There’s a lot of Trump-Erdoğan comparisons out there. Most are from the liberal perspective, and talk about the similarities between the two men. There’s pieces in the Washington Post in 2018, the FT in 2017 and 2024, the Independent in 2020, the Chicago Sun-Times in 2023, as well as many academic articles and talks.

Kültürkampft, November 4, 2024

There is a weird mind meld between the bases of the two men. One Turkish poll indicates that more people in Turkey favor Trump than favor Harris, and there’s international outfits confirming the finding. That sounds right to me. There might be a bit of tactical calculation behind this, especially concerning US support for the PYD in Syria, but I don’t think that’s a huge factor. There isn’t really enough information about that in the Turkish media sphere. I think it’s more about gut feeling. Harris is the status quo candidate, and thus Turkish voters usually like things that go against the status quo. They also like Trump’s uninhibited style. (I first made that argument in FP in November 2016.)

What I want to do here is to look at presidents Erdoğan and Trump in a bit more detail. Sure, both are right-wing reactionaries, but what else is similar about them? And crucially, what’s different about them? Does the comparison help us think about the men and the movements they lead? Does it help us think about these types of movements, and their pathways to power?

Let’s go through the comparison. Some of this is about the proclivities of the men themselves, but a lot of it is about the movements they lead and the political energy they exude.Similarities

Similarities

There’s a lot to choose from on this list, and I tried to go from the most general to the more specific items.

Revivalism

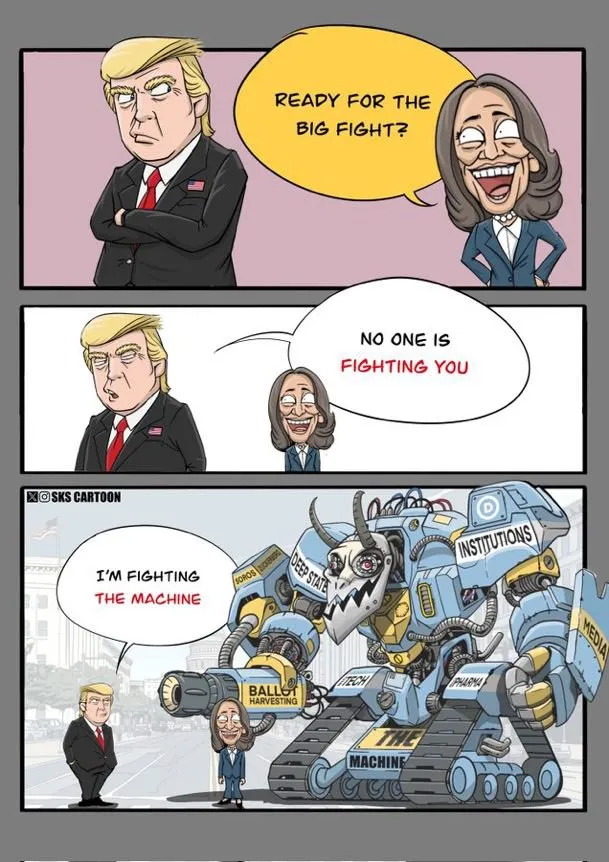

I won’t spend a lot of time on this, but it’s worth noting at the outset that both leaders are reacting to a status quo. Sometimes they refer to it as the “Deep State,” a term that may have traveled from Turkey to the United States. Other terms are the bureaucratic oligarchy, the administrative state, or “müesses nizam” meaning the “established order” or “üst akıl” meaning “the high mind.”

Both promise to “take back” the power of the state, enlist it in the service of the people, and initiate a period of national revival. Hence Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again.” In the Turkish context, the key term is “diriliş,” meaning “revival,” and there are other slogans attached to that, like “the century of Turkey.” Both movements are versions of Palingenetic nationalism

We could get into other aspects of their politics, like their depiction of their rivals, the “enemies within” mentality, the use of conspiracy theories, the emphasis on the wholesome nation, but I think that comes with this territory. I’m going to skip all that and focus on the more structural aspects.

Theory of executive power

Both men believe that state power should be centralized in the hands of the executive. Neither has respect for the judiciary and legislative branches as separate branches. The movements both men represent also have broader theories to institutionalize this proclivity.

In Turkey, the theorizing and institutionalization is fairly shallow. The AK Party was born in the 1990s, when coalition governments wrecked the country’s economic base. Their priority has always been to avoid coalitions at all costs. I remember a founder of the AK Party telling me that they’d prefer the CHP to be in power rather than having to deal with a power-sharing arrangement. In the 2010s, as Erdoğan’s star was rising, this morphed into a theory of executive superiority. They ended up calling it a “Turkish-style presidency” and implemented it in a plebiscite after the 2016 coup attempt. I’ve written about that elsewhere for anyone interested in the details.

