« Damascus’ low-key reaction to Turkey’s recent strikes on Syrian Kurdish targets suggests it might acquiesce to Turkish military moves that would contribute to ending the US military presence in the north » reports Fehim Tastekin in Al-Monitor.

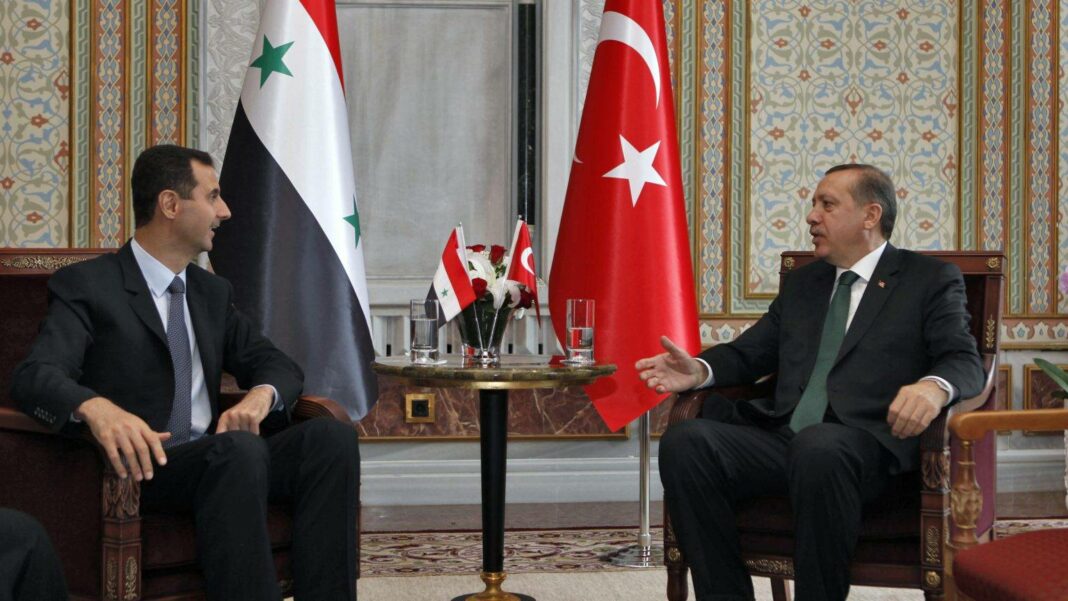

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan appears bent on launching a new ground operation in northern Syria following airstrikes that targeted Kurdish forces but caused losses in the Syrian army as well, while still extending an olive branch to Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad. Damascus, for its part, has kept its reactions remarkably low-key, refraining even from saying how many Syrian soldiers were killed, while it urges the withdrawal of existing Turkish troops as a key condition for normalization with Ankara. Only one calculus could explain this situation in which both sides contradict themselves: destroying all prospects of the Kurds gaining a constitutional status down the road after their establishment of de facto autonomy in the north.

According to Russia’s special Syria envoy Alexander Lavrentiev, contacts between the Turkish and Syrian intelligence chiefs have continued on a “fairly regular basis” — a statement that justifies questions about likely bargaining going on behind the scenes. Could Assad be acquiescing to Turkey’s strikes on Kurdish-held areas, even if grudgingly?

Erdogan’s plan, as he has frequently repeated, is to create a safe zone with a depth of 30 kilometers (19 miles) along the entire length of Turkey’s southern borders with Syria and Iraq. Speaking after the launch of Operation Claw-Sword, which has hit targets in both countries since Nov. 20, Erdogan said the security belt would be established “step by step, starting from festering points such as Tel Rifaat, Manbij and Ayn al-Arab” — all Kurdish-held towns in northern Syria.

Such an attitude could come off as undermining Ankara’s proposal for a new chapter with Damascus, but given Erdogan’s modus operandi, it is in no way inexplainable. It has to do with Erdogan’s pre-election strategies as well as Turkey’s relations with Russia. Since his Aug. 5 meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Erdogan’s reactions on any Syria-related issue, including security and refugees, have been in line with his reconciliation offer to Assad. On Nov. 21, he voiced hope that “things could get back on track with Syria, just as they did with Egypt,” asserting that “there is no place for hard feelings in politics.”

