Summary

« In June 2021, Eşref Akoda shot dead his 38-year-old wife Yemen outside her home in the central Anatolian town of Aksaray. Prior to this lethal assault, courts had on four separate occasions issued preventive orders aimed at keeping Eşref away from Yemen after he harassed her when she filed for divorce. A lawyer for the family said that Eşref Akoda had approached and threatened his wife at least twice, violating the third and fourth preventive orders, but that on those occasions the court had not imposed any of the available disciplinary sanctions on him, such as a short period in detention, due to a “lack of evidence”. The prosecutor also declined to bring criminal charges against him, even though Yemen’s lawyer had filed complaints with the prosecutor’s office » reports Human Rights Watch.

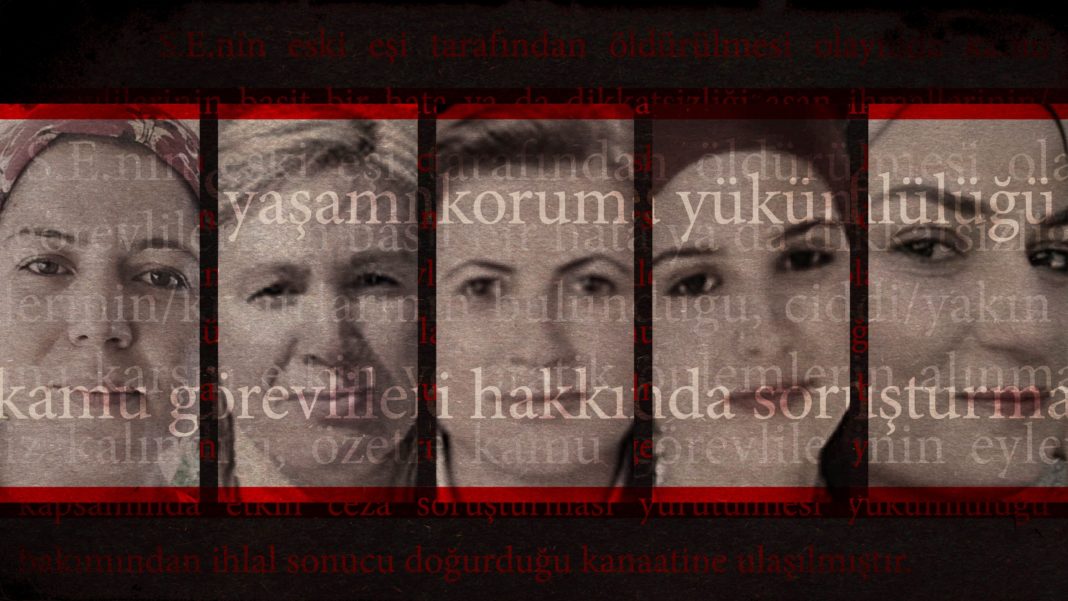

Ayşe Tuba Arslan died on October 11, 2019, of injuries inflicted by her former husband Yalçın Özalpay using a meat cleaver and a knife. Arslan had lodged 23 complaints with the police and the prosecutor’s office against her former husband between 2018 and 2019, obtaining four preventive orders which he breached repeatedly without consequences. The harshest sanctions he received for repeated assaults and threatening behavior were a form of suspended prison sentence and fines. Özalpay avoided detention for violating the preventive orders because Arslan was allegedly unable to produce proof of the violations.

S.G. was arrested on September 6, 2019, for attacking and stabbing his former wife Merzuka Altunsöğüt, injuring his daughter and attacking his son who was 15 years old at the time. On the same day a court ordered his release despite the fact he was violating the conditions of his parole, having been convicted of a previous knife attack on his ex-wife in 2013. After his daughter highlighted the case on social media decrying the court’s decision, the authorities took steps to have him remanded to pretrial detention. S.G. was convicted of attempted murder and at time of writing was serving a prison sentence. But with the possibility of his early release on parole looming, Altunsöğüt and her lawyer were anticipating the threat he may pose to her once again.

These are among the starkest examples of the Turkish state’s failure to provide effective protection from domestic violence, to assist survivors of domestic violence or to punish perpetrators of attacks on women, even when the perpetrator is a serial abuser. Around four out of ten women in Turkey say they have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by husbands or partners at some time during their lives, according to government studies from 2008 and 2014. Women’s rights groups and independent media regularly record hundreds of femicides in Turkey every year. Turkey’s Interior Ministry, in a report to a 2020-21 parliamentary commission looking at the causes of violence against women, provided fluctuating numbers of femicides over the past five years, the lowest being 268 femicides in 2020, with the figure for 2021 having risen again to 307.

This report examines the failure of the Turkish authorities to adequately protect women from violence, prevent the recurrence of violence, and hold perpetrators to account. The report comes 11 years after a 2011 Human Rights Watch report which provided a wide-ranging perspective on the problem of family violence in Turkey at that time.

The present report tackles the use of preventive and protective cautionary orders issued by courts and law enforcement officials under Turkey’s 2012 Law to Protect the Family and Prevent Violence against Women (Law No. 6284). Law No. 6284 incorporated many aspects of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combatting Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (known as the Istanbul Convention) into Turkey’s domestic law and remains in force despite Turkey’s withdrawal from the convention in 2021.

Under Law No. 6284, victims of domestic violence can apply to the police or to the public prosecutor at the courthouse for preventive cautionary orders which can include a range of measures aimed at compelling perpetrators of domestic violence to stop all forms of harassment and abuse, including by barring them from approaching and contacting the victim. Victims are also entitled to apply for protective orders to secure various forms of physical protection, including immediate access to a shelter or short-term accommodation if no shelter is immediately available, the possibility of calling in police protection on demand, and, in some cases, the opportunity to have their identity and whereabouts concealed. Courts issue cautionary orders for a specified duration of up to six months. Victims may apply for them to be renewed. Perpetrators can be sanctioned with short periods of detention (zorlama hapsi) or be required to wear an electronic tag if they breach the terms of preventive cautionary orders.

