“Coulisse: Hagop Ayvaz, A Chronicler of Theatre” and the personal archive of Hagop Ayvaz

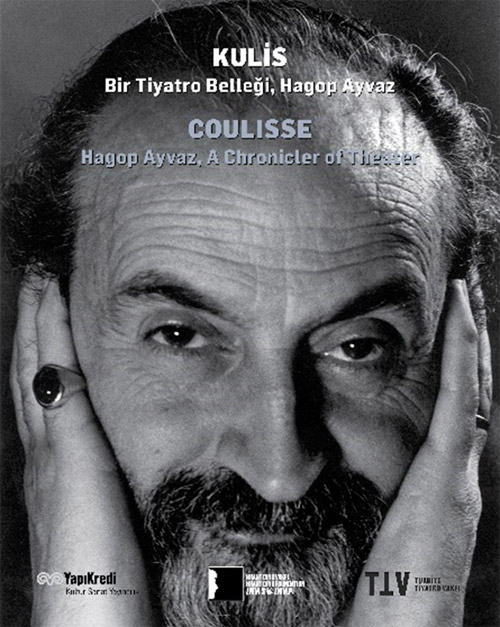

In Istanbul, the exhibition “Coulisse: Hagop Ayvaz, A Chronicler of Theatre” opened a new era in the history of theatre in Turkey. Hagop Ayvaz was a prominent Armenian actor of Istanbul, writer and publisher. This exhibition is drawn from his personal archives, its title is inspired by Ayvaz’s theater and cinema periodical Kulis (Backstage) which was published between 1946 and 1996. Kulis is the longest published theatre review in the history of Turkish Republic.

Making his archives and all the issues of Kulis accessible for the public is a turning point for the history of performing arts of Turkey. This exhibition featuring various content on the Ottoman and Turkish cultural and social life, spanning from the mid-18th century until the first years of the 2000s, has already taken its place among the primary sources as a “source must be referred to” for everyone working on these areas.

Hagop Ayvaz was born in Yenikapı, Istanbul in 1911 and debuted on stage in 1928. After writing about theater at various periodicals, he founded the Kulis magazine in 1946. After 1948, he started traveling abroad for Kulis and reached more readers and writers in many countries of the Middle East as well as Armenia and Greece. In 1996, he published the last issue of his five-decade-old magazine which received countless awards in Turkey and abroad. He received the 1997 Press Service Award of the Writers Union of Turkey and 2005 Honorary Award of the Theater Critics Association of Turkey. He died on September 29, 2006 and was buried at the Şişli Armenian Cemetery (a longer biography can be found at the end of this interview).

The exhibition and Mr. Ayvaz’s archive is made available to the public through the web site of Hrant Dink Foundation..

The exhibition is the result of a collaboration with Yapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing and Theatre Foundation of Turkey, Hrant Dink Foundation. The curators are – Banu Atça, Esen Çamurdan ve Kevser Güler

This interview with the curators is conducted by Ayşan Sönmez – PhD student at the French Geopolitical Institute of Paris 8 University.

Ayşan Sönmez: You have just completed a project long-awaited by the historians and theater researchers working on the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. It is a sophisticated project covering various areas including performing arts, cultural history, urban history, history of everyday life, and so on. As you well know, there are gaps in the cultural history and social history of Turkey as well as the Ottoman Empire. Filling these gaps and revealing a realistic picture require access to works written in languages other than modern Turkish, and refer to every segment of the society that constitute the real fabric of the society. It is important to access resources written in Arabic, Armenian, Greek, Turkish, and those written in the Ottoman alphabets, as well as English, French and Italian resources. Making Hagop Ayvaz’s personal archive and Kulis magazine accessible in Turkish, Armenian and English is unbelievably valuable in this sense.

This was a project that has been on the agenda of the Hrant Dink Foundation for a long time. It has come to life this year with the collaboration of three institutions: Hrant Dink Foundation, Yapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing, and Theatre Foundation of Turkey. Could you tell us a little bit about how collaborations were established, and the process developed?

Banu Atça (Hrant Dink Foundation): When Hagop Ayvaz passed away in 2006, he donated his archive to the Agos newspaper, an Armenian-Turkish magazine founded by Hrant Dink in 1996. The archive was preserved carefully by Agos for a long time, then it was handed over to the Hrant Dink Foundation (HDF) as part of a project aiming to make it accessible to the public. HDF was responsible for the project design.

For a long time, digitalization and categorization of the personal archives and the Kulis magazine have been carried out. Then, we made a content classification and saw that certain topics came to the fore such as the city, theater venues, daily life, culture industry, and social memory. We had a concentration of documents and information on the history of culture and theater covering 150 years, from the late 1800s to the Republic years, even to the early 2000s. We noticed that we can re-read the history through an archive. Therefore, reconsidering the history of Turkish theater with an exhibition has become another topic. And, of course, Hagop Ayvaz’s experience as an archivist and his life was another main topic. In this context, we have also reviewed the history of the Armenian theater during Turkish Republic.

We know that Hagop Ayvaz had a dream to make use of his archive as part of a museum. Therefore, we made a call to Theatre Foundation of Turkey, which we know is also a museum project. We also made a call to Yapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing, because their place was right spatially in terms of the exhibition venue. Besides, they have experience and knowledge in exhibitions. We wanted this project to be intertwined with the city and to have high visibility. Yapı Kredi’s location is in the Galatasaray Square of İstanbul, right in the city center. Both institutions gave positive responses to our call.

