« Last week’s earthquake killed tens of thousands of people, made many more individuals homeless, and exposed the shoddy underpinnings of the AKP economic miracle. » Tessa Fox analyzes in Foreign Policy on February 13, 2023.

Initial shock from the largest earthquake to hit Turkey in the last 100 years has shifted to anger. And just as the fragile buildings in southern Turkey crumbled, so too might the government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

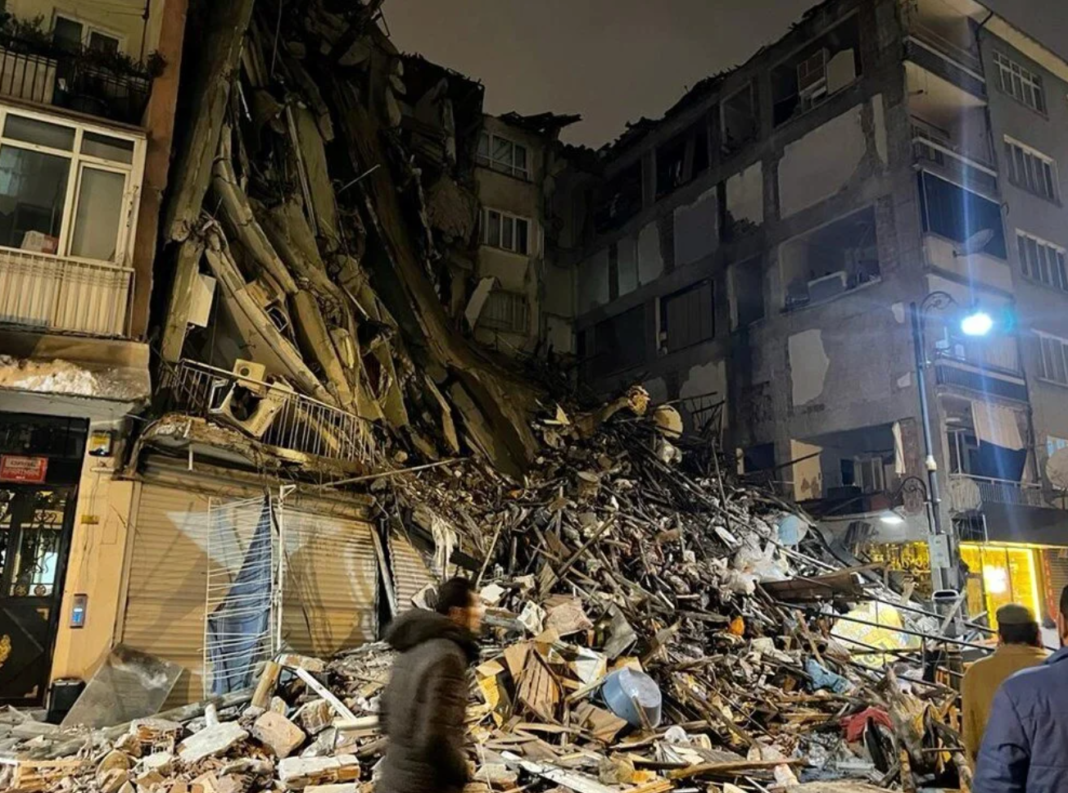

Turkish elections come in May. What came earlier was a hellstorm of devastation. At least 35,000 people have died in the catastrophe—a natural as well as building disaster. Although infrastructure and development have been the main selling points of Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) to his constituencies for the last 20 years, shoddy construction might actually see him crumble.

Ankara is going after the builders. In what some people say is a smokescreen, Turkish Vice President Fuat Oktay announced on Saturday that 131 suspects have been identified as linked to the collapse of buildings across 10 provinces. So far, 113 arrest warrants have been issued and 12 people are in custody, including the developer of a 12-story residential complex that collapsed in Antakya and who was detained at Istanbul Airport before boarding a flight to Montenegro on Friday. Of an assessed 170,000 buildings across the affected region, 24,921 structures have collapsed or are heavily damaged, according to Turkish Environment Minister Murat Kurum.

Before the 7.8 magnitude quake, which also killed thousands of people in northern Syria, the focus of Turkey’s election was on the usual suspects: a terrible economy and thriving migrants. Now, though, the critical lens is trained on tardy relief efforts, a missing or misused so-called earthquake tax, and a now deadly construction boom rooted in nepotism.

