« Istanbul is working to protect its neglected structures while providing arts and culture spaces for the public » reports Andrew Wilks in Al-Monitor.

Behind a yellow tarpaulin on Istanbul’s Istiklal Avenue workers are painstakingly restoring a 123-year-old apartment building as part of an ambitious project to revitalize the city’s vibrant architectural heritage.

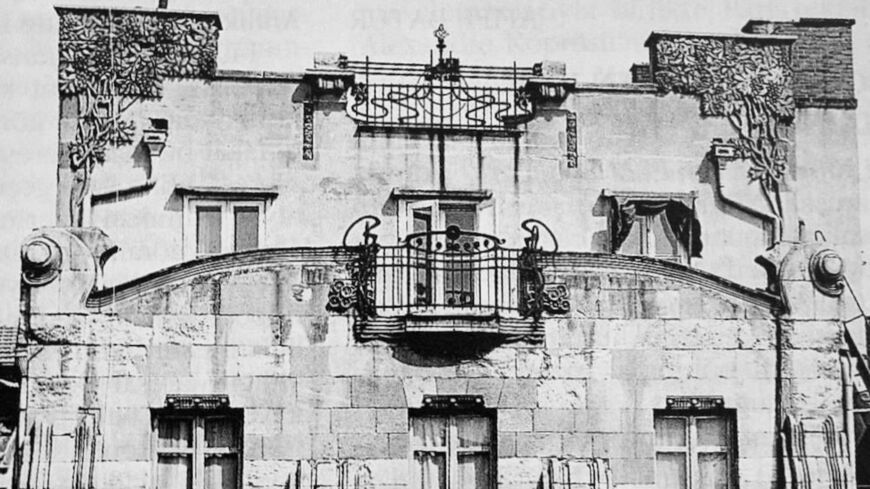

The Botter Apartmani, designed by Italian architect Raimondo D’Aronco, was the first Art Nouveau building of the Ottoman Empire when it opened at the beginning of the 20th century. In recent decades it has been neglected and allowed to slip into disrepair, its roof crumbling and its walls home to pigeons and stray cats.

The building, also known as Casa Botter, is one of the city’s 32 major restoration schemes due to be completed next year. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality also has hundreds of other projects underway. The plan is to open these buildings to the public as arts and culture venues while also maintaining Istanbul’s heritage.

In Beyoglu, the district that has Istiklal Avenue at its heart, respect for the neighborhood’s structural history has fallen victim to rampant commercialization. Corporations buying up fading 19th century edifices tend to overlook architectural treasures as they convert the buildings into shopping centers.

Across the road from the seven-story Botter building stands the Narmanli Han, which originally served as the Russian Embassy from 1831.

When it reopened in 2018 after two years of work there was no sign of the building’s original stone and wood construction and the trees and grass of the central courtyard had given way to grey slabs.

“Beyoglu’s become a very commercial area and rents are very expensive and there’s nothing for the general public,” said Ozan Sakar, director of the municipality’s cultural diplomacy office. “Before we lacked spaces for open events for people to do whatever they want. We believe in collective decision-making. We will just open the space and let people use it as they want.”

The Botter building was built for Jean Botter, a Dutch tailor to Sultan Abdulhamit who then turned his hand to selling European fashions from a store on the ground floor while living with his family upstairs.

A stairway around the second elevator — the second to ever be installed in Istanbul (the first being in the Pera Palace Hotel) — leads to a roof terrace with panoramic views of the Bosporus, the Golden Horn (also known as the Halic) and the Ottoman mosques of the Fatih district.

The restoration team is retaining as many original features, such as the cast iron elevator and wooden doors, as possible so that when it opens as a design center and public space, its links to the past will be featured.

One central aspect of Istanbul’s history, in particular around Beyoglu, is its ethnic mix. This history is evident in the Botter building as restorers have removed paint and wallpaper to reveal old Greek-language newspapers plastered below.

“Beyoglu has always been very international and cosmopolitan and we want to keep that spirit,” Sakar said. “Our approach is to bring out the old industrial and cultural heritage of Istanbul because people forgot how cosmopolitan Istanbul was. We keep building new things but we forget our history.”

The city’s industrial heritage is emerging at other sites undergoing restoration, such as the office building above the Tunel funicular known as Metro Han, the Halic Shipyard and the Feshane, a former factory of the fez headgear adopted throughout the empire in the 19th century. The municipality plans for the Metro Han, formerly the officers of the city’s bus company, to be opened as a cultural center.

The shipyard on the Golden Horn, founded by Sultan Mehmet II following the conquest of Istanbul in 1453, will become an art museum while maintaining its role in building and repairing the municipality’s fleet of ferries and sea taxis.

The Feshane on the other side of the Golden Horn will be one of Istanbul’s biggest arts and culture centers. With the shipyard, will form part of the Halic Cultural Valley and be linked by tram to Eminonu ferry terminal.

The municipality, control of which swung to the opposition Republican People’s Party in 2019, hopes to showcase Istanbul as an international city through art, culture and design, in line with its status as a UNESCO City of Design since 2017.

Mahir Polat, deputy general secretary for the municipality, whose responsibilities include culture and heritage programs, described the restoration sites as “treasures of all humanity, not just Istanbul or Turkey” and said they would provide “space for freedom of speech and freedom of expression.”

“Public spaces are very important for us and we are aware that Istanbul has a problem of spatial arrangement,” he said. “We are aware there are many historic places that can be used as public spaces. They could be the focus of our cultural and social life in the future.”

The vision has the full backing of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu.

“A society that feels, lives and remembers its past memory looks to the future with more hope,” he said in July. “There are many events in the past of this city and this country that will make us look to the future with hope.”

Al-Monitor, December 1, 2022, Andrew Wilks