Peace with Damascus is among the opposition’s pledges ahead of the elections, due in June at the latest, so Erdogan does not want to lose this trump card to his opponents. He has said a new page could be turned with Syria after the polls, but recent developments signal he might meet with Assad earlier. Yet Assad appears to get on Erdogan’s nerves by not backing down from his conditions for dialogue: the withdrawal of Turkish forces from Syria and an end of Turkey’s support to armed rebels. Thus, Erdogan might be reckoning that a fresh military operation could help him impose his own fence-mending terms on Assad.

The first noteworthy Syrian reaction came eight days after the strikes began in a parliamentary statement accusing Turkey of “brutal massacres” and support for “terrorist groups” in Syria. Yet not even this statement mentioned the killing of Syrian soldiers in the strikes.

Damascus’ attitude could be attributed to several reasons. First, it might be hoping for the ripening of conditions where the United States can no longer protect the Kurds against Turkey. Damascus could hardly regain control of Kurdish-held areas to the east of the Euphrates as long as US forces are present there. Thus, pressure from NATO member Turkey that would push the Kurds toward Damascus could suit the Assad government’s book as well.

Remarkably, head of the Syrian parliament’s Foreign Affairs Commission Pierre Boutros Marjane described Turkey’s airstrikes as “a message to separatist Kurdish militia” in remarks to a Turkish news site, adding that “Syrian civilians and soldiers” were among the victims. He said Turkey’s concerns over the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) were understandable but stressed that not all Syrian Kurds “can be accused of treason, barring the separatist group armed by the United States.” He was referring to the People’s Protection Units — the backbone of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) — and its political arm, the Democratic Union Party, which have led the autonomy drive in the north. Ankara equates those groups with the PKK, which it designates as a terrorist group over its four-decade armed campaign in southeast Turkey.

According to Marjane, diplomatic dialogue between Ankara and Damascus could be restored on the basis of the 1998 Adana Accord on bilateral security cooperation and if Turkey “demonstrates readiness to withdraw from Syrian territory.”

Another reason for Damascus’ muted response is that it would have failed to follow up with action had it reacted with strong language. Also, it could rely less on Russian and Iranian protection now that the war in Ukraine has raised the value of Moscow’s ties with Ankara and Tehran is grappling with domestic unrest.

Syrian journalist Sarkis Kassargian told Al-Monitor, “Syria cannot hold out [against Turkey] without Russian or Iranian support. That’s the reason for its mild language. If it were to accuse Turkey, people would have asked ‘Why are you not responding?’ or questioned the [prospect of] normalization.”

In 2020, for instance, Turkish forces faced Russian bombardment as they attempted to stop the Syrian army’s advance along the crucial M5 motorway.

According to Kassargian, “The equilibrium has now changed” in Syria. “Russia is no longer restraining Turkey. Also, it is calling for reconciliation. Damascus has put forward conditions in line with its game plan. Turkey is reluctant to budge and says ‘Either you agree to normalization or I will pound you.’”

In the Astana process, Russia has heeded Turkish requests to express opposition to “separatist agendas” in the final communiques of the meetings. In talks after the latest escalation, the commander of the Russian forces in Syria reportedly pressed the SDF to consider withdrawing from border areas in favor of “the deployment of the Syrian army along the border strip at a depth of 30 kilometers” to fend off a Turkish ground operation. Such messages to the Kurds show that the Turkish threat is of instrumental value to Russia.

Kassargian dismissed the possibility of a tacit agreement to push the Kurds away from the United States. For him, a Turkish ground operation in areas to the east of the Euphrates is unlikely. “As for the west of the Euphrates … what the Russians say is what matters. They either give [Turkey] the green light or refuse to do so,” he said. The Turkish threat could be instrumental in pushing the Kurds closer to Damascus only if it concerns areas where the US greenlight is required, he opined, adding, “As long as the US support to the Kurds continues, a partial operation would not push them toward Damascus.”

Though popular anger with the SDF has grown over its ongoing partnership with the United States and control of oil-rich areas, Damascus is unwilling to fight the Kurds for Turkey’s sake. Also, it is clearly reluctant to give Erdogan an election gift. Syrian officials often feel the need to note that the Kurds have not taken up arms against the state and have fought terrorists, even receiving arms assistance from Damascus. In other words, they believe that Syrian anger with the Kurds should not play into Erdogan’s hands.

Al-Monitor, November 29, 2022, Fehim Tastekin, Photo/Osman Orsal/AFP