There is a whole team behind this effort, rendering it a truly collective work: First and foremost, archive team, Armenian-Turkish translators, the Agos employees, who gave us unfaltering support; the Hrant Dink Foundation staff, editors, advisors whom we turned to at every challenge, of course Aras Publishing House; people who contributed to the oral history work; and many other individuals. We truly enjoyed this collective effort, which gave us a fresh breath of air so to speak. When Mr. Ayvaz described his archive as “a heaven on the earth”, he was not exaggerating a bit.

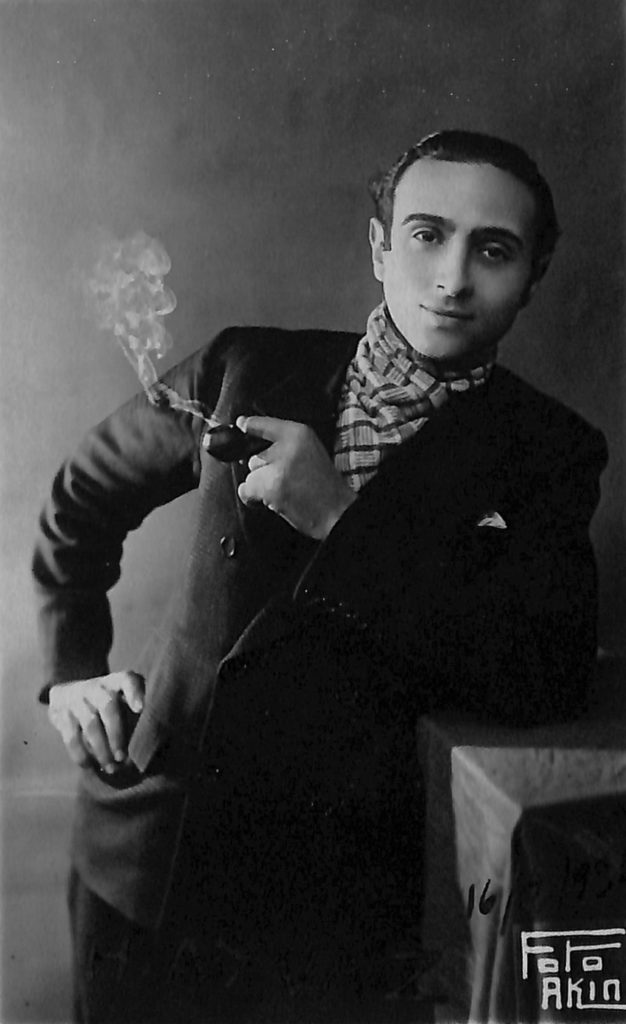

Photos: Hagop Ayvaz (1935); Bedros Mağakyan in Aleksandr Şirvanzade’s play Çar Voki [Evil Spirit] as ‘Kij [Mad] Taniel’ (1920); Hagop Ayvaz (images are provided by the curators).

Kevser Güler (Yapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing): This invaluable offer for collaboration was very welcomed by Yapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing, which has been organizing exhibitions unfolding the history of culture and arts in Turkey from various perspectives. This institutional collaboration brought about a curatorial collaboration: Banu Atça of Hrant Dink Foundation, Esen Çamurdan from Theater Foundation of Turkey, and me fromYapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing, shared the curatorial responsibilities of this exhibition based on the Hagop Ayvaz Archive. Our journey to anticipate this exhibition began in the first weeks of 2020. In the beginning, we had imagined days replete with lengthy conversations around a table or in a room where we could physically analyze the archive content, touch and see it in place; however, with the onset of the pandemic, this became impossible, and we had to explore new methods. The digitalization of the archive, once again through the hard work of the Hrant Dink Foundation teams, helped us step up our work, and by April, the archive materials were fully digitalized and accessible for the exhibition team. On December 15th, when the exhibition was inaugurated, Mr. Ayvaz’s archive was also made available to the public through the web site of Hrant Dink Foundation.

We conducted most of our research on the archive through online dialogue, working in this digital environment. At an early stage, there emerged ideas about the possible sections of the exhibition. We needed to share Mr. Ayvaz’s ventures into theater in one section; then dedicate one section to the Kulis magazine, published for 50 years -a rare example across the world- through Mr. Ayvaz’s ceaseless efforts without any institutional support; and yet another section had to focus on notebooks, posters, photographs and drawings inviting the audience to rethink the birth of performing arts in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, the pioneers of the field, and the ties between this cultural milieu and the city.

