Hakan Kara is professor of monetary policy and financial markets practice at Bilkent University in Ankara. He was previously chief economist at the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. Published on Nikkei Asia of the 3rd of July 2023

Is Turkey’s experiment with unconventional monetary policy over?

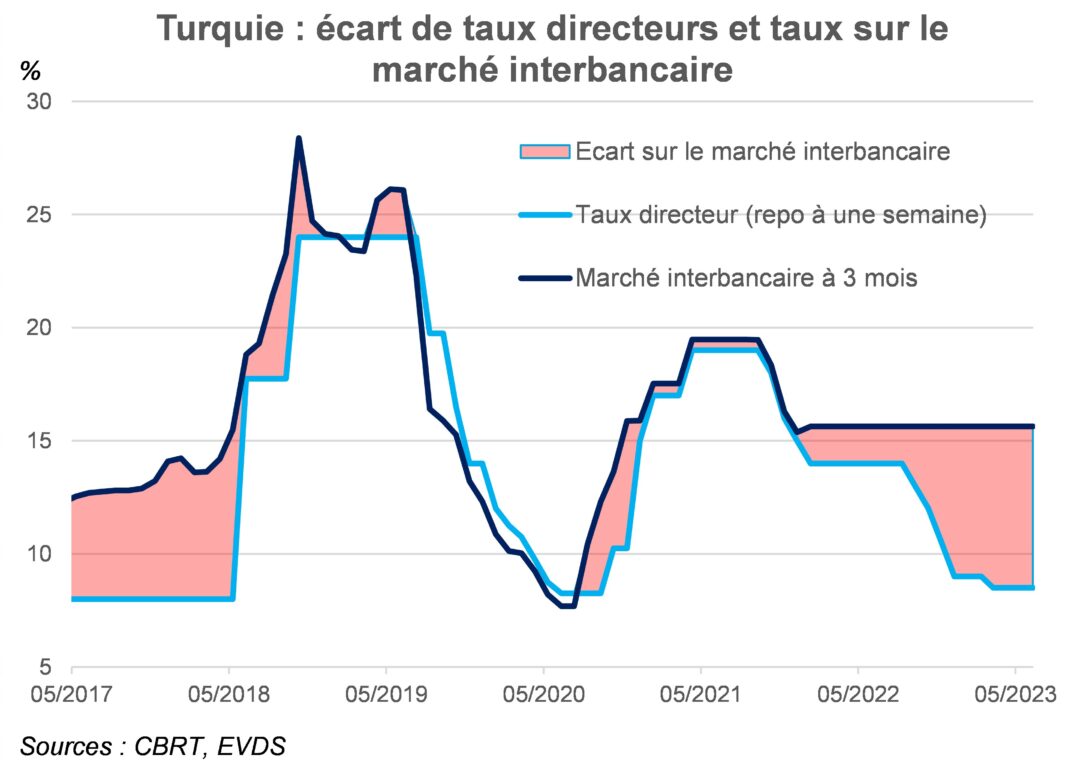

Some signs suggest it may be. Since winning reelection on May 28, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has replaced the country’s central bank governor and the minister of treasury and finance with relatively market-friendly figures. At its first rate meeting under Hafize Gaye Erkan on June 22, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey raised its policy rate from 8.5% to 15% and gave some indications of an intention to normalize policy.

But it is not yet clear whether Turkey’s policy experiment, which began in 2021, is finished.

It all started when Turkey’s central bank began moving to cut interest rates at a time everybody else in the world was doing the opposite. Shortly after the initiation of this controversial policy, inflation went out of control.

By mid-2022, the official consumer price index was up more than 80% from a year earlier. Real interest rates consequentially dropped to record low negative levels compared with those of Turkey’s peer economies.

Unsurprisingly, the immediate impact of this monetary policy experiment was a marked deterioration in inflation expectations. This was accompanied by a sharp depreciation of the lira, with the Turkish currency losing 70% of its value against the dollar after September 2021.