It is crucial that authorities responsible for implementing protective measures for women from violence do so in coordination with social services responsible for women’s access to housing, health care, employment, and education for children. An examination of all these dimensions falls outside the scope of this report.

This report reviews 18 cases of domestic violence during the period 2019 to 2022, with one case from 2017, in which women lodged complaints with the police and prosecutors concerning violence by current or former spouses and partners. It shows that while police and courts are issuing preventive and protective cautionary orders, failure to ensure they are observed leaves dangerous protection gaps for women if not rendering them meaningless. Courts often issue cautionary orders for far too brief periods, and the authorities fail to undertake effective risk assessments or monitor the effectiveness of the orders, leaving survivors of domestic violence at risk of ongoing – and at times deadly – abuse. Some perpetrators breach the terms of preventive cautionary orders without penalty. For those who are subject to criminal prosecution and conviction, it often comes late and the penalties are too little to constitute an effective deterrent. In the most severe cases, six examples of which are included in the report, women have been murdered even though the risk they faced was known to the authorities and perpetrators had been formally served with preventive orders.

The Interior Ministry’s own figures presented to a parliamentary commission on violence against women demonstrate that in around 8.5 percent of cases of women killed between 2016 and 2021, the woman had been granted an ongoing protective or preventive order at the time of her murder. In 2021, 38 of the 307 women killed were under protection, the highest number over the previous five-year period for which figures are recorded.

While penalties for men who murder women have risen over the years, there needs to be more focus on the failure of the authorities to prevent these murders. There should be clear processes for investigating and holding to account public authorities in cases where they have not exercised due diligence in preventing and protecting victims of domestic violence.

In this respect, a judgment of Turkey’s Constitutional Court published in December 2021 breaks new ground. In the case of T.A. (no. 2017/32972), the court identified a catalogue of state failures amounting to violation of a woman’s right to life in substantive and procedural terms. The court determined that public officials, prosecutors, and judges had failed to take the necessary steps to protect a woman who had lodged multiple complaints with the authorities before she was killed by her former husband.

Some cases documented in this report show that preventive measures can help protect survivors of domestic abuse from further violence, but only if such measures are implemented effectively.

Poor data collection prevents authorities and the public from having a solid grasp on the scale of domestic violence in Turkey or the gaps in implementing protection which contribute to ongoing risks for victims. There are discrepancies in the data on the number of protective and preventive orders issued over the past five years but the available data shows that the number of orders being issued is increasing. The Justice Ministry presented a 2021-22 parliamentary commission with data on the number of individuals for whom courts issued protective and preventive orders as follows:

| Year | Number of individuals receiving preventive orders | Number of individuals receiving protective orders |

| 2016 | 139, 218 | 1,801 |

| 2017 | 151,715 | 2,552 |

| 2018 | 181,072 | 4,648 |

| 2019 | 195,242 | 5,725 |

| 2020 | 244, 985 | 7,293 |

| 2021 | 272,870 | 10,401 |

Government data does not provide information about implementation.

In cases of domestic violence in Turkey, including those reviewed in the report, women, their daughters, or their lawyers often resort to appeals via social media, and sometimes in print media or television, in an effort to trigger action by the authorities. While successful in some cases, the need to resort to such tactics is an indictment of the authorities’ failure to provide protection or to respond adequately to the risks victims face.

Between the publication of Human Rights Watch’s 2011 report and this one, Turkey has both ratified and withdrawn from the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combatting Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, the gold standard for tackling gender-based violence in Council of Europe member states. Turkey was in fact the first country to ratify the convention, which opened for signature on May 11, 2011, in Istanbul. On March 20, 2021, Turkey also became the first country to withdraw from it, rejecting the convention’s inclusive approach to sexual orientation and gender identity as evidence that the convention had been “hijacked by a group of people attempting to normalize homosexuality – which is incompatible with Turkey’s social and family values,” in the words of the president’s communications chief. Many lawyers and activists working on women’s rights and LGBT rights say that withdrawal from the convention was a major setback, demonstrating lack of political commitment to gender equality, without which there remain huge obstacles to combatting domestic violence in Turkey and addressing its root causes.

While recommending that Turkey rejoin the Istanbul Convention, this report notes that key provisions of the convention are enshrined in Turkey’s Law to Protect the Family and Prevent Violence against Women (Law No. 6284). Moreover, Turkey is bound by other international human rights law obliging it to combat violence against women. Notable among these are the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Turkey is obliged to implement European Court of Human Rights judgments, including those relating to the Court’s finding of a pattern of state failure to protect women from domestic violence in the case of Opuz v. Turkey, and 4 other similar cases.

In January 2020 the Interior Ministry restructured police units that handle cases falling under Law No. 6284 and the Justice Ministry set up dedicated courts to hear such cases. It was therefore especially important to hear the police and judges’ view of the challenges of the work in these new frameworks. Their assessments are provided in Chapter 3 of the report. More resources for the police units dealing with domestic violence and increased capacity for judges and prosecutors are needed to support their work.

Unfortunately, the Family and Social Services Minister did not grant permission for Human Rights Watch to meet with representatives of the ministry or the Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers, bodies charged since 2012 with a coordinating role around the implementation of protective and preventive orders at the provincial level and providing access to social services for victims of domestic violence. It was therefore not possible to reflect the ministry’s views or those of the centers in this report.

Authorities should address gaps in protection for victims of violence, including by sanctioning perpetrators for breaches of preventive orders, such as with short periods of detention. At the same time, the authorities should ensure that the deterrent purpose of preventive orders is reinforced by timely prosecution of perpetrators of domestic violence. The two tracks of prevention and prosecution are necessarily separate and independent of each other but should be well synchronized to secure an effective outcome for victims. In some of the key cases examined in the report this had not happened.

The Family and Social Services Ministry’s July 1, 2021 action plan on combatting violence against women contains little new data or findings about the impact of the existing framework for combatting domestic violence or about the work of the Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers over nine years, and the plan avoids any mention of perceived gaps in protection and ongoing challenges. Omitted too are the specific findings of international bodies that have monitored Turkey’s efforts to combat violence against women and Turkey’s obligation to implement the European Court of Human Rights’ judgements in the Opuz and related cases.