Afterwards, Sera Dink came on board to carry out the exhibition design, shaping the graphic language and spatial relations. In this aspect of our work, Mr. Ayvaz once again provided us valuable guidance with the graphic choices he had made in the Kulis magazine. Kulis was a comprehensive publication featuring not only articles on theater and performing arts, but also poems, cartoons, social criticism, sections on popular culture, interviews, announcements, embodying audacity and excitement, and always remaining vibrant. It was published in Armenian throughout these 50 years, yet for a very brief period it also had supplements in Turkish between 1954-1956, upon request. A still valid perspective on history upheld by Mr. Ayvaz throughout the life cycle of Kulis, figured among the main sources of inspiration for the exhibition. We pondered at length on how to approach the materials on view as both historical documents and current day news items. We considered it crucial to refrain from any action that risked transforming the archival materials on display, whether a notebook, a poster, or a letter, into inscriptions, into self-enclosed objects of symbolism and nostalgia -exactly what Mr. Ayvaz avoided in Kulis magazine. We realized that was what he drove home in almost every issue of Kulis without exception: While insisting upon the necessity to interpret, explore, question, interrogate and pen history, he never postponed reflecting upon what today is and can become, thus multiplying this today, and presenting the scope of today in all its complexity: putting forth new scenes, modes of action and manners of coexistence; and while doing so, imagining a future horizon with an almost infinite belief in the possibility of surpassing the existing conditions. Accordingly, the graphic language and spatial relations within the exhibition invite the audience, on the one hand, to establish a direct relationship with what lies right before us, through our eyes and gaze; and on the other hand, as what is immediately visible recedes to the background, they move towards resuming a historical encounter -just like the bond we may establish with a notebook or book. And exactly in between, between the image and the text, between what Mr. Ayvaz’s archive points to and what it renders visible, theater stages are founded, the magazine is published, the audience gathers around, plays are staged, and the stories of those who labor and struggle come on view -all the while drawing upon the bonds forged between theater, and the gaze, space, text and word.

Another aspect we decided upon at a very early stage of the exhibition’s design was to make it trilingual. As a result of diligent editorial efforts, the exhibition has now opened its doors as a trilingual exhibition in Armenian, English and Turkish. It thus invites the audience to rethink what was rendered invisible by the dominant historiography in the context of the Ottoman and Turkish history of culture and arts, while pointing out the diversity and sophistication of the sources at hand. It especially draws attention to sources that may be accessed and explored in the Armenian language.