In the United States, the constitutional structure is more rigid. Trump, after all, couldn’t enact his authoritarian instincts during his first term. This being the US though, the intellectual firepower behind the authoritarian drive is also much greater. Trump supporters like the “Unitary Executive Theory,” which would imbue the presidency with far greater powers, allowing them to enact radical changes to the U.S. government. This is essentially the same thing as the “Turkish-style presidency.” You seize power and adjust things so that you’ll restart the Republic with new values and a new vision.

So both movements are based on the authoritarian intuition that the leader of the country should be able to control pretty much all of the state, and by extension, all of civil society and the private sector. Erdoğan is obviously much farther along in the realization of this goal than Trump is, but if Trump should win this election, he might start to move much faster in this direction.

Institutional battle

Both leaders have identified the bureaucratic apparatus (aided by the establishment media) as their real enemy, with status-quo politicians merely serving as the handmaidens of those elites.

I’ve written about Erdoğan’s theory of the “institutional oligarchy” elsewhere. As mentioned above, MAGA has (knowingly or not) adopted the Turkish term “deep state” to describe their opponents (Ryan Gingeras has written an excellent piece on that). I’d point out that the term has a slightly different meaning in the two countries, mostly because they’re on different points in their far-right trajectory. In Turkey, the Islamists ran against the “deep state” in the 1990s and 2000s, then became the deep state in the 2010s (a related term is “müesses nizam” meaning “estnalihsed order”). So here, the “deep state” was always right-wing, it just switched from a Kemalist-Turkish character into an Islamist-Turkist character.

In MAGA’s collective imagination, the “deep state” is a liberal/managerial/leftist/Marxist/statist machine. Unlike in the Islamist example, there’s varying ideas in MAGA on what to do with it. There’s the libertarian group (Vivek Ramaswamy, etc.) that wants simply to abolish it, and there’s a more statist group that wants to make it “national,” implying a change of character. The latter is closer to the Islamist example.

Building big

Erdoğan and Trump both like to imprint the world with massive buildings. They are both great builders of pyramids.

With Erdoğan, this manifests itself in huge mosques, the third Bosphorus bridge, the gigantic Istanbul airport, a Manhattan Skyscraper across the street from the UN, and of course, the massive palace (across the street from our offices at TEPAV).

Trump has made a career out of building big shiny buildings and putting his name on them. What’s more interesting here is Elon Musk, who’s practically on the Trump ticket. Musk builds megaprojects of an entirely different scale, including space exploration and renewable energy. He’s also to be made the head of a new “government efficiency” force that would be tasked to cut red tape and make such projects easier to undertake. I can see how this would be appealing. It has become far too difficult to build things in rich countries. I’m just not sure how the MAGA movement would make it easier.

I think there is a sense in both movements that the bureaucratic mechanisms are needlessly in the way, and that they would simply bulldoze their way through them. Both movements also subscribe to the idea that governance isn’t really about making people’s lives incrementally better, it’s about satisfying people with the grandeur these large projects bestow on the nation.

Religion

As you’ll see below, this is a factor in both columns. The commonality they have is that they use religious symbols, and appeal heavily to the religious side of the secular-religious cleavage. This is significant because there’s a good argument to be made that both men are immoral in their individual personal dealings (in terms of corruption, and in Trump’s case, sexual exploits). Organized religion is thereby decoupled from individual morality, and attaches itself to an older form of blood and soil nationalism.

Natural resources:

Both men are fascinated by the extraction of natural resources, seeing them as a shortcut to national wealth. Trump is campaigning on “drill baby drill,” by which he means that he’s open to fracking, especially in the electorally important Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Erdoğan meanwhile, is searching for hydrocarbons in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. “Those who find are always those who search” he likes to say, and it plays really well with the public. Many Islamists have a hard time believing that Turkey does not have significant hydrocarbon deposits of its own, claiming that Western powers know where it is, but keep Turkey from developing it.

As with much else on this list, there are massive policy differences here, but the politics is pretty similar.

Other commonalities

There are a lot of other things I could list here. The two men involving their families at the highest levels of governance, their thinking on military power, their preference for dealing with strong leaders over institutions, their thoughts on family, their quasi-mercantilist approach to the economy… I think those are a little less interesting/important for now.

Differences

Competence

There’s a huge difference in how focused these men are, and how skilled they are at the job of politics and government.

Erdoğan has been in politics all of his life and takes it extremely seriously. He is attentive in meetings, takes notes, asks questions, and isn’t easily distracted. His political ground game remains very strong. One of his mottos is that “he who runs with love does not tire” and he himself works around the clock, getting deep into the weeds on every issue. To be clear, Erdoğan has basically zero knowledge of the fundamentals (economics, history, philosophy, foreign languages), but he is a natural strategist and manager.