The March 2022 report of the 2021 parliamentary commission examining the causes of violence against women similarly includes few findings and little analysis about the implementation of Turkey’s extensive framework to combat domestic violence but acknowledges the gaps in protection by offering many recommendations to improve coordination between agencies, to increase awareness, capacity, resources, monitoring and training, and to standardize data collection.

In order to comply with its obligations to protect victims of domestic violence, the Turkish government needs to ensure better implementation of protective and preventive orders; better collection and publication of data through collaborative efforts by the Justice, Interior and Family and Social Services ministries; greater focus on measuring and evaluating the impact of measures to prevent and respond to domestic violence, and reporting of such evaluations back to the public; and better collaboration with civil society organizations specializing in women’s rights and combatting violence against women.

Methodology

This report is based on research by Human Rights Watch researchers who conducted in-person interviews in Ankara, Diyarbakır, and Istanbul as well as phone interviews with persons or non-governmental organizations based in Aksaray, Antalya, Gaziantep, Eskişehir, İzmir, Kırıkkale, Adana, Batman, and Nevşehir throughout 2021.

Researchers undertook a thorough detailed analysis of case histories, availing of access to women’s complaints, court decisions, records of trial hearings, and detailed interviews with some survivors of domestic violence, lawyers representing victims or their families, and representatives of non-governmental organizations that work on protecting women’s rights and combatting violence against women.

Human Rights Watch interviewed ten women who were survivors of violence, the mother of a woman killed by her husband, and fifteen lawyers who represented the women whose cases are discussed, and analyzed 18 domestic violence case files where the authorities had taken steps to protect the victim.

The researchers interviewed seven judges and a retired judge, six of whom were with Istanbul Family Courts, two prosecutors, and police officers in the unit to deal with cases of domestic violence and violence against women in nine İstanbul districts. Human Rights Watch’s request to the Directorate General of Women’s Status of the Ministry for Family and Social Services for permission to visit the Istanbul provincial Violence Prevention and Monitoring Center was denied. Further requests to the Family and Social Services Ministry, including to the minister’s office, to visit the center received no response.

On April 20, 2022, Human Rights Watch wrote to the ministers of interior, justice, and family and social services, regarding six cases of women killed by spouses. A request was made of each ministry for up-to-date information on whether following the women’s deaths the relevant authorities had conducted investigations into the possible failure of state authorities to exercise due diligence in enforcing effective protective measures in response to the women’s complaints of ongoing violence and harassment, and the outcome of any such investigations. On May 12, Human Rights Watch received a response from the interior ministry containing information supplied by the General Security Directorate. The information supplied is included with the case histories in Chapter 2 of this report. The other ministries did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s letter by the date of publication of this report.

The researchers interviewed lawyers and activists with twelve nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and women’s rights centers of bar associations in addition to six lawyers and a journalist specializing in domestic violence cases. Some of the cases in the report were identified to Human Rights Watch by lawyers and NGOs, while others were identified by Human Rights Watch via media reports or social media platforms.

The female researchers interviewed all individuals in Turkish in person and via WhatsApp calls. No interviewee received compensation for providing information. Pseudonyms have been used for four and initials for two women who requested their names be withheld for privacy and security reasons. These pseudonyms were chosen randomly, and do not reflect their background or ethnicity.

This report focuses on women and girls as victims and survivors of domestic violence. While men and boys are also victims and survivors of domestic violence, women and girls are overwhelmingly disproportionate victims of this form of abuse in Turkey and globally.

I. Background and Legal Framework

Around four out of ten women in Turkey say they have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by husbands or partners at some time in the course of their lives, according to the July 2021 Turkish government action plan on domestic violence, citing the most recent available government data from 2008 and 2014.[1]Women’s rights groups and independent media have regularly recorded hundreds of femicides in Turkey annually.[2] Turkey’s Ministry of Interior provides fluctuating numbers of femicides over the past five years. The lowest was 268 femicides in 2020 and the figure for 2021 was 307 femicides.[3] All these are judged by the Interior Ministry to be murders of women falling within the scope of Turkey’s Law to Protect the Family and Prevent Violence against Women (law 6284), and thus mainly linked to domestic violence.

With respect to the number of incidents of domestic violence recorded by the police and gendarmerie over the past six years, the published figures record a steady rise. In 2016 there were 162,110 recorded incidents and this had risen to 268,817 incidents in 2021.[4]

Demonstrations drawing large numbers of women together with campaigning by the many women’s rights groups in Turkey have raised public awareness of the issues.[5] This has undoubtedly prompted the government in turn to attempt to demonstrate its commitment to combatting violence against women. In April 2022, a new bill before parliament brought in several measures aimed at increasing penalties for perpetrators of domestic violence and introducing the crime of stalking into the Turkish Penal Code. Stalking will be punishable with a six month to two-year prison sentence. In cases where a perpetrator who engages in stalking is subject to a preventive order barring them from contacting the victim, the penalty increases to between one and three years in prison. The law also punishes the intentional killing of a woman with a prison sentence of aggravated life imprisonment. The law also makes intentional injury of women a “catalogue” offense enabling perpetrators to be placed in pretrial detention; slightly increases penalties for crimes such as murder, intentional injury, torture, torment and threats when perpetrated against women, and requires courts to provide a fully reasoned explanation if granting perpetrators discretionary reductions to sentences for good conduct.[6]

The Interior Ministry in April 2022 also issued a new circular setting out a raft of measures to combat domestic violence. They include establishing local risk management teams to monitor threats to victims of recurrent domestic violence and those at high risk, creating a system of instant notification to the police when convicted perpetrators of domestic violence are released from prison, increasing the use of electronic tags to be worn by perpetrators, providing more training for police, and increasing resources.[7]

Withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention

Notwithstanding subsequent government moves of this kind to demonstrate a commitment to tackling domestic violence, Turkey’s 2021 withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention triggered alarm among domestic women’s rights groups and internationally. They see it as indicative of a lack of commitment by Turkish authorities to protecting women from violence and to promoting gender equality.[8] The main opposition parties in Turkey’s parliament have consistently and strongly condemned the withdrawal, lodged appeals against it and been vocal in criticizing Turkey’s track record in combatting domestic violence.[9] In November 2021, Turkey’s highest administrative court rejected appeals against the withdrawal, although a final decision of the court on whether the withdrawal had been conducted in an unlawful manner was outstanding at the time of writing.[10]

Turkish government statements on the convention have narrowly focused on registering concern that it adopts an inclusive approach to protection. The convention provisions apply to victims “without discrimination on any ground” including sexual orientation and gender identity. Government statements have indicated that the convention’s obligation to also protect lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people justified its withdrawal as a state party. The most unambiguous statement is from March 21, 2021, when the president’s communications chief defended the decision saying that the convention had been “hijacked by a group of people attempting to normalize homosexuality – which is incompatible with Turkey’s social and family values.”[11]

The Turkish government is responding to, and promoting, a familiar set of misrepresentations about the Istanbul Convention that have been exploited for political purposes in Turkey, and by right-wing governments elsewhere. In 2021, Poland’s parliament set in motion a bill calling for withdrawal from the convention,[12] and, in 2020, Hungary declined to ratify it.[13] The convention has become a target of the anti-gender movement and governments that use the rhetoric of ‘traditional values’ as a wedge issue to push back against LGBT and women’s rights and to reject the convention as a foreign imposition. In the claims of those opposing the Istanbul Convention is a plethora of misinformation including that the convention imposes same-sex marriage, prescriptive sexuality education, excludes men, erases distinctions based on gender, threatens the family, introduces a third gender category, and interferes with migration policies. To counter this, the Council of Europe has published a fact sheet dismantling these myths.[14] In rejecting the convention these governments like to assert they can combat violence against women while ignoring binding international human rights law.

Despite withdrawing from the convention, Turkey still has its Law on the Protection of the Family and to Combat Violence against Women (Law No. 6284) which derives many of its provisions from the convention.[15] Some of the key provisions are those related to issuing protective and preventive orders. Law No. 6284 also established a system of coordination between different government agencies and social services combatting violence, notably through establishing Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers in each province, and enables the provision of temporary financial support and alimony to beneficiaries of protective orders.

Police, prosecutors, and judges to whom Human Rights Watch spoke, all emphasized that Law No. 6284 contains all the legal measures they believe they need to respond to domestic violence allegations robustly, allowing them to target perpetrators and protect victims. They said that they rely entirely on the provisions outlined in this law to do their work. In a political context in which civil servants and members of the judiciary are regrettably not encouraged to offer opinions based on their own professional experience, Human Rights Watch did not attempt to solicit their views on the possible impact of withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention on the wider effort to combat violence against women.[16]

The Minister for Family and Social Services has rejected the idea that withdrawal from the convention has implications for combatting domestic violence, commenting to a parliamentary commission examining the causes of violence against women that “it is a huge injustice to say that combatting violence against women or the gains of women rights have been thrown in the bin with Turkey leaving the Istanbul Convention. We withdrew from the Istanbul Convention, but what’s changed in women’s rights and combatting violence? Nothing has changed.”[17]

Women’s rights lawyers on the other hand told Human Rights Watch that the withdrawal from the convention is a major setback, demonstrating lack of political commitment to gender equality, without which there exist huge obstacles to combatting domestic violence and addressing its root causes. One lawyer at the Istanbul Bar Association Women’s Rights Center expressed the view that, without the Istanbul Convention, Turkey’s Law No. 6284 is “like a building whose foundations have been removed.”[18]

In withdrawing from the convention, Turkey is no longer subject to the scrutiny of the Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women (GREVIO), the committee charged with monitoring states’ fulfillment of their obligations under the convention. Several women’s rights lawyers and the founder of a women’s rights organization focused on domestic violence voiced the view that the Presidency’s motivation for withdrawing from the convention might also be to escape the scrutiny of GREVIO monitoring.[19] The GREVIO in 2018 issued an important baseline report assessing the state of Turkey’s adherence to the convention and offering detailed recommendations. Regarding the implementation of protection orders, GREVIO focused on the state’s obligation to protect women and the importance of accountability for failure to protect, urging the authorities to:

36.b. exercise due diligence to (1) systematically review and take into account the risk of revictimization by applying effective measures to protect victims from any further violence and harm, and (2) investigate and punish acts of violence;

c. hold to account state actors who, in failing to fulfil their duties, engage in any act of violence, tolerate or downplay violence, or blame victims; [20]

GREVIO also advised that in analyzing cases of femicides, to prevent such future killings, the Turkish government should also “[hold] accountable both the perpetrators and the multiple agencies that come into contact with the parties.”[21]

In making these recommendations, GREVIO relied in particular on the findings of the European Court of Human Rights in its judgment in Opuz v. Turkey, a case concerning the failure of Turkish authorities to protect a mother and daughter from recurring and escalating violence by the daughter’s husband, culminating in the mother’s murder. The Court found that despite receiving repeated complaints and having knowledge of the real and imminent risks the women faced, the authorities had failed to protect them and failed to ensure that perpetrator was held accountable. The Court found violations of article 2 (right to life) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), article 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment) and article 14 (prohibition of discrimination).[22] Since then the Court has made similar findings in at least four other similar domestic violence cases against Turkey and the Committee of Ministers has linked the cases together for the purposes of monitoring implementation.[23]

All Council of Europe member states have an obligation under the ECHR to implement individual and general measures ordered by the European Court in its judgments. The Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers supervises states’ obligation to execute judgments, periodically reviewing the state of execution and issuing decisions and resolutions urging measures the state should take to address the shortcomings that led to the finding of violations and thereby introducing concrete reforms or other measures to prevent a recurrence of those violations.

Despite withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention, Turkey is still bound by other international instruments requiring resolute measures to combat domestic violence, notably the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the UN Convention against Torture.