When Erdogan spoke to those affected in Kahramanmaras, near the epicenter of the earthquake in southern Turkey on Wednesday, he put the destruction and losses down to “fate’s plan,” dismissing any criticism of slow relief efforts. Erdogan also condemned those criticizing the efforts and stated, “It’s not possible to be ready for a disaster like this.”

But scientists have long warned that a major earthquake was overdue in Turkey. Legislation has been passed to try to prepare for the devastation that occurred in the 1999 earthquake of nearly the same magnitude—one that, incidentally, ousted a government—but it has either been overlooked or taken advantage of.

The Erdogan government passed a zoning amnesty law in 2018 that allowed any property built without a license or in violation of construction permits or zoning laws to be granted a building certificate and avoid demolition. Turkey was certainly not Tokyo when it came to earthquakes.

“Crony capitalism was baked into many of Turkey’s structures, with massive societal cost,” said Lisel Hintz of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. The humanitarian crisis in Turkey is “partially man-made.”

The fallen buildings left at least 1 million people homeless. Meantime, fallen bricks and timbers are easy to spot; rescue teams were harder to spy. The slow deployment of rescue teams to destroyed homes bred anger across the provinces. People sleep on the streets—gathering wood from collapsed buildings for fires to keep warm—due to the lack of temporary shelters erected by disaster response teams. The shift to a presidential system has bred sclerosis. It took two days to see military assistance on the streets, for example.

“The scale of death and destruction is beyond the capacity of Turkey’s resources, and the reality is that every country has a finite number of resources,” said Yusuf Erim, a political analyst in Ankara at TRT World.

Turkey’s been here before. Then-Turkish Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit’s government had a poor response after the 7.6 magnitude Izmit earthquake in 1999, which killed upward of 17,000 people and ushered in Erdogan as president. That’s what’s now looming over the AKP leader as he faces the May 14 election.

The slow response in 1999 fueled anger among survivors, aggravated by the clearly unsafe construction people had been living in. Erdogan had promised to rebuild the country, which he did—but with the greatest benefit going to businessmen close to the AKP. The rapid expansion over the last two decades—which saw new bridges, malls, mosques, skyscrapers, and (of course) the government-backed Housing Development Administration (TOKI) pop up everywhere—seems to now have come at a cost.

The arrest warrants seem too little, too late for tens of thousands of victims, especially when building codes—which say they meet seismic engineering standards in Turkey—evidently haven’t been enforced.

There is always severe political polarization in Turkey, particularly at election time and most predominantly between supporters of AKP and the main opposition party, the social-democratic Republican People’s Party. But this time around, the same kind of cracks that tore down southern Turkey menace Erdogan.

According to Erim, the earthquake has made all previous election polls irrelevant. “Every party has a three-month clean slate, and their performance during this period will determine the result of May elections,” he said.

Of the 10 provinces hit by the earthquake, six are traditionally AKP strongholds. In the 2018 elections in Adiyaman, one of the cities badly affected by the earthquake, the AKP won 70 percent of the votes. There has been criticism that Hatay, near Turkey’s border with Syria, has received less aid or support due to its votes normally going to the opposition.

Considering the devastation the earthquake has wrought, there is a possibility the elections won’t even take place in May, due to an inability to organize voting. “There are not even addresses anymore,” said Sinem Adar of the Centre for Applied Turkey Studies in Berlin.

Postponing the election would actually favor the government, giving it more time to make it up to supporters again. But according to the constitution, the vote can’t be pushed back for more than a month. Only when a state of emergency is triggered by a war can it be postponed for longer; therefore, the state of emergency Turkey declared due to the earthquake doesn’t qualify.

Once the election does go ahead, the “construction as manifestation of the government’s capacity to deliver,” as Adar put it, is a narrative that can no longer be used. It will also be harder for Erdogan to tout a “strong” Turkey independent of the West, given the outpouring of international aid needed to deal with the aftermath of the quake.

“The earthquake by itself, similar to the economic crisis, will not be by itself an end to the Erdogan regime, but it would certainly weaken the legitimacy of the existing ruling alliance,” Adar said.

Read also : How Corruption and Misrule Made Turkey’s Earthquake Deadlier

Foreign Policy February 13, 2023 by Tessa Fox.