« The Turkish president’s response shows how out of touch he is with the scale of the event. » Sinan Ciddi’s analysis in The Dispatch on February 21, 2023.

Two weeks have passed since the deadliest series of earthquakes in Turkish history destroyed 10 provinces in the country’s southeast. The death toll could surpass 100,000, and many survivors have lost not just their homes but their livelihoods. Yet President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has appeared more concerned about the disaster’s political fallout than aiding its victims.

His politics-first approach ahead of national elections in May has backfired. Now voters are demanding accountability for haphazard rescue and relief operations—as well as the corruption that gave rise to substandard buildings that collapsed in seconds.

Erdoğan’s reelection chances were already uncertain amid a floundering economy. Before the earthquakes hit, he had launched an economic plan to win over skeptical voters: He increased minimum wage and pensions and loosened monetary supply, flooding money markets with low interest loans for businesses and individuals. On the foreign policy side, he demonized Turkey’s Western partners and accused them, among other things, of being behind a violent 2016 coup attempt. Such tactics gained traction, and Erdoğan’s poll numbers ticked up in the last quarter of 2022. Erdoğan was also buoyed by a visibly incompetent political opposition consisting of six parties under the umbrella of the “Nation Alliance,” which has no clear message and has not been able to nominate a candidate to stand against Erdoğan. The impact of the quakes have likely nullified the utility of this playbook. Now, estimates suggest that post-quake reconstruction could cost $84 billion and the loss of economic activity could shave 2 percentage points off Turkey’s projected gross domestic product growth in 2023. This hampers the government’s ability to curb inflation.

His struggle to hold onto power is now more difficult. The quakes prompted widespread public anger with Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP): Why were the rescue and relief efforts so slow and so badly coordinated? Why did the government hesitate to deploy the military? Why were building and occupancy permits given out by local officials for substandard dwellings that collapsed easily? What happened to the funds collected under the so-called “earthquake tax” imposed after the 1999 earthquake to prepare for future disasters?

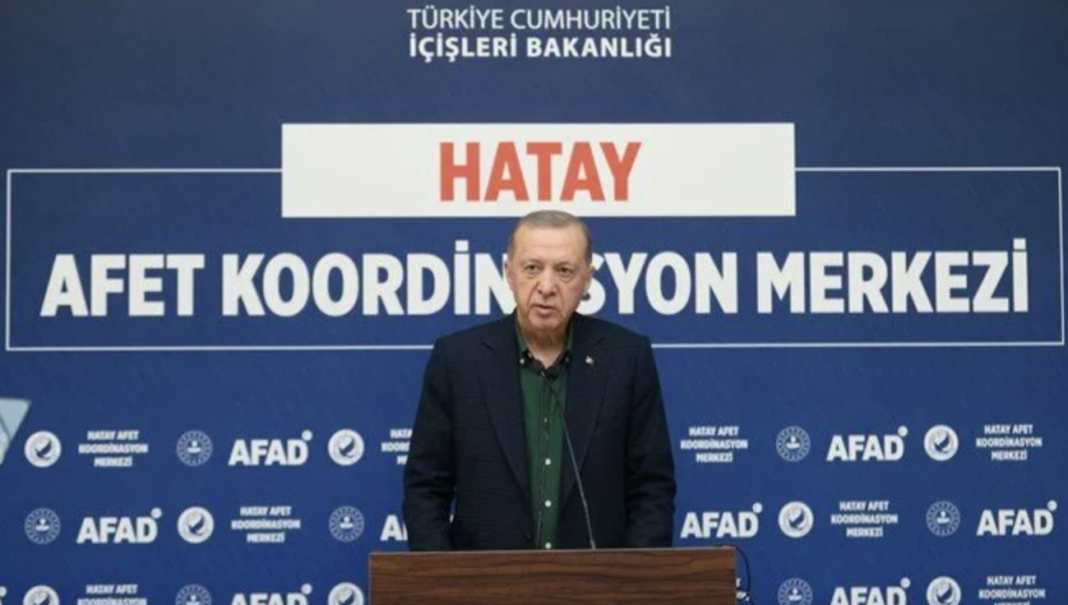

Erdoğan has no good answers to these questions, which likely explains his absence from public view in the first 48 hours after the quakes struck. In his first public remarks, he threatened legal action against those who criticized the government. Authorities also arrested more than 100 building contractors allegedly responsible for shoddy construction, but this is unlikely to satisfy public demands for accountability. Why not arrest the officials—in many cases affiliated with the AKP—who issued the building permits? Instead, the day after the disaster, Erdoğan blocked access to Twitter, where criticism of the government was proliferating. Rescue workers quickly condemned that decision, because victims trapped under the rubble were using social media to communicate their locations to rescue teams.

As citizens watch their government respond to the country’s biggest natural disaster on record, they are convinced of one thing: Their president is uniquely focused on limiting his and the AKP’s political exposure and responsibility for the disaster. Demolition crews have been dispatched to destroy public records office buildings that housed building permits, along with the names and records of contractors and the public officials who approved such projects. In other words, it is the beginning of a coverup. Various aid workers also told press outlets they were pushed out of the way just as victims were being brought out of collapsed buildings, then replaced by government-affiliated aid workers who wanted to take the credit for the rescue in front of television cameras.

Erdoğan and AKP officials are beginning to understand that their pre-earthquake strategy to woo voters is now useless, while their earthquake response has caused widespread public anger. That’s why the AKP is considering postponing the election (even though it’s not legally possible). Article 78 of the Turkish constitution does not permit delaying elections unless the country is in a state of war. To attempt this would be tantamount to a civil coup.

On the other hand, delaying the election may not save Erdoğan. If the economy contracts after the quake, economic conditions may be worse, leading voters to call for Erdoğan’s ouster more vociferously. Moreover, Erdoğan’s anti-Western rhetoric may not be as persuasive now that Turkey has seen rescue teams from dozens of nations working around the clock to save the lives of earthquake victims. Teams have arrived from the United States, Israel, Greece, Spain, and Sweden. Even Cyprus, whose relationship with Turkey has been hostile for decades, offered to send a team. Against this backdrop, Erdoğan likely knows he has to rethink his weaponization of foreign policy.

That adjustment will be hard for a man who thrives on polarization. What kind of campaign can he run that does not demonize the West? On the other hand, how can he look people in the eye after being in power for more than 20 years and say that he and his party are not responsible for the loose building regulations that engulf Turkey and that he and the AKP can rebuild Turkish cities in a safe and timely manner? This is a perfect political storm for Erdoğan, one he was not prepared for. Perhaps his best hope is that the opposition will be equally uncertain of how to campaign in this brand-new environment.

The Dispatch, February 21, 2023, by Sinan Ciddi.