The CEDAW Committee, responsible for monitoring states’ adherence to and implementation of CEDAW, has leveled robust criticism at the Turkish authorities for failure to implement applicable legislation concerning protection orders and injunctions. In its 2016 concluding observations on Turkey’s seventh periodic report under CEDAW, the committee focused on the authorities’ failure to protect women who had obtained protection orders, observing that: “…protection orders are rarely implemented and are insufficiently monitored, with such failure often resulting in prolonged gender-based violence against women or the killing of the women concerned.”[24] The committee went on to recommend that the Turkish authorities: “[v]igorously monitor protection orders and sanction their violation, and investigate and hold law enforcement officials and judiciary personnel accountable for failure to register complaints and issue and enforce protection orders.”[25]

As the cases included in Chapter 2 of this report show, the Turkish government still has a long way to go to implement this final recommendation. In this respect, a judgment of Turkey’s Constitutional Court published in December 2021, discussed in Chapter 3, breaks new ground. The judgment finds a catalogue of state failure amounting to violation of a woman’s right to life in substantive and procedural terms. The court determined that public officials, prosecutors, and judges had failed to take the necessary steps to protect a woman who had lodged multiple complaints with the authorities before she was killed by her former husband.[26]

Turkey’s Latest Action Plan to Combat Violence against Women

On July 1, 2021, the day that Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention became final, President Erdogan announced a new Ministry of Family and Social Services five-year action plan on combatting violence against women.[27] As noted by the prominent women’s right group Mor Çatı (Purple Roof), which runs a shelter, the 216-page action plan is significant for making no mention of the Istanbul Convention, the GREVIO baseline report on Turkey from 2018, or the CEDAW Committee’s specific recommendations to Turkey in 2016.[28] It also makes no mention of Turkey’s obligations to implement the Opuz and related judgements. Where international legal obligations and guidelines from intergovernmental bodies like the CEDAW Committee are cited at all, they are cited in purely general terms ignoring the mass of analysis and recommendations made over the past few years on the situation in Turkey. This is a disappointing approach for an action plan aimed at combatting Turkey’s widespread and entrenched problem of violence against women. Mor Çatı has noted, too, that omitting the term “gender equality” from the plan is indicative of the government’s ideological stance against promoting equality between men and women.[29]

The 2021-2025 action plan to combat violence against women is the fourth of such plans, and yet not only is there no discussion of the outcome of previous five-year plans, but the data and evidence base informing the plan is weak and outdated. The plan relies on the most recently conducted research findings from the ministry’s reports on “Research on Domestic Violence Against Women in Turkey” conducted in 2008 and 2014 to analyze categories and frequency of violence, and demographics.[30] The other statistics that form the basis of the plan include judicial statistics about numbers of court cases concerning complaints about domestic violence which are not sufficiently disaggregated to be informative and numbers of murders of women provided by the Interior Ministry. No data has been provided by the Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers operating in every province under the Ministry of Family and Social Services despite their coordinating role in combatting domestic violence.

Of relevance to this report are two of the action plan’s goals: “capacity enhancement to improve protective and preventive measures” and “collecting data and statistics.” Regarding protective and preventive orders, the plan lays out strategies such as “ensuring the risk factors of the cases are determined in advance and that the case is intervened in an effective and timely manner.”

The plan proposes a raft of measures including: visits by family social support personnel (aile sosyal destek personeli) to improve risk assessments; the involvement of social services, women’s sections at the municipalities, and schools and health institutions in reporting violence to relevant authorities; support for victims of violence from social services; steps to promote socioeconomic empowerment of victims; increased effectiveness of law enforcement practices; better communication; increased capacity of health services for victims; and the maintenance of services during emergencies (such as the covid pandemic).

These proposals are spelled out in more detail than in previous action plans. However, to be meaningful, the government needs to monitor and measure their implementation and effectiveness and report back transparently to the public, making statistics and findings fully available.

The goal relating to the collection of data and statistics is much needed but its success will depend on the willingness of the government to allow systematic collection of data and in a fully disaggregated form. The data should be presented transparently to the public so as to record the extent to which the authorities’ own measures and court decisions succeed or fail to protect victims of violence and prevent its recurrence.

The plan also includes the positive recommendations that “stalking” and “forced marriage” should be separately named as crimes in the Turkish Criminal Code, which could provide additional protections from domestic violence. A new law passed by parliament on May 12, 2022, for the first time introduces the crime of stalking, with a prison sentence of six months to two years. The offense of “disturbing a person’s calm and tranquility” (article 123 of the Turkish Penal Code) which has been used to prosecute stalking cases, had been criticized by women’s rights lawyers as ill-matched to the pattern of persistent harassment and intimidation by multiple means which stalking cases often entail.[31]

In March 2022, a parliamentary commission set up in 2021 to examine the causes of violence against women, issued a lengthy report. Similar to the government’s action plan, the report includes few findings and little analysis about the implementation of Turkey’s extensive framework to combat domestic violence but, as testament to the persistent problem, an 86-page recommendations section which acknowledges the acute gaps in protection. The recommendations are focused on improving coordination between agencies, improving monitoring of measures to combat domestic violence, increasing capacity, resources and training of police, judges and all other public authorities, creating new mechanisms and outreach to women at risk, and standardizing data collection to combat violence against women.[32] Throughout the parliamentary commission report, there is much emphasis placed on the rising number of protective and preventive orders issued by courts and police year on year without scrutiny of whether this in practice has meant women are today better protected against domestic violence.

What are Protective and Preventive Orders?

Protective and preventive orders are included in Turkey’s Law No. 6284.

The police, the district governor’s office and the courts have the power to issue protective orders (articles 3 and 4 of Law No. 6284) which can include a range of measures designed to ensure the victim’s safety and are not focused on the perpetrator. Women typically apply first to the police, who can offer the victim and any children a place in a shelter or protection on call. Victims can also secure temporary financial support when issued a protective order by police. Courts mainly assess complaints by victims referred to them by the police, approve or reject measures taken by the police, and issue further protective measures such as ordering a change in the individual’s workplace and in life-threatening situations, or ordering that information about the individual’s identity and whereabouts in official records be concealed to protect them from being found and contacted by their abuser. In exceptional cases, the court can offer the victim a new identity.