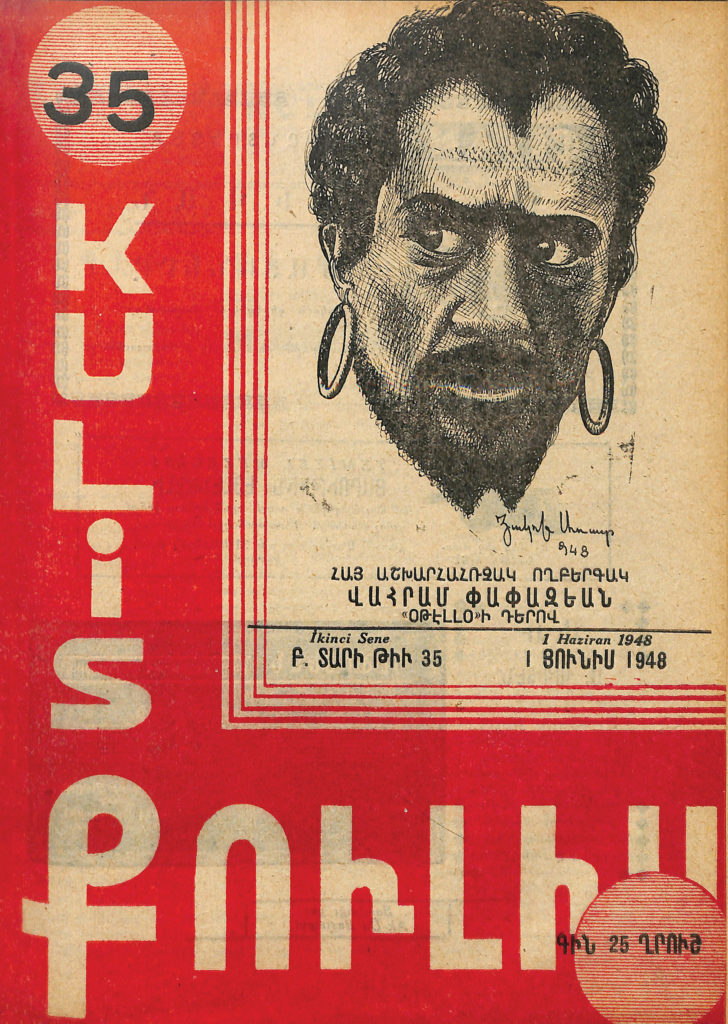

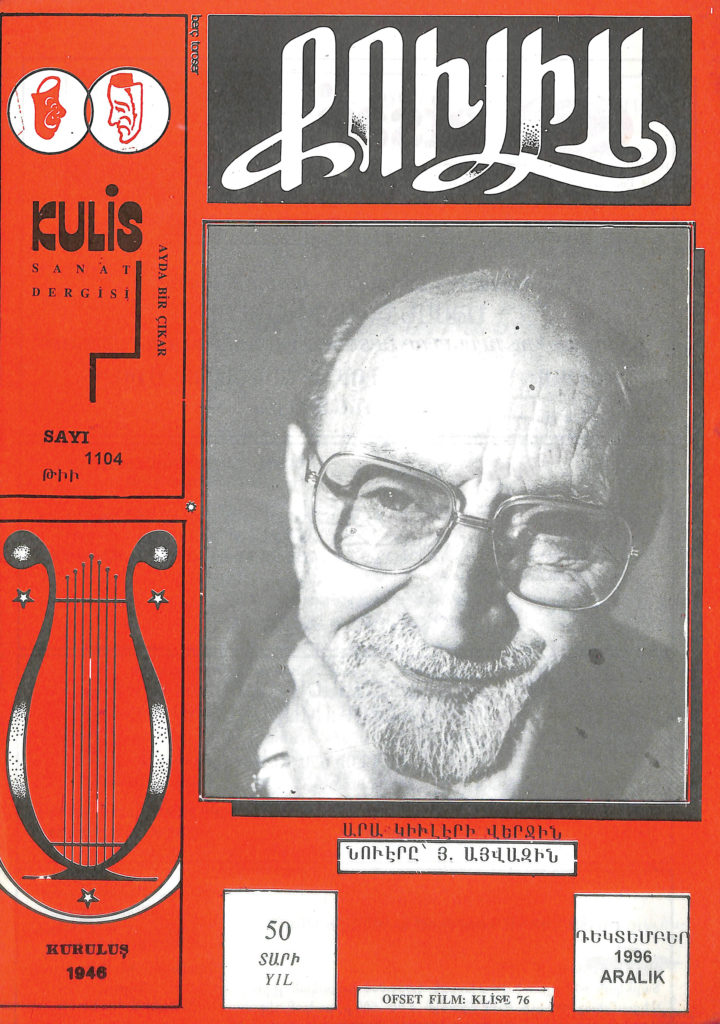

Photos: Cover of Kulis’s first issue (15.12.1946): Viviane Romance (real name Pauline Ronacher) in La route du bagne released in 1945; Kulis 35 (1.6.1948) Vahram Papazyan; Kulis 1104 ( December 1996) (images are provided by the curators).

Banu Atça: The Kulis documents the theater activities between the years 1946 and 1996: theater critiques, news broadcast on Kulis Radio, ads and announcements, and posters published in the magazine provide us information on which plays were staged by whom and where in each year. Furthermore, the magazine has regular sections on the prominent players and theater companies in Turkey’s theater scene, such as “Faces from the Theater World” and “Theater”. Here we come across biographies and theater articles on thespians such as Hagop Vartovyan and Gedikpaşa Ottoman Theater, Benliyan (Turkish) Operetta, Orient Theater, Armenian Drama Company, Atamyan Theater, the Mnakyan repertoire, Ottoman Drama Company, prominent actors such as Ahmet Fehim, Hazım Körmükçü, Bedros Baltazar, Selim Naşit, Aşot Madatyan, Muhsin Ertuğrul, the Ferah and Darülbedayi actors, not to mention Arusyak Papazyan, Yeranuhi Karakaşyan, Knar Hanım, Eliza Binemaciyan, Afife Jale, Jerfin Elmas and Lusi Tokatlı.

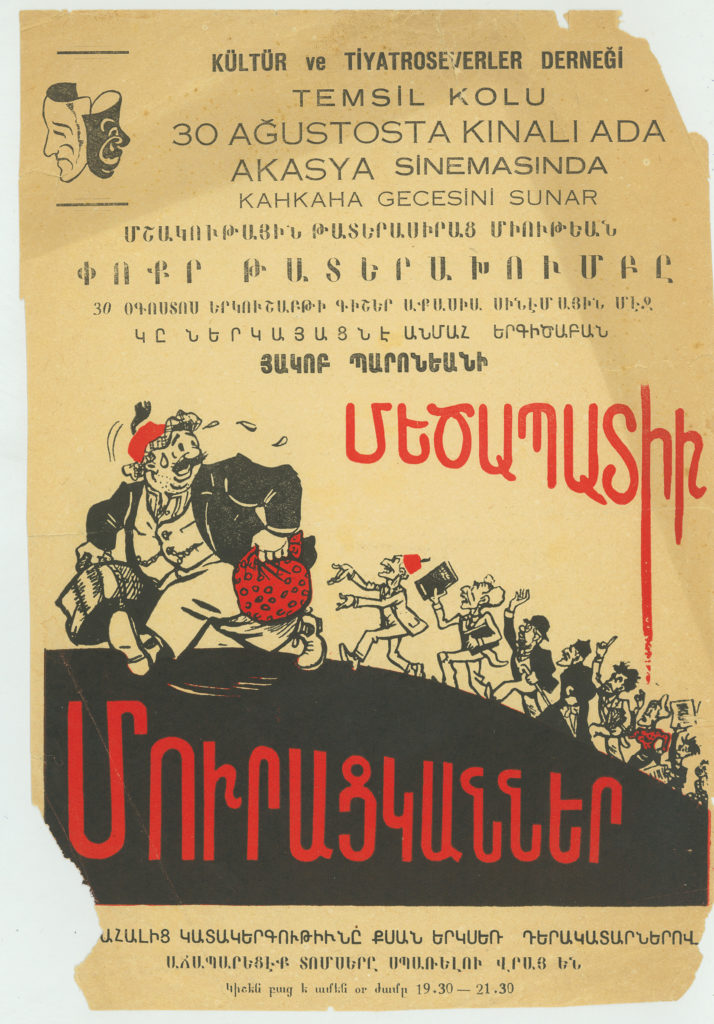

There is one more thing to add. One of the most important aspects of the theater is, of course, the audience. In addition to many people who work for the theater on or behind the stage, the theatre venues also provide information on the audience’s profile through the languages of the plays. And also, information about the number of the audience, audience’s interests, and the daily life of the city dwellers, etc. When we look at the flyers and timetables, we can see that there was an intense staging program both in Beyoğlu and Direklerarası, which are considered as the two theater centers of Istanbul historically. We know how many playhouses were out there, and their capacities. We know that the plays were staged in Armenian and Turkish. We come across posters in Greek, French, Armenian and Ottoman, too. It means that the plays appealed to those who knew these languages. This gives information about the audience profile. It is an inspiring archive in terms of being able to rethink about the possibilities of making a pluralistic theater.

