Feminists have updated the strike, whose basic meaning is work stoppage, by not performing any form of paid, unpaid, physical, emotional labor that the capitalist patriarchy expects from them. And the “care strike” entered our agenda with feminist strikes.

Çatlak Zemin English, April 30, 2024, by Coşku Çelik

In the third decade of the 21st century, the pandemic, climate crisis, food crisis, wars and the most recent catastrophic earthquake, which are the main crises facing global capitalism, differ in terms of their content and causes, but it is possible to state that these crises are the expression of the structural contradictions of 21st century global capitalism and bring even deeper crises with them. Indeed, the current global economic and social crises, especially the pandemic, have exposed a structural contradiction inherent in capitalism more clearly than ever before: Capitalism, which is based on the production of life, is a system that massively produces death. In Susan Ferguson’s words, this is what we have seen with the pandemic: When capitalism has to choose between the health of the economy (capital accumulation) and the health of workers, it prefers the health of capital and this is an indication that capitalism sides with death over life. When necessary for capitalist accumulation, the working class can die at work, from a virus, starvation, war, police brutality, air pollution caused by thermal power plants, ecological destruction, lack of water, or the collapse of a house that has been robbed of its iron in an earthquake while sleeping to prepare for the next working day.

In this article[1], I try to hold a social reproduction-centered discussion on the gendered character of the crises and disasters we are experiencing and how this provides us with a ground for rethinking class struggle. In doing so, I argue that class struggle and feminist struggle cannot be constructed separately from each other and from other fields such as the ecological struggle and the struggle against racism. Disaster capitalism has shown us again and again in the 2020s that each of these are integral elements of anti-capitalist struggle and the importance of combining these struggles in combating our political catastrophe in Turkey. Indeed, the distinguishing feature of our political catastrophe is not that capitalism is underdeveloped or arbitrary with nepotism relations, but that a mature, highly aggressive and highly patriarchal capitalism has come together with an authoritarian political regime. When I say our political catastrophe, I am not just talking about “natural” events. I mean all the relations of power that usurp the most basic rights of workers, withdraw from the Istanbul Convention overnight, criminalize LGBTI+s, condemn people to homelessness, hunger and deep poverty.

The concept of social reproduction (SRP), which has been discussed in various forms in feminist political economy literature since the early 1970s, basically refers to the processes by which people -especially laborers- produce and sustain life and reproduce labor power on a daily and intergenerational basis, including food, clothing, housing, health, education and security. In feminist political economy literature, the concept focuses on the processes of daily and intergenerational production and reproduction of labor power by drawing attention to the interaction, balance of power and contradictions of various institutions (state, market, family/household, civil society) (Bezanson and Luxton, 2006: 3). For example, the birth and care of a child is a process of reproduction as the production of the next generation of labor power. When a worker goes to work every day rested, fed and ready for a new day at work, this is a process of daily reproduction. Elderly care is a process of social reproduction of the previous generation of labor power. Therefore, the concept is used in the sense of the production and reproduction of labor power, which is the only commodity for capitalism, and in doing so, socialist feminism takes a methodological position that is both nourished by Marxism and critical of Marxism.

The SRP approach makes an important correction to Marxism regarding the definition of the working class. Classical Marxism’s definition of the working class includes those who live by selling their labor power to capital for a wage in order to make a living because they are cut off from the ownership of the means of production. But should those who do not own the means of production, or who, even if they do, cannot make a living from them, but who do not and/or cannot sell their labor directly to capital for wages, not be included in the definition of the working class? The answer of the SRP approach to this question is no. Rather than treating wage work as the only form of labor and wage workers as the only component of the working class and class struggle, it proceeds from a heterogeneous definition of working classes. Thus, it gives the opportunity to transcend dichotomies such as wage/non-wage labor, self-employed/paid employee, urban/rural, landowner/non-landowner. Therefore, it proposes to construct the fundamental contradiction of capitalism not between wage labor and capital, but between all forms of labor, life and capital (see Von Werlhof, 2007). Indeed, the ideal of capitalism is not to turn all forms of labor into wage labor, but to put all forms of labor, life and nature at the service of capital accumulation at the lowest cost.