The much more widely used preventive order (article 5 of Law No. 6284), issued by a court, is directed at the perpetrator and may include a variety of different measures in force for a period of time ranging from a week to six months. At the minimum this includes an order to cease all abusive, violent and threatening behavior. It may also include a restraining measure ordering, for example, the perpetrator to stay away from the victim and her home, workplace, and relatives, and not to attempt to communicate with the victim or her relatives. The police can issue a preventive order imposing these measures immediately if they assess an imminent risk to the victim. The order is then submitted to a family court for review on the next working day and the court has 24 hours in which to conduct its review. Additionally, courts may order the perpetrator to refrain from alcohol or drugs in the presence of the victim, to submit to medical treatment, or to hand over a licensed firearm in their possession. The court can impose restrictions on the terms of the perpetrator’s contact with children or revoke it and can also award temporary alimony to victims. Such orders are available when a suspected perpetrator is accused of all forms of verbal harassment, threats, physical violence, and stalking.

If perpetrators breach the terms of the order, they can face sanctions including short periods of detention. In some cases, they may be fitted with an electronic tag to alert the authorities if they approach the victim.

Suspected perpetrators may also be subject to criminal investigation and prosecution in a separate but parallel process. However, as our analysis shows, the investigative and protection processes may lag behind and seem to function without sufficient consideration of the trajectory of protective and preventive orders issued by courts.

In late 2019 and January 2020 steps to reorganize the police, prosecutorial and judicial response to combatting domestic violence were introduced and implemented.

The Ministry of Justice issued a December 2019 circular outlining steps to “overcome problems during the implementation of preventive and protective orders.” These included:

- introducing specialist prosecutors to deal with domestic violence and violence against women,

- detailed guidance on applying protective orders and dealing with the police,

- detailed guidance on referral to social services and the Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers,

- guidance on use of police risk assessment forms and social services’ social research reports to conduct needs assessments for protective orders, and

- measures to protect identity and whereabouts in high-risk cases.[33]

The Council of Judges and Prosecutors, the body with oversight of the administration of the judiciary and prosecutorial authorities, followed this with a decision assigning some family courts in each province to deal exclusively with protective and preventive orders.[34] With effect from January 1, 2020, judges assigned to these courts no longer rule on other areas covered by the other family courts such as divorces and child custody arrangements. This is an important measure aimed at speeding up the issuing of preventive and protective orders.

Turkey’s General Directorate of Security introduced its own measures in January 2020 to rearrange and increase the number of police units assigned to dealing with domestic violence, including issuing preventive and protective orders.[35] Many women officers have been appointed to work in the units and in each of the nine units Human Rights Watch chose to visit, from January 2020, a woman superintendent had been appointed to run the unit.

While judges deal mainly with case files, police officers deal with victims and perpetrators and play the frontline role in efforts to combat domestic violence. Domestic violence police units are composed of officers who undertake different functions, including conducting interviews with victims and perpetrators, preparing reports to the courts and prosecutor’s office and since January 2021 completing a 12-page risk assessment, serving perpetrators with protective or preventive orders, monitoring the orders, and following up with victims.

The Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers (Şiddet Önleme ve İzleme Merkezleri, abbreviated to ŞÖNİM) in each province are another central pillar of the effort to combat domestic violence. Organized under the Ministry of Family and Social Services, the centers are responsible for tracking the implementation of protective and preventive orders, coordinating between the courts, the police, and social services, and for placing victims in shelters, assessing risk, and following up on steps to ensure their protection. The centers provide a one-stop shop aimed at providing victims of domestic violence with coordinated assistance from social services, the health system, and the justice system.[36]

II. Domestic Violence and the Use of Protective and Preventive Orders: Cases

Human Rights Watch analyzed 18 cases of domestic violence, involving a variety of abusive behavior from threats and stalking to physical violence and murder, in which victims had applied for state protection. One case dates from 2022, ten date from 2021, two from 2020, four from 2019, and one from 2017. The cases are organized under different thematic headings and include the facts Human Rights Watch was able to assemble from official documentation, court records and information supplied by lawyers, and where possible from the women survivors of violence themselves or their family members.

The cases demonstrate the uneven success of applying preventive orders under article 5 of Law No. 6284 issued by courts against perpetrators (see appendix for details of the relevant provisions covered in the article), including variations in the specified duration of the measures, apparent lack of monitoring of orders’ effectiveness, and inconsistency in imposing or absence of sanctions for breaches of preventive orders. In some cases, women also secured protective orders though, as the statistics discussed in Chapter 3 show, preventive orders are far more widely issued than protective orders in which women opt to move to a shelter or receive an order entitling them to police protection when they call for it. In the case of one woman who is a refugee, the police and court promptly issued a preventive order in response to her complaint of being threatened by her former husband but failed to notify her for ten days, leaving her unaware of the outcome of her complaint. In most cases reviewed, the history of violence had culminated in separation or divorce and preventive orders were employed against former spouses and partners. In several of the cases, after the facts are discussed, recommendations are made about conducting investigations into what went wrong and who should be held responsible.

One of the striking elements in many of the cases is that victims, their family members or their lawyers, felt compelled to turn to social media to demand assistance from the authorities or to object to the release of perpetrators. Police and judges Human Rights Watch interviewed confirmed that social media has become a successful means of highlighting cases and triggering a response from authorities where traditional complaint methods have failed. Their views are considered in detail in Chapter 3. It is concerning to see that such direct public appeals from women or their lawyers have become a means of compensating for the authorities’ shortfalls in resolute implementation of preventive and protective measures.