Trump may be fairly good at winning elections, but he’s very bad at pretty much everything else pertaining to the job. He barely has any structure or impulse control. He gets impatient in meetings, and picks people by the way they look, or how prestigious their degrees are. People report that he barely has a functioning cabinet, and that he often assigns tasks to whoever is closest to him. Trump also played around 260 rounds of golf during his four years as president. I don’t think Erdoğan has taken that much time off in his entire life.

Staff relations

Granted, this is part of the above, but I think it merits a separate mention.

According to the Brookings Institute, Trump had a 85% turnover in his A team during his presidency. Many highly qualified people joined his cabinet, then either resigned or were summarily fired. Some of them wrote books about their former boss, and almost none support him in his second presidential bid. That includes Mike Pence, his VP.

This is why Trump is always weary of being handled by his own people. He’s very easy to manipulate based on very reactive arguments (“I suggest you do X because Obama would have hated it”) so people compete based on those terms.

Erdoğan, on the other hand, has extremely low turnover. Getting into his inner circle is very difficult to do, but once you get there, you can stay there for a very long time. The A team right now — Altun, Fidan, Kalın, Şimşek, and a few others — have been with him for decades, even if there were some bumps along the road.

Some people who serve at this level simply retire, as was the case with Binali Yıldırım. Most of the people who do leave Erdoğan’s side eventually re-join in some way later on. Even if they don’t, however, and even — as in the case of Davutoğlu and Babacan — if they campaign against him, they don’t talk out of school. The interactions in Erdoğan’s A team are air-tight, and the public will probably never know what goes on between these figures.

One might argue that Trump is still in the early phase of his movement, where there is a lot of turnover, while Erdoğan has advanced to a later stage, where there isn’t. The Republican Party is still going through its metamorphosis, but the AK Party has long ago completed its.

Religious observance

Easy. One man is deeply religious, the other obviously isn’t.

Does that matter though? In American policy discourse, analysts often characterize Muslim leaders especially as being either “ideological” or “pragmatic,” which gives them an easy counterintuitive insight. “The mullahs may appear to be religious crackpots who want to blow up the world, but I’m here to tell you that they’re actually pragmatic!” That kind of thing.

I think every religious commitment is ultimately performative and utilitarian, but it does matter how deep one is caught up in the performance. Trump holds up a Bible every once in a while and says nice things about Christians (“I love Christians. I’m not Christian”), but he can’t name a single book of the Bible, much less quote it. Erdoğan, meanwhile, has a full religious education, and is actually pretty strong on the details. He can recite long prayers by heart, has excellent pronunciation, can converse on theological points, and is visibly observant.

I don’t think that Erdogan really draws on religious concepts when he makes important decisions, but in Turkey and its region, religion does restrict the parameters of what’s politically possible. Religious orthodoxy has died, but a secular language hasn’t really settled yet. This is why, when we speak of “Islamists” in the Turkish context, we’re not talking about a theological commitment, but more a branch of romantic nationalism.

This is also significant when it comes to elite formation. The elite around Erdoğan is going to be pretty uniform Sunni Muslim (Hanefi-Maturidi, to be precise). Meanwhile, Trump can be loosely “religious,” and the US being as diverse as it is, he can draw various Christian, Jewish, and Muslim denominations into his orbit, and it’ll work. So while that deep religious performance does award Erdoğan a certain charisma, it is still restrictive. Secular people are turned off by him. Trump’s loose commitment to help religious people in general probably allows him to build broader coalitions.

Immigration

This is getting specific, but it’s a significant difference between the politics of the two men. I think this mostly reflects a developmental difference between Turkey and the US, but it’s still important.

Trump of course, strongly opposes immigration. A major part of his appeal lies in his willingness to call immigrants criminals who “poison the blood” of America. He also keeps promising to build walls and stage mass deportations.

Erdoğan, on the other hand, is enthusiastically for immigration. If it wasn’t so deeply unpopular, he’d open the borders and invite half of Syria into the country. It works for his preferred economic model, and it certainly works for his political notion of the country.

At bottom, however, both men are implying that their countries should be civilizationally wholistic. Trump wants to keep people out because they’re not wealthy Westerners, but poor people from the Global South. Erdoğan likes the immigrants because they pull the country into the civilizational direction he wants the country to travel in.

Those are the main points of comparison I can think of. These things are imprecise though, and I’m sure you guys have your own opinions, so let me know what you think. Especially if Trump wins tomorrow. If he loses, we can probably retire this list.

Kültürkampf is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support their work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.