This exhibition is based on a personal archive. What is the importance of personal archives in the culture and social history of a country?

Esen Çamurdan (Theatre Foundation of Turkey): Well, considering the huge amount of material that has been revealed with this exhibition, I can say that, this exhibition shows the value of keeping an archive and sharing it with the public. Archives and archiving are really important, especially in countries like ours, the ones suffer from memory loss. An archive is a “memory storage” no matter what kind it is, and makes people find what is forgotten and/or has been made us forget. As in the example of Hagop Ayvaz, archives that are focused specifically on a person and a subject, and a particular theme, are also a form of resistance. The people like Hagop Ayvaz want some values and experiences not to be forgotten, they try to make them permanent, they are persistent, they want to leave a mark on the future.

Personal archives fill some of the historical gaps that we have noticed or not, or at least leads one to question, if not, to think. In parallel, the archive creates the social and cultural background that has a strong impact on the process of shaping social identities; it affects the way official history is perceived and understood.

The “indispensability” of sharing the archive with the public, the importance of disclosing it to the public shows itself at this point. We can go even further and argue that an archive, like a living organism, increases its value, increases its size when it confronted with someone else’s view and interpretation. This is an ever-changing and evolving relationship. And this exhibition once again showed that sharing an archive with the community is a sacred duty, an unbelievably valuable cultural and historical service, if it is not collected for a private work.

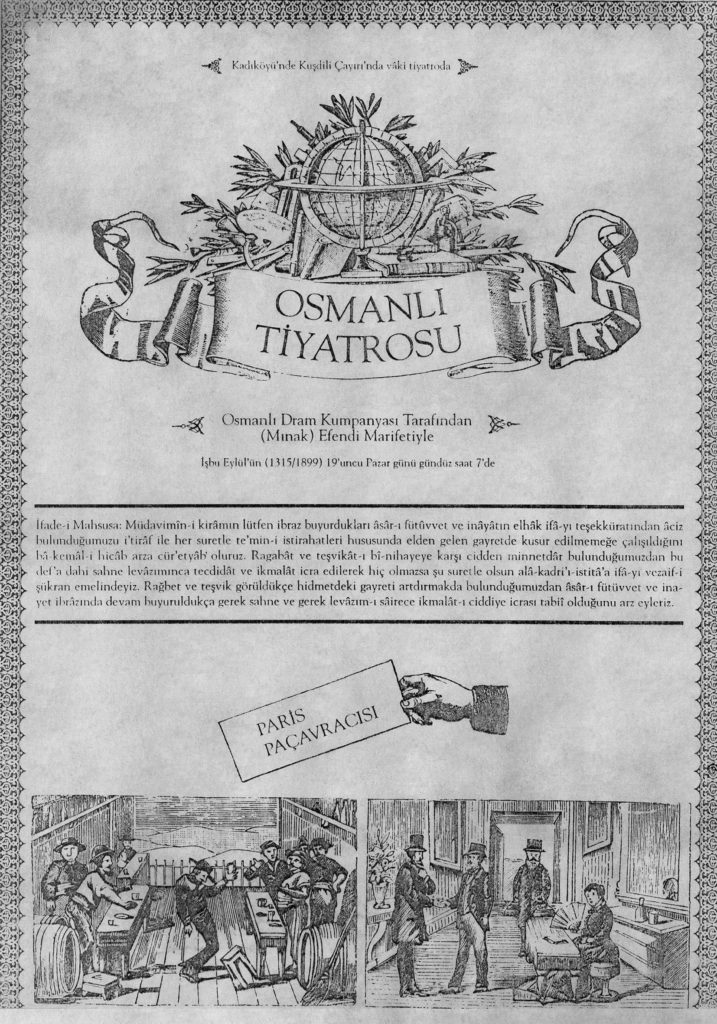

Photos: Poster of the play Paris Paçavrası [Rags of Paris] staged by the Ottoman Drama Company led by Mardiros Mnagyan on September 19, 1899 at the Kadıköy Kuşdili Pastures; Pokr Taderahump [Small Theater Company], Medzabadiv Muratsgannerı [The Honorable Beggars] (Kınalıada Akasya Movie Theater) (images are provided by the curators).

Its reach and implications are very extensive. Obviously, everyone working on Turkey and Ottoman Empire should refer to this archive. Are you planning to digitize the personal archive and the Kulis ?

Banu Atça: Simultaneous with the exhibition, Hagop Ayvaz archive has become accessible digitally. We digitized all images, including photographs, posters and cartoons. 1104 issues of Kulis magazine were digitalized with their covers, captions and content pages. It was made available in Turkish, Armenian and English. The content is still uploading. At the same time, there are nearly 600 printed and manuscript theater plays in the archive. This is one of the most impressive parts of the archive: the copyrighted plays. There are adaptations, translations, staging of the classics, Turkish plays with Armenian letters etc. The cataloguing of these notebooks and printed theater plays has been completed, and there are samples in the exhibition. The archive can be accessed digitally from the Hrant Dink Foundation website.