The cases below also include details of steps to investigate and prosecute perpetrators for domestic violence. Prosecutors typically pursue charges for threats, insults, disturbing the peace, or intentional injury, but these are all offenses for which the sanction is typically a fine or suspended sentence, or for which courts issue a decision “not to pronounce the verdict” on condition the defendant does not re-offend within five years – a form of suspended sentence. Such penalties may not act as a deterrent, with the perpetrator effectively escaping punishment for domestic violence. Prosecutions also tend to take place a long time after the commission of the offense, and while the trial is ongoing the perpetrator may already have repeatedly reoffended.

Victims Killed Despite Having Been Granted Preventive and Protective Orders

Yemen Akoda

Yemen Akoda, age 38, was the mother of three children and worked at a factory as a tea maker. On June 24, 2021, her husband Eşref Akoda shot her dead outside her home in the central Anatolian town of Aksaray. Prior to her killing courts had on four occasions issued preventive orders to keep Eşref away from Yemen.[37]

Yemen first received a preventive order in February 2021 after her husband threatened and harassed her to prevent her pursuing a divorce. In a divorce protocol signed in the presence of a lawyer, Eşref had agreed to leave the family home but he later changed his mind and allegedly told his wife he did not want to get divorced. When Yemen insisted on pursuing the divorce, Eşref went to a police station and complained to the police, alleging that his wife had kicked him out of the house. Police officers invited Yemen to come to the station and provide a statement. Yemen obtained the first 30-day preventive order, restricting Eşref from going to the house or to her workplace. When the preventive order expired, Eşref began to harass Yemen at her house and workplace, on one occasion threatening to kill himself if Yemen proceeded with the divorce. In total, Yemen obtained four preventive orders between February and June 2021, all of which were, according to Yemen’s lawyer, for short periods of time, ranging from a week to a month.

Eşref violated two of them by harassing Yemen at her home or workplace while they were in force. Yemen’s lawyer filed complaints in regard to these violations at the Aksaray prosecutor’s office. The Aksaray courts did not impose any sanctions on Eşref for violating preventive orders. The Aksaray prosecutor ruled not to prosecute him for his harassment, citing lack of evidence.

On June 24, 2021, after shooting Yemen dead outside her home, Eşref fled the scene and was allegedly himself shot by police officers and died of his injuries. The house is close to a police station and officers had been immediately dispatched to the scene in response to the gunshots. Two of the Akoda children were subsequently placed in state care.

Yemen’s older daughter wrote on her Twitter account after her mother’s death in a tweet subsequently deleted: “My mother asked the prosecutor for protection. « I can’t give you protection unless he hurts you, » he said. There, he hurt her, now protect my mother.”[38]

On the day of the shootings the prosecutor’s office issued a statement announcing a media blackout on the case and a restriction order on the investigation file, limiting access to the evidence in the file on the grounds that its disclosure could jeopardize the investigation. The statement said the media blackout was necessary to ensure the investigation was completed properly and to protect the couple’s children but also on grounds of “preventing similar incidents” and “the risk of disturbing the public order, the possibility of further irreparable damage and the importance of the issue.”[39] On June 25, 2021, the prosecutor’s office released another statement announcing a criminal and administrative investigation into parties or persons responsible for failure to implement the preventive orders which had been served on Eşref Akoda.[40]

No report or update had been issued regarding the outcome of these investigations at the time of writing. Human Rights Watch wrote to the interior, justice, and family and social services ministries requesting information about the outcome of the administrative and criminal investigations. The interior ministry on May 12, 2022, informed Human Rights Watch that the General Security Directorate had provided the information that there was an ongoing (administrative) investigation into two members of staff. The other ministries did not respond.[41]

Recommendations:

- The authorities should conduct a full and transparent investigation to assess whether, on the basis of all the available information about the risk Eşref posed to Yemen Akoda, authorities could have taken further action to prevent her killing.

- In particular, the investigation should examine whether the authorities made every effort and exercised due diligence in assessing the risk Eşref posed to Yemen, whether the preventive orders courts issued were of sufficient length and adequate to addressing the risk, and why both the courts and the prosecutor’s office decided not to sanction Eşref for twice violating the terms of the preventive orders. The prosecutor’s concern with preventing media coverage of the incident should not become a pretext for the authorities to conceal the full results of an inquiry into whether authorities used all available measures to protect Yemen from her husband and prevent her from being subject to further violence and, ultimately, murder.

Remziye Yoldaş

Veysi Yoldaş, 31, shot dead his wife Remziye Yoldaş, 28, in the center of Diyarbakır on August 28, 2020, in the presence of their 7-year-old daughter and other witnesses. At the time of her death, Remziye had received a 30-day preventive order (under Law No. 6284 article 5/1/a,c,d), forbidding her husband from threatening, insulting, and humiliating her. The order also barred him from contacting her or approaching her residence or workplace and her relatives and children.[42]

Prior to killing Remziye Yoldaş, Veysi Yoldaş had on August 9, 2020, absconded from a semi-open prison to which he had been transferred in 2020 to serve the remainder of a prison sentence after being convicted on theft and drugs-related charges.[43] Remziye’s lawyer told Human Rights Watch that Veysi had called Remziye after absconding from prison and began to threaten her when she refused to join him to start a new life elsewhere evading the authorities. Remziye applied to the police to complain that she felt at great risk. According to Remziye’s lawyer and her sister’s and father’s statements to the court handling her murder case, she had told the local police that Veysi had absconded from prison and feared he would kill her, but she was not taken seriously.

Remziye Yoldaş’s father Ahmet Tura, 61, later testified before the Diyarbakır prosecutor and in court that Veysi Yoldaş, who was living as a fugitive, had come to his shop days before the murder on August 28 and had tried to take away Remziye. He said that Remziye had resisted, that Veysi had put his hands round her neck and choked her, threatening her with the words, “If you don’t come with me, I’ll kill you and your whole family.”[44] Tura told the court that after Veysi Yoldaş released Remziye and left the shop without her, Remziye, on the same day, had gone to a nearby police station and filed another complaint. The police had issued a preventive order, approved on August 24 by a court for a period of 30 days, banning Veysi Yoldaş from contacting her. On the same day, Remziye had also filed a petition for divorce to a family court, citing Veysi’s threats to her and her family and claiming that they had no security of life. He shot her dead just four days later.