The concept of disaster capitalism was introduced by Naomi Klein (2007) to explain the ways in which capitalism turns disasters into opportunities creating opportunities for capital accumulation. However, disaster capitalism not only turns disasters into opportunities, but as Foti Benlisoy explains, it produces and is based on disasters. Therefore, disaster is a necessary element for capitalism. Thus, disasters are not the result of breaks from the ordinary course of capitalism, but rather the product of pure capitalism. And capitalism’s reflex to solve the destruction it has created is possible only by reproducing itself in a new and more destructive and looting way. In short, through disaster capitalism. The SRP approach allows us to clearly see the historical and structural relationship between disasters. For example, the pandemic was defined by socialist feminists as a crisis of caring and social reproduction (see Mezzadri 2020; Bhattacharya 2020). Indeed, the pandemic has made it clearer than ever how indispensable the production of life is to the functioning of capitalism. At various scales, it exposed the vitality of care services and the destructiveness of inequalities in access to these services. With the declaration of the pandemic, educational and childcare institutions were closed (and in cases where they were reopened, the possibility of re-closure was on the agenda at any time); access to health and care services for the elderly and the chronically ill was restricted; it became difficult to benefit from paid domestic cleaning and care services; and household work burdens such as cooking, cleaning, laundry and shopping increased as the household population was locked in the house together. Each of these was met by women’s unpaid labor within the household. In any cycle of capitalism, such a crisis of caring and SRP would have been devastating. However, the fact that it happened under neoliberalism made the pandemic even more devastating because of two features of the neoliberal SRP regime. First, the intense capitalist attack on all means of production and livelihood outside capital relations. The confiscation of the means of production and livelihood of subsistence food producers in the countryside, widespread land grabs, and growth models based on natural resource exploitation have created a serious wave of dispossession and workerization, especially in the Global South.Secondly, during this period, the state’s withdrawal from the role of care and SRP to a great extent, and the marketization and/or informalization of these services. In other words, it was a period of commodification of health, education, housing, electricity used in housing, and food consumed. This wave of workerization also meant the feminization of paid work. Therefore, looking at these two features, it can be said that: neoliberalism’s fundamental SRP contradiction is, on the one hand, the increasing participation of women in the paid workforce due to the rising wave of dispossession and workerization, and, on the other hand, the increasing transfer of caring to the household and women’s unpaid labor due to the state’s withdrawal from SRP roles.

When caring and the production of life, the daily and intergenerational production and reproduction of the working class is so vital for capitalist accumulation, the capitalist state can withdraw from its role of the SRP by relying on patriarchy and unpaid female labor in the household. For example, in Turkey, which has tried to survive two major disasters in the last three years without the state, there is a question that has been rightly asked frequently since the February 6 earthquake: Where is the state? Although this question is asked during acute disasters such as pandemics and earthquakes, the state is absent even in non-catastrophic conditions, condemning children to go to school hungry when there is a deep food crisis, or denying housing as a social right and making people homeless in the face of rising housing and food prices. Therefore, the state, which breathes down people’s necks with its authoritarianism, is “absent” in caring and SRP services, and the institutions responsible for caring and SRP have been completely emptied. A critical question to ask here is why we feel the absence of the state less outside of disasters. Again, the answer lies in the household and women’s invisible domestic labor. This is a labor that is systematically invisibilized not only by the state but also by mainstream and critical economics as it is outside the wage relationship. However, under “normal” conditions, caring and SRP do not disappear spontaneously; women replace the responsibilities that the state withdraws from with their unpaid labor within the household. This is precisely why one of our most fundamental responsibilities in the fight against disaster capitalism today is to fight to make this labor visible.

In such a situation, what should the class struggle target? Today in Turkey, we have to construct a class struggle centered on caring and SRP against disaster capitalism and our political catastrophe. For this, feminist strikes, which are not limited to times of disaster and have forced us to rethink one of the most important working-class struggle practices, the strike, offer an important framework.

