urban and regional planning, said TikTok was exposing Turkey’s middle-class, for the first time, to the “hidden realities of manual labour”.

“These labourers are the bulk of the new working-class,” Odman said. “They are young, they all have smartphones, and they want to get likes.”

Turkey is one of TikTok’s largest user bases, with approximately 19.2 million users. Its algorithm can allow a labourer with a handful of followers to reach millions if their posts land on the “discover” page.

When posts by workers started getting popular on the app last year, Karşı Sanat, an art gallery in Istanbul, took notice and made a compilation for an online exhibition launched in January.

Ozan Çağlar, one of the curators, said the team was fascinated by the language of the videos: “A crossover between fiction and documentary.”

The documentary aspect makes hidden production processes visible, he added: “Workers on TikTok are revealing how those jeans advertised on Instagram were made.”

Ahmet Tezcan regularly posts on TikTok, showing how to break up enormous rocks used in construction – some of his videos have more than 30m views. He puts spikes in the rock and hits them with a hammer, one by one, waiting until there is a cracking sound, and runs out of the way as the rock splits in two. He is not wearing any safety gear: no goggles, no hard hat. In one post, he calls out to Erdoğan: “Mr President, you say to stay at home because of the coronavirus, but we are (or we will be) hungry. If we don’t work, who will take care of us then?”

For many in Turkey, TikTok has become a way to organise, since it became impossible to do so in the workplace or on the street. “Of course a TikTok challenge is no May Day rally, but this could definitely lead to something bigger,” Çağlar said.

Despite the grim reality for Turkish labourers evident in the TikTok videos, creativity and humour shine through the cracks.

“We see workers breaking stereotypes, showing themselves at play, having fun and being witty,” Çağlar said. “They are well aware of the exploitation but prove they are much more than a bunch of hands on the assembly line.”

Construction worker Barış Kaya was ecstatic when his video, in which he makes paving stones, overlaid with a sad song, went viral to get 1.7m views. “You work so hard yet it feels like nobody knows what you do,” said Kaya, 25, who lives in southern Turkey’s Şanlıurfa province.

“I felt like other people saw me, like I was alive and actually existed in this world.”