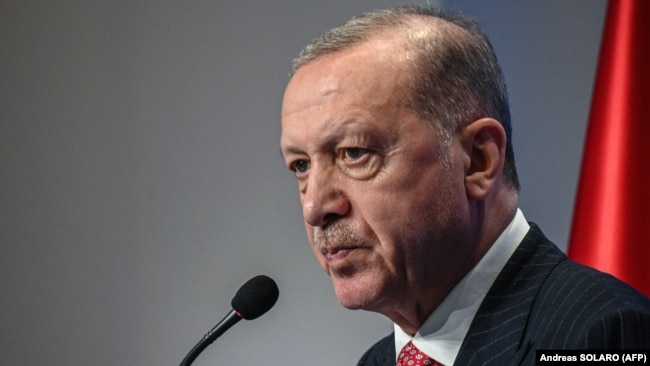

« Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan might be aiming to tighten his grip on the domestic front, taking advantage of Ankara’s rising profile amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine » says Pinar Tremblay in Al-Monitor.

A Turkish court sentencing of prominent Turkish philanthropist and businessman Osman Kavala and seven other defendants on April 25 in the trial over the 2013 nationwide Gezi Park protests against the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) government has worried activists that further harsh sentencing may become the norm.

Kavala was sentenced to life in prison without parole while the others were sentenced to 18 years in jail each. The ruling came as a surprise to many, as observers, legal experts and civic groups deem the charges politically motivated and question the independence of the judiciary.

Most pundits have a difficult time even referring to the process as a “trial,” while a few prominent AKP figures publicly criticized the “unlawful decisions.”

The crucial question is: At a time when Turkey is in desperate need of financial stability and Ankara has just begun to improve its tarnished image among the international community, why did Turkish authorities under pressure from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan come down so harsh nine years after the protests?

After talking to government officials and pundits following the case, we can provide three explanations.

First, Turkey’s executive presidency has deprived the country of almost all of the checks and balances mechanism, handing full authority to Erdogan. The verdict has widely been considered a message to both domestic and international society that dissent against Erdogan will be punished in the harshest way regardless of whether these punishments are lawful. Turkey’s civil society and human right activists have taken several hits from the government in the last decade.

Erdogan blamed the Gezi protests — the first massive public uproar against his rule — on Turkey’s foreign enemies and their « pawns » at home. The coup attempt coming three years later aiming to overthrow Erdogan’s government helped him to further strengthen this rhetoric. Turkey accuses US-based Sunni cleric Fethullah Gulen of masterminding the coup attempt during which 250 people were killed.

The verdict also cemented Erdogan’s loutish image among international public opinion. “The life sentence meted out to Osman Kavala for legitimate, peaceful opposition to the government reveals to the world the brittleness and paranoia that characterize Erdogan’s thuggish dictatorship,” president of the Middle East Forum Daniel Pipes told Al-Monitor. “I look forward to the day when Turkey again enjoys democracy and justice.”

The second explanation lies with Turkey’s strengthened geopolitical position amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Jonathan Schanzer, senior vice president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington, DC, told Al-Monitor, “My sense is that Erdogan is patching up ties with the West abroad for the good of Turkey’s economy and defense, but that domestic enemies are still useful for his power narrative. His means of governing has been consistently bolstered over the years by defining enemies for his base to hate or fear. It continues today.”

The third explanation is Erdogan’s need to consolidate his support base ahead of the June 2023 elections amid staggering inflation and soaring prices in Turkey. As full economic recovery seems like a far prospect in a year, Erdogan might be relying on populist sentiments to secure public support by portraying the Gezi protests as a ploy by Western capitals to overthrow his government.

AKP lawmaker Ibrahim Aydemir, speaking right after the trial, told press that the “[US] dollar went up from 1.70 to 2.40 liras during Gezi. Isn’t this treason?” He added that the protestors cost the nation $200 billion.

Henri Barkey, professor of international relations at Lehigh University, told Al-Monitor, “In a large measure, this [decision] is driven by Erdogan. He seems to have a problem with Kavala. It is almost personal. When you have been in power as long as he has and have ruled with absolute power, you have a sense of entitlement and cannot tolerate dissent.” Both Kavala and Barkey, a Turkey scholar based in the United States, were indicted for their alleged involvement in 2016 coup attempt. A Turkish court exonerated Kavala from those charges in 2020, only for him to be detained on the same day for other charges.

“But it is more than dissent; he accuses Kavala of being Turkey’s Soros. Kavala is more than just an ordinary opponent. Erdogan imagines him as being extraordinarily powerful. Like Putin and Navalny for whom he went to extraordinary lengths to kill and capture,” Barkey added.

The verdict, which has drawn harshly worded criticism from all Western capitals, earned praise from Erdogan who argued that the decision was made by Turkey’s independent judiciary.

Seren Selvi Korkmaz, co-founder of the Istanbul-based think tank IstanPol Institute, told Al-Monitor that under such a tough economic environment, the government has fewer options. “It can either do a reform or increase pressure on all sorts of dissent. Gezi protests could be a force of polarization for Turkish public opinion with a sizable portion of population considering it a terrorist act, a threat to national security. This could be a valuable resource to rally around Erdogan for AKP’s base.”

Barkey said, “Erdogan got really frightened of Gezi. It was two years into the Arab Spring, and he thought he may be next. This is also why in his comments he said a message was sent to others not to try something alike.”

Al-Monitor, May 2, 2022, Pinar Tremblay, Photo/Andreas Solaro/AFP