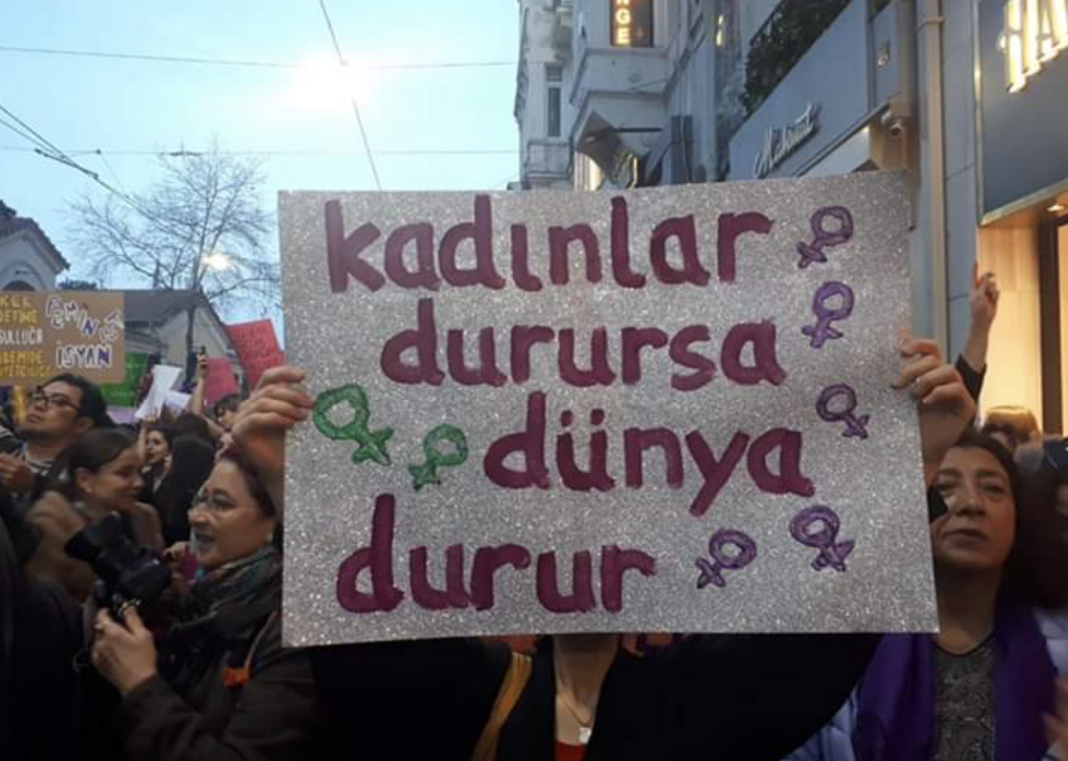

The socialist feminist movement has been claiming to reinvent the strike for some time. For example, the first thesis of the manifesto Feminism for the 99 Percent was the need to reinvent the strike. Feminist strikes have also entered the agenda of feminist politics, mainly through the International Women’s Strike organized in 2017, but it is also worth mentioning the Black Protest in Poland in 2016. On the day of the Black Protest, women in Poland gave up unpaid care work as well as paid work. They did not do housework, they did not look after children, they did not have sex with their partners, they did not smile… Similarly, on March 8, 2018, a nationwide feminist strike was organized in Spain. In the strike, which aimed at both paid and unpaid labor, both equal pay for equal work was demanded and male violence and patriarchy were targeted. The sectors in which the feminist strike was most actively organized were the social reproduction and caring sectors where women work intensively; health workers and education workers were among the pioneers of the feminist strike. The main slogan of the strike, “if we stop, the world stops”, was critical for understanding the political meaning of the strike. Indeed, when women stop, not only capitalist production stops, not only capital’s profits decrease. Life stops. Children cannot be taken care of, the sick cannot be taken care of, households go hungry… Therefore, feminists updated the strike, whose basic meaning is work stoppage, by not performing any form of labor -paid, unpaid, physical, emotional- that capitalist patriarchy expects from them. And a form of struggle that can also be defined as a “care strike” entered our agenda with feminist strikes. Paula Varela explains the role of feminist strikes in the inseparability of feminist struggle and class struggle as follows in the case of the feminist strike organized against abortion bans in Argentina in 2018:

“This is the goal of the women’s movement: to build bridges with working women (who are already part of the workers’ organizations) and to collectively discuss how to make these organizations see the feminist agenda as their own. Not as an external agenda but as an agenda of its own, because the problems of women are the problems of the working class as a whole. Women are half of the working class, we are the majority of the teachers and nurses, we have the majority of the precarious jobs, and we perform the overwhelming majority of reproductive work at home. This is why, a basic right such as the freedom to decide about one’s own body, to decide on motherhood, is a right for which the entire working class has to fight for. Similarly, that’s why the precariousness of work, the lack of funds for health and education (which took the life of two teachers last week), the extension of the working day (which makes the double burden of housework and paid work unbearable), all these attacks on the working class have to be demands of the feminist movement.”

