Turkey’s new spy bill, compared to Russia’s, may limit journalists and civil society, sparking fears of further curbing freedom of expression.

The Jerusalem Post, May 21, 2024, by Kristina Jovanovski

A reported new spy bill in Turkey, which is being compared to Russia’s foreign agent law, is sparking concerns that journalists and civil society will face greater limits on freedom of expression.

The Ankara-based Anka News Agency wrote that the law would imprison people who work on behalf of foreign countries or organizations that oppose the interests of the Turkish state.

The pro-government newspaper Yeni Şafak stated that the government is developing a law about so-called influence agents who are accused of using propaganda against Turkey on social media.

Journalists could be labelled as spies

The state news website TRT Haber also reported that the Turkish government is working on a bill to define a new type of espionage connected to foreign intelligence organizations.

Özgür Ünlühisarcıklı, the German Marshall Fund’s Ankara office director, told The Media Line that he is concerned the law would be applied arbitrarily and that the priority would be to discourage dissent.

“They tend to frighten the innocent, law-abiding citizens while they do not deter potential criminals,” he said.

“Foreign-funded NGOs, foreign-funded media groups, media platforms, and even individual journalists receiving foreign funds would immediately come to mind. So, basically, anyone could be accused,” Ünlühisarcıklı said.

In the 2024 press freedom index published by Reporters Without Borders, Turkey placed 158th out of 180 countries. The report cited that while seven journalists are currently behind bars, many more have been imprisoned in the past.

News consumers in the country have often turned to Turkish-language websites run by foreign government-funded news organizations for independent reporting amid a clampdown on the press.

In 2022, Turkey’s media regulator said that it had blocked the websites of US-funded Voice of America and German-funded Deutsche Welle because they had not obtained the licenses required by the government.

Ünlühisarcıklı said that Ankara may have been inspired to create the new bill by laws in both Russia and Georgia.

Georgia has seen mass protests for weeks because the government is attempting to pass a bill requiring NGOs and news organizations to register as agents pursuing foreign interests if they get more than 20% of their funding from foreign sources.

White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter that the US was alarmed at democratic backsliding in Georgia.

“Georgian Parliamentarians face a critical choice – whether to support the Georgian people’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations or pass a Kremlin-style foreign agents’ law that runs counter to democratic values,” Sullivan wrote.

Meanwhile, Russia first introduced a law on “foreign agents” in 2012 that has been used against media organizations and individuals who express dissent from President Vladimir Putin.

Media restrictions in Turkey accelerated after the 2013 anti-government Gezi Park protests and intensified even more after the failed 2016 coup attempt.

Reporters Without Borders stated that 90% of national media in Turkey is under government control, and in the run-up to last year’s national elections, dozens of Kurdish journalists were arrested.

Earlier this month, police tear-gassed and shot at journalists with rubber bullets while they covered a banned protest, according to global non-profit organization the Committee to Project Journalists.

Last week, the organization said that journalists in Turkey who had worked for a pro-Kurdish paper were sentenced to more than three years in prison for “aiding a terrorist organization without being a member.”

A 2023 report by the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford found that the opposition-leaning Fox TV was the most trusted Turkish news organization. According to the report, 58% of respondents found this media outlet trustworthy.

Gürkhan Özturan, a media freedom monitoring officer at the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, told The Media Line that the law would target a new level of civil society and news outlets that use international donors.

He said the law would make international news organizations that had workers in Turkey especially vulnerable.

“It’s definitely going to have a chilling effect, and this will deteriorate the already fragile and heavily chaotic media freedom and free expression field in Turkey,” Özturan stated.

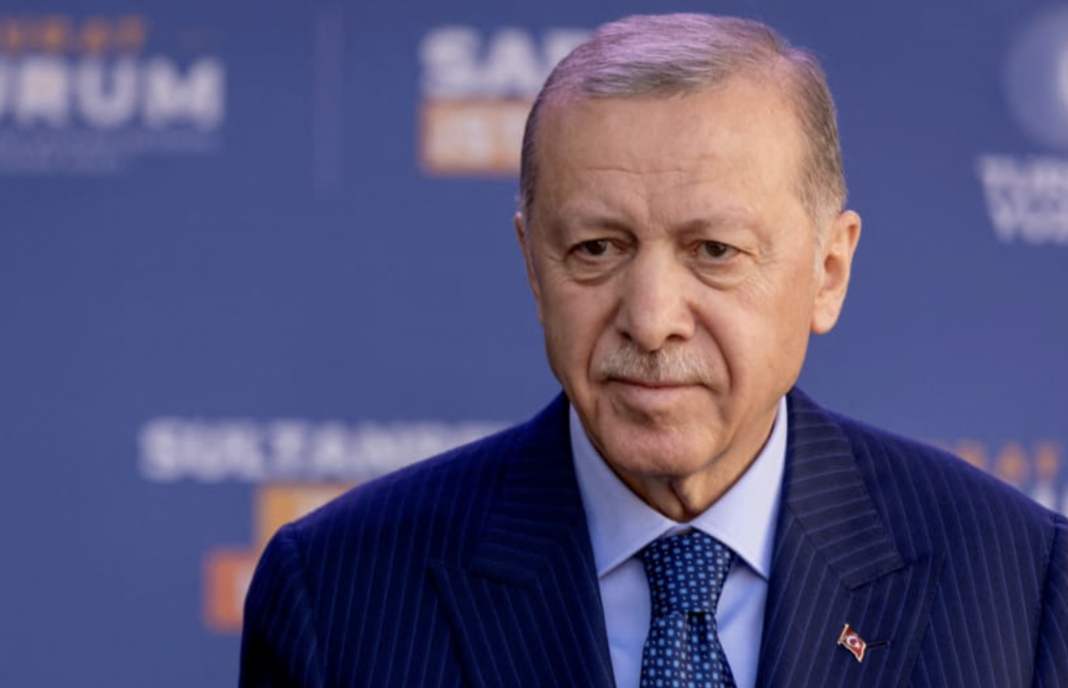

He believes the government wanted to create such a law after nationwide local elections in April led to major losses for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party and his coalition.

“They have noticed that the reactions against the party, against the governing alliance, has come to a point of unimaginable levels,” Özturan said.