The authorities introduced a number of measures to stabilize the lira, aiming to offset the damaging effects of the exceedingly low policy rate. The currency regime shifted to heavily managed exchange rates, in part through opaque sales of foreign reserves via public banks as well as extensive exchange and credit controls. The government also introduced a lira deposit protection program at the expense of inflating contingent liabilities on the public budget and inflating banks’ regulatory burden.

To be fair, through their financial repression policies, the authorities were able to rein in currency depreciation and keep the benchmark interest rate at a low level through the period leading up to the presidential election.

Stable exchange rates and buoyant domestic demand fueled by extremely loose monetary conditions helped the ruling coalition to retain power. But this came at the expense of depleting the reserves of the central bank, the accumulation of immense imbalances in the form of runaway inflation, a high external deficit and a complex set of financial regulations that distorted the efficient allocation of financial resources.

The moves taken since May’s election do signal a U-turn, in apparent reaction to balance of payment stress, but getting back to fully conventional policy will not be simple.

The journey will be conditional in part on the central bank’s willingness and ability to normalize policy interest rates, a prerequisite for unwinding the complicated set of regulations imposed on banks over the last two years.

If policy rates remain politically constrained, a full normalization of the regulatory framework will not be feasible in the near term because, in order to control the exchange rate and domestic financial conditions with a low policy rate, the regulators will have to keep most existing restrictions for an extended period.

Although the central bank nearly doubled its benchmark rate, this will not be enough to reverse the deterioration in the public’s inflation expectations. According to surveys, the public expects inflation, now close to 40%, to still be above 30% in a year’s time.

The authorities have revealed a preference to stay gentle with interest rate decisions, which in practice will initially mean keeping the policy rate way below expectations. But gradualism can be effective only if institutions have high credibility. At this point, the central bank’s initial moves may be seen as a signal that the authorities are not willing to pay the costs of disinflation until after local elections next year.

Inflation remains elevated and still needs to be brought down decisively to avoid longer-term inflation expectations becoming entrenched. By delaying necessary adjustments now, the authorities may be sowing the seeds of a deeper downturn later.

To be sure, the gradualist approach might yield higher growth in the short term. Yet this may come at the expense of a more protracted slowdown in economic activity down the road.

Staying gentle today will mean more currency weakness and hence more inflation in the future, which will necessitate even higher interest rates then. Due to a rapid pass-through effect with the exchange rate, the lira’s 30% weakening since the election in May will add about 15 percentage points to inflation through the end of the year and possibly push the official inflation rate back above 50% by year-end.

Assuming the authorities are serious about fighting inflation, this means the terminal level of the interest rate needed to control inflation is now even higher than the level required a month ago. Keeping interest rates low today will necessitate tighter policy in the future. Gradualism may not be as growth-friendly as hoped by the authorities.

While the government may be able to attract fresh direct investment flows from Gulf states to support the exchange rate and economic growth, such forms of funding cannot be sustained for a long period without addressing the country’s macro-financial vulnerabilities.

There is no free lunch in economics. Turkey has accumulated substantial macro imbalances over the past few years and eventually, the bill must be paid.

To minimize that cost, what is needed now is an urgent stabilization program that prioritizes disinflation and fiscal consolidation on the back of a fast improvement in the credibility of institutions. This will require more front-loaded, though not excessive, monetary tightening backed by a proper level of fiscal adjustment and an internally consistent macroeconomic program that would restore confidence in the lira.

The root cause of current macroeconomic imbalances, including inflation and the country’s external deficit, has been the lack of an anchor to assure the public and companies that prices are stabilizing. A credible macroeconomic program that anchors inflation expectations would mitigate the magnitude of any prospective recession.

This would also facilitate a smoother exit from the country’s current inefficient financial regulations. The cost of normalization need not be that high under a well-formulated program implemented by credible actors.

It remains to be seen whether recent personnel appointments will bring such a fundamental change in policy approach. Will the newcomers be given the latitude they need to navigate the economy toward a sustainable path?

Although initial steps have not been convincing enough, it may be too early to make a concrete call. Perhaps we should lean toward giving the newcomers the benefit of the doubt at this stage, stay cautious and hope for positive surprises.