The period in which the magazine has started to be published is important. It’s been told how a group of people got the permission from the government to do theater in Armenian. You know the story, too. After the Second World War, Suren Şamlıyan, founder of the Marmara Gazetesi, Mardiros Koçunyan, owner of the Jamanak Gazetesi and Hagop Ayvaz visited Ankara. During their meetings with the government, Suren Şamlıyan asked İsmet İnönü why no Armenian plays were staged (one rumour says that this question was directed at Şükrü Saraçoğlu). İnönü replied that he was not aware of this, that there were no such restrictions and that of course Armenian plays could be staged. This meeting in 1946 is of critical importance for the history of Armenian theatre in Turkey. After this date, the “restrictions” on Armenian theatre were lifted and associations began to stage plays in Armenian. Hagop Ayvaz began to publish Kulis, which was to remain in circulation for 50 years, making it Turkey’s longest running theatre magazine.

Banu Atça:It is true. There is a de-facto ban between 1923 and1946. Performing theater in languages other than Turkish was prohibited. It was about the unification and nationalization of the multilingual theater environment. During this period, either theater was not held, or it was made in Turkish, or theater was organized within the body of small associations. Hagop Ayvaz started publishing the magazine after this ban was lifted in 1946 and says, “This ban was lifted for us because we started to hear theater in Armenian again, and that meant to find news for [our magazine] again.”

After that, Aşot Madatyan translated Faruk Nafiz Çamlıbel’s play “Canavar”(Monster) into Armenian as “Kazan”, and the play was staged by the Stüdyo theatre company.

Banu Atça: Hagop Ayvaz starts making theatre in these days. Shakespeare classics, translated plays, etc. started to be staged again. Kulis magazine, featured on their pages the the people that contributed to the foundation of modern theater in the Ottoman Empire, these theatre companies, starting from the middle of the 1850s,. There is something that should be noted in terms of the personal archive and the Kulis archive. Hagop Ayvaz has always named his own archive as the Kulis archive. Kulis magazine guided us while working on and understanding the personal archive of him. The personal archive made sense to us when we were reading it simultaneously with Kulis. For example, we can understand why certain images were sent from abroad by referring to Kulis.

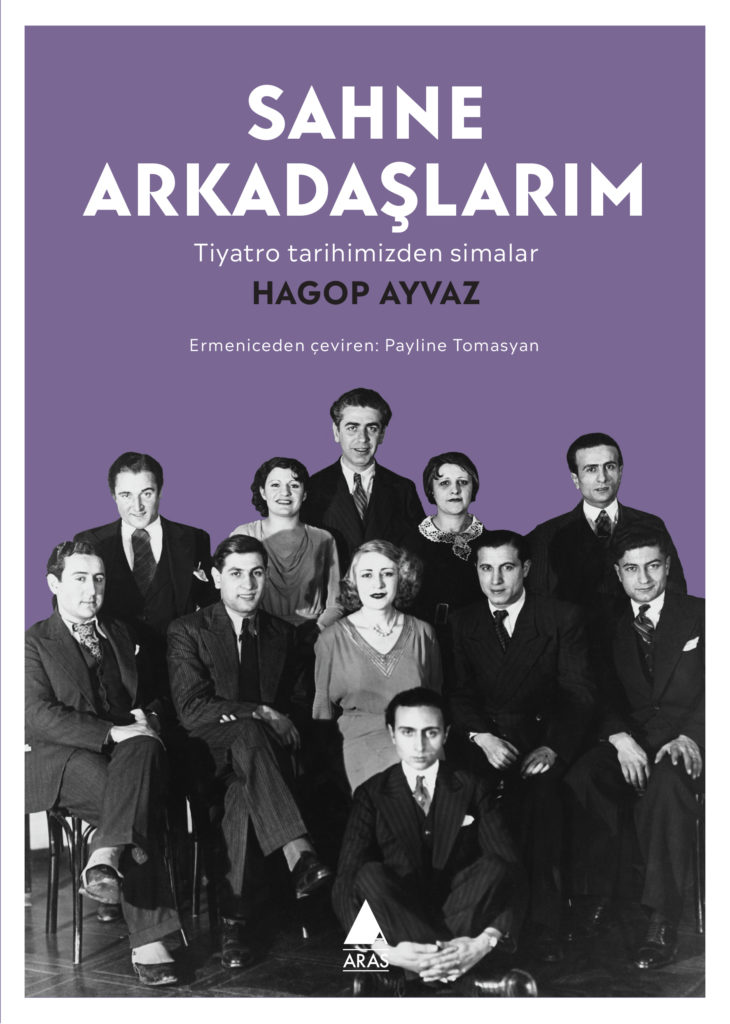

Simultaneously, Aras Publishing House published a book on Hagop Ayvaz: “Sahne Arkadaşlarım – Tiyatro Tarihimizden Simalar” (My Friends on the Stage – Faces from our Theater History) translated and edited by Payline Tomasyan and Rober Koptaş. As Yapı Kredi Publications, you published an English/Turkish, bilingual catalog of the exhibition and the Foundation introduced the theater venues during the İstanbul Theatre Festival 2020via the KARDES application, a personal tour guide in Turkish and English to discover the multicultural legacy and multilayered fabric of Istanbul. The exhibition, personal archive, the catalogue and digitalized documents along with these publications create a more comprehensive picture. Can we talk about them?