In other words, feminist strikes constituted a form of struggle that identified with the labor movement but also updated it. By suspending not only paid work but also the unpaid labor of social reproduction, they exposed the indispensable role of caring and social reproduction in capitalist society.

So what can feminist strikes tell us about feminist struggle and class struggle in today’s Turkey? For example, not giving up on the Istanbul Convention should be at the center of all labor organizations, socialist parties and anti-capitalist struggles. Indeed, while the Istanbul Convention protects women against family violence, the family/household is also a labor process for women. As Silvia Federici puts it, in the capitalist system, the kitchen is a micro-factory. The beginning of the production line is the kitchen, the end point is the factory or other places of production. Because it is in the kitchen or in the house that labor power, which is the only/indispensable commodity for capitalism, is produced and reproduced. If women are beaten and killed by men in this unit of production, in the first link of the production chain, the struggle against this must be one of the most central agendas of the anticapitalist struggle.

Moreover, the subordination of women is a form of patriarchal oppression as well as a class strategy of capital. Consider Turkey’s current caring crisis. For women, the state’s massive withdrawal from the role of caring and social reproduction means an intensification of the exploitation of unpaid labor or the inability to participate in paid work. And it makes women more economically dependent on men and more vulnerable to male violence. This shows the need for a socialist feminist struggle centered on caring and SRP in Turkey. As a matter of fact, the state withdraws from the responsibilities of caring and SRP by relying on women’s acceptance of being confined to the home, and if they refuse, they will be forcibly confined by men in the home; in short, by relying on capitalist and patriarchal mechanisms of consent and coercion. This is easily forgotten when women perform caring and SRP services free of charge and unseen by anyone. But unfortunately, disaster capitalism does not stop. The contradictions of the SRP come to the surface in crises where even women cannot fill these gaps. When there is a pandemic, we see that the Public Health Department is hollowed out; when there is an earthquake, we see that the Red Crescent is hollowed out.

Therefore, in the midst of such a deep caring crisis, it is imperative that we pay attention to the state’s withdrawal from caring and SRP services and how the lack of access to these services affects women’s care burden and participation in paid work, and make this a necessary element of class struggle. In other words, we have to remind the state of its duty and responsibility to care, not limited to times of disaster, and build a class struggle for its continuity. Or we have to remind the capital of the exploitation of unpaid labor behind the workers’ ability to walk through the doors of that workplace in good health every day and demand compensation for it. And this is only possible through a socialist feminist struggle.

In conclusion, defining labor and the working class beyond the wage contract and the perspective of social reproduction offers us a wide spectrum of class struggle. This is crucial in the neoliberal era, when capital accumulation is attacking nature, women, and the exploitation of cheap labor of different ethnic groups harder than ever before. And it is even more important in the 2020s, when the capitalist system based on the production of life is producing mass death. Therefore, it is more important than ever to fight on every front against the capitalist patriarchy that attacks our lives on every front. Disaster capitalism has shown that these fronts include our paid work, our right to healthy food, our right to healthy housing, our right to clean water, our right to have a say over our bodies… all of those. And it is more necessary and urgent than ever to fight against the capitalist patriarchy that produces mass death, in each of these areas.

For the original in Turkish / Yazının Türkçesi için:

Translator: Gülcan Ergün

Proof-reader: Müge Karahan

[1] The first draft of this article was presented on March 4, 2023 at the conference titled “The Turkey Model of Labor” organized by the Scientific Committee of the Workers’ Party of Turkey. Many thanks to my dear friend and comrade Deniz Ay for her valuable suggestions and contributions to earlier versions of this article.