Kevser Güler: We published a Turkish/English bilingual catalog of the exhibition as Yapı Kredi Culture Arts and Publishing. Edited by Fisun Yalçınkaya and designed by Hasan Fırat, the catalogue has been published by Yapı Kredi Publications. Available in English and Turkish, the catalogue encompasses a large part of the documents and images on display in the exhibition, an introduction by the curatorial team, articles by Esen Çamurdan, Dikmen Gürün, Nesim Ovadya İzrail and Karin Karakaşlı on Hagop Ayvaz’s passion and archive, personal memories about Ayvaz, Kulis magazine, as well as a biography of Ayvaz penned by Banu Atça. These are further followed by an interview with Hagop Ayvaz, conducted by Berç Noradukyan and Boğos Çalgıcıoğlu in 1987. This interview allows us to learn about the origins of Ayvaz’s love for theater and his subsequent endeavors, in his own words. (https://www.yapikrediyayinlari.com.tr/kulis-bir-tiyatro-bellegi-hagop-ayvaz.aspx)

I would especially like to draw attention to the Hagop Ayvaz Archive, which has become accessible via the website of Hrant Dink Foundation on the first day of the exhibition. (https://hrantdink.org/tr/arastirma/arsiv/190-hagop-ayvaz-arsivi/2855-hagop-ayvaz-arsivi)

The three-dimensional photographic documentation of the exhibition (generally called “a digital exhibition” these days), is accessible on the website of Yapı Kredi Culture Center.

Banu Atça: KARDES application had multicultural tours to introduce historical Istanbul (Click here). A new one came out recently: Beyoğlu theater tour. There are 12 stops here. We have prepared a tour covering the theater buildings in Beyoğlu, Istanbul, starting from the mid 1800’s, during the glorious days of theatre. Among these venues, unfortunately, the only one surviving today is Ses Theater.The stories of many venues such as French Theater, Naum Theater, Orient Theater and Concordia Theater can be heard on the app. This tour can be enjoyed simultaneously with the exhibition. Besides, Aras Publishing has a book: “Sahne Arkadaşlarım – Tiyatro Tarihimizden Simalar” (My Friends on the Stage – Faces from our Theater History). They had compiled and published the articles that have been published in Kulis magazine and Agos newspaper under the title of “Lutsika Dudu” (Mrs. Lutsika) in Armenian before, and now they published them in Turkish simultaneously with this exhibition. We should also thank them.

These are all now accessible to Turkish readers. Considering the number of those who know the Ottoman language or the languages of this land apart from Turkish have decreased dramatically lately, we should thank them.

Banu Atça: As regards the history of Turkey’s theater, we may say that this exhibition enables a reckoning with the formation of modern theater in the Ottoman Empire during the westernization drive of the Tanzimat Era, and the multilingual theater production of that period. In fact, we come across the founding figures and theater companies which have launched and developed modern theater in Turkey, expended immense efforts and weathered a series political hardships. We discover Armenian players and directors such as Güllü Hagop, Mardiros Mnakyan, Arusyak Papazyan, Tomas Fasulyacıyan, Bedros Atamyan, Mari Nvart, Knar Hanım and Eliza Binemaciyan, who have largely marked this period, taking the first steps in modern theater in these lands. Theater venues and plays staged in districts such as Direklerarası, Beyoğlu, Üsküdar and Kadıköy also shed light on the theatrical production of the epoch, the relation between the city and theater, and of course the theatergoers -the sine qua nonof this art.

On the other hand, we can also trace the stages of institutionalization of theater, namely, the establishment of Darülbedayi, which laid the foundation of today’s municipal theater, as well as the conservatory’s faculty members consisting of Armenian and Turkish directors and actors. With the foundation of the republic, we come across the operettas and independent theater companies of the period, while Mr. Ayvaz takes up acting. Afterwards, Armenian-language theater activities are de factobanned and suspended, the field of theater becomes uniform as only Turkish-language plays are staged, and in a sense, the multilingual era in theater comes to a close. After 1946, Armenian-language theater resumes; however, much was lost in the meantime, and Armenian theater is continued only by associations.

Finally, the exhibition also offers a glimpse into a feminist history of theater, and the struggle waged by actresses. Against the historical narrative of the powerful and the masculine, in the exhibition, we have opened up a space for the portraits of actresses in theater history. In the past, Muslim women were forbidden to take the stage, and Afife launched a struggle against that. Neither was the appearance of Armenian women on stage accepted without objection. Violence was employed to prevent women from taking the stage or watching the spectacle; nevertheless the efforts to intimidate or subdue women ultimately came to naught. When we ask ourselves who are the individuals that forged this history, we come across Armenian actresses. The first amateur actress Fanni (Agavni Hamoyan) in 1856; the first professional actress of the theater scene Arusyak Papazyan; the first actress to portray Hamlet, Siranuş (Merope Kantardjian); Mari Nvart who dissimulated her pregnancy to play the Lady with the Camellias and later on died at a young age; the pioneering, master thespians of Darülbedayi, namely Knar Hanım and Eliza Binemaciyan among others. A case in point, when Afife Jale took the stage at the Apollon theater, the person who helped Afife escape from the police was Knar Hanım. We have thus tried to render visible the struggle and solidarity of actresses in the history of theater in Turkey.

The cover of “Sahne Arkadaşlarım – Tiyatro Tarihimizden Simalar” (My Friends on the Stage – Faces from our Theater History). Published by Aras Publishing House in December 2020.

You are right, this is particularly important. I would like to talk about the symbolic meaning of the exhibition. The exhibition is opened in Galatasaray Square of Istanbul. It is an area that has been politicized and criminalized a lot in recent years in parallel with Turkey’s political agenda. It is also the main entertainment and cultural arts center of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. This district is also the multilingual center of the Ottoman past. Ottoman Turkish, Armenian, Greek, Italian, French, and English, etc. It is a part of the city where all the languages of the Ottoman Empire were spoken; people entertained in these languages in the same region. With this exhibition, under such a heavy political agenda, you are reminding us of this past with a 3-language exhibition: English, Turkish and Armenian. I see this as a normalization call, a peace call. You are reminding us of our common past with this exhibition. I find it valuable in this respect. Has the political tension of the country created any obstacles for you?

Banu Atça: Galatasaray Square has been turned into an area of human rights violations, into a police station.For example,since May 1998, however, the Saturday Mothers have faced heavy- handed police repsession. We are, however, committed to a world where pluralistic and participatory co-production is possible.The exhibition in the Yapı Kredi Culture Arts and Publishing’s center presents this option. Ever since the Hrant Dink Foundation was founded, its aim has been to contribute to a pluralistic, multilingual, and multicultural life where everyone lives equally. The foundation has already been built on great pain, with difficulty. It has been one of the missions of the Foundation since the very first day, to remember despite the pain and difficulties, to confront with them, to make new generations think that another way is possible. This project overlaps with this mission. One of the things that created difficulty for us was the pandemic. In addition to political tensions, conducting the work during the pandemic was extremely difficult and we passed through a rough period.

Photo: Darülbedayi’s cast when they performed at the Ferah Theater: Muammer Karaca, Behzat Butak, Hazım Körmükçü, Galip Arcan, Muhsin Ertuğrul, Nurettin Şefkati, Küçük Kemal (Kemal Küçük), front row, second from right Neyyire Neyir Ertuğrul. Click here to access the archive and detailed information (images are provided by the curators).

The pandemic broke out immediately after the project call was made in March. We had to stay at home, we could have easily given up but Hagop Ayvaz’s resilience has impressed and inspired us tremendously from the very beginning. He achieved to publish his magazine uninterruptedly for 50 years despite all kinds of difficulties; and the theater could not be a means of livelihood for him, so he always had to do extra work to survive. It is a 95-year-struggle, 70 years of acting and writing. It was this bellicosity that inspired us the most. We said that we would not give up, and continued with this belief in the pandemic, during the days of curfew. It was difficult for the three different institutions to try to open a physical exhibition through an application called Zoom, which has entered our lives with the pandemic, and to meet constantly online to organize a physical archive. There is a very crowded team behind this project. Everyone was so determined.

Such an exhibition would lead to similar works focusing on “memory loss” issues as you raised.

Esen Çamurdan: I think it would be a good example in every respect. The interest and excitement of the press and the public is high. It may inspire some institutions to organize “archive-exhibitions”, and such events have not been of interest until today. Likewise, archivists and collectors can also take up this job. Moreover, it can mobilize many researchers or cause new exhibitions to be opened. The exhibition provoked people to learn, research and question.

Will there be online tours during the pandemic?

Kevser Güler: Based on the course of the pandemic, during 2021 there will be organised several online tours. “Coulisse: A Chronicler of Theater, Hagop Ayvaz” is on view at Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat until February 21st, every week day from 10:30 to 18:30. It is currently closed during the weekends due to the lockdown. Once the lockdown ends, Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat’s exhibition spaces will open their doors to visitors every day of the week, as was previously the case. Any changes due to the pandemic will be announced via the web sites and social media accounts of Hrant Dink Foundation, Yapı Kredi Culture, Arts and Publishing and Theater Foundation of Turkey.

***

Hagop Ayvaz was born in Yenikapı, Istanbul in 1911. His stage debut was in 1928 at the Narlıkapı Şafak Theater as an extra in the operetta Jaghatsbanin Aghchige [The Miller’s Daughter]. His first lead role was in the The Trail of the Serpent at the Beyoğlu Yenişehir Garden Theater in 1930. He wrote columns for Jamanag, Turkiya, Gavroş and Nor Or between 1935–1946. Together with Zareh Arşag and Nazaret Donikyan, he co-founded the Kulis magazine in 1946. Between 1947–1950, he organized special nights for Kulis where Armenian and Turkish artists shared the same stage. After 1948, he started traveling abroad for Kulis and reached a wider audience and writers in many countries of the Middle East as well as Armenia and Greece. Between 1954–1956, he published Kulis in Turkish with the support of the Istanbul Operetta Association. He assumed the leadership of the Stage Troupe of the Esayan School Alumni Association in 1960 and made his directorial debut with Galip Arcan’s Rica Ederim Kesmeyiniz [Please Do Not Interrupt] and founded Pokr Taderhump [Small Company]. He started writing for his memorable column Lutsika Dudu [Mrs. Lutsika] in 1968. In 1996, he published the last issue of his five- decade-old magazine Kulis, which received countless awards in Turkey and abroad and started writing for Agos in 1997, which lasted until 2006. He received the 1997 Press Service Award of the Writers Union of Turkey and 2005 Honorary Award of the Theater Critics Association of Turkey. He died on September 29, 2006 and was buried at the Şişli Armenian Cemetery (Source for the biography: Hrant Dink Foundation website).