Police apprehended Veysi Yoldaş on September 6, 2020, and he was prosecuted on charges of “intentional and premeditated murder of a spouse.” On February 8, 2022, the Diyarbakır 7th Assize Court convicted him of intentional killing and sentenced him to aggravated life imprisonment as well as an additional sentence of six months for “intentional endangerment of general safety” and one year and a fine for “possession of an unlicensed gun.” Remziye’s lawyers have appealed the verdict seeking conviction on charges of premediated killing as well. The case is at appeal.

Recommendation:

The investigation into the murder of Remziye Yoldaş, should establish why the authorities did not identify the severity of the risk to Remziye’s life, despite her complaint to the police when Veysi Yoldaş absconded from prison and issued threats to her in a phone call, later physically assaulting her; and whether there was any monitoring to see if the 30-day order was being observed or any steps taken to ensure the order would be effective.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the interior, justice and family and social services ministries requesting information about the outcome of any investigations into the authorities for failing to identify the severity of the risk to Remziye Yoldaş. The interior ministry on May 12, 2022 informed Human Rights Watch that the General Security Directorate had provided the information that an (administrative) investigation had been opened against ten members of staff (three of them senior officers) and that nine had received various disciplinary sanctions. No detail was provided about the sanctions. The other ministries did not respond.[45]

Ayşe Tuba Arslan

Ayşe Tuba Arslan, 45, worked in a kindergarten. Her ex-husband Yalçın Özalpay attacked her with a meat cleaver and a knife in Eskişehir on October 11, 2019. She died of her injuries on November 24, 2019. The attack followed a long history of domestic violence which had already led to the couple’s separation in September 2018 and divorce in March 2019 after a 25-year marriage.[46]

The Eskişehir chief prosecutor’s office confirmed after her death that between September 2018 and October 2019, Ayşe Tuba Arslan had made 23 complaints to the police and prosecutor’s office regarding insults, threats and injuries caused by Yalçın Özalpay.[47] The Eskişehir prosecutor’s office declined to prosecute in ten of her complaints, citing lack of evidence. In eleven cases prosecution was initiated and in three of these prosecutions, one of which consisted of two merged files, Özalpay was acquitted for lack of evidence. On November 3, 2018, Özalpay allegedly threatened to “shoot and kill Arslan,” for which he was prosecuted for making “insults and threats” but received a form of suspended sentence whereby the court does not pronounce a verdict (hükmün açıklanmasının geri bırakılması) on condition that the offender does not repeat the offence over a five-year period. In two other cases, he received fines, in one case the court declined to impose a penalty, and in three cases the prosecution was ongoing at the time of Arslan’s murder.

Arslan received four preventive orders from Eskişehir courts (under Law No. 6284 articles 5/1/a,b,c,d) for periods of time ranging from a month to six months. Yalçın Özalpay violated these injunctions multiple times, and Arslan notified the authorities of these violations in eight complaints. However, courts did not impose sanctions such as detention on Özalpay for violating the preventive orders, citing lack of evidence, even though Özalpay himself admitted the violations in court hearings.

In five of Arslan’s 23 criminal complaints, the Eskişehir chief prosecutor’s office referred her to the settlement office, established in December 2016 to reduce the workload of the judiciary by offering parties the option not to proceed with a criminal complaint. Arslan refused such settlements.

An Eskişehir Assize Court sentenced Yalçın Özalpay in July 2020 to aggravated life imprisonment for “premediated brutal intentional killing through torment,” (Turkish Penal Code Article 82/1/b) but on June 25, 2021, the Ankara Regional Appeals Court revoked the sentence on the basis that Arslan’s text messages to another man should be considered as “unjust provocation” and ruled that Özalpay sentence be reduced to 24 years.[48] Lawyers engaged in the campaign around the case have lodged an appeal at the Court of Cassation.

Lawyers for Arslan’s parents have pursued a case in the administrative courts against the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Family and Social Services for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages for failure to protect Arslan and being partially liable for her death. On November 24, 2021, the Eskişehir 2ndAdministrative Court rejected the case, accepting the argument of the two ministries that there had been no preventive order in place at the time of Arslan’s murder, and therefore they had not failed to implement any measures. The Arslan family lawyers have appealed this decision. They are also pursuing a case against the Ministry of Justice.[49] A criminal investigation started ex officio by the office of the Eskisehir chief prosecutor into possible negligence by the police, courts, and prosecutors ended in a decision not to prosecute.[50]

Human Rights Watch wrote to the interior, justice and family and social services ministries requesting information on what steps had been taken to investigate whether the authorities had adequately discharged their duty to protect Ayşe Tuba Arslan. The interior ministry on May 12, 2022, informed Human Rights Watch that the General Security Directorate had provided the information that an (administrative) investigation opened against members of staff had ended with a decision to discontinue the investigation (“soruşturma neticesinde işlemden kaldırma karar verildiği”). No explanation for this decision was provided. The other ministries did not respond.[51]

Recommendation: A full inquiry into Arslan’s killing should:

- Assess repeated decisions not to prosecute Özalpay and court decisions to acquit him or to impose fines or a decision of non-pronouncement of verdict;

- Evaluate whether authorities adequately considered Özalpay’s history of abuse in their response to Arslan’s complaints, and whether they took the necessary measures for her protection in light of the pattern of abuse;

- Examine how poor coordination between different authorities may have contributed to Arslan’s murder given the absent or limited involvement from Violence Prevention and Monitoring Center officials who are responsible for a key coordinating role among the judiciary, the police force, and all other agencies;

- Probe the responsibility of the authorities and be capable of holding to account police, prosecutors, and judges, and other public officials for dereliction of duty, negligence or, if appropriate, more serious offenses.

Güllü Yılmaz

Güllü Yılmaz, 30, mother of three children, died of burns in a Diyarbakır hospital on October 29, 2019, 12 days after Can Yılmaz, her spouse of 14 years, poured gasoline over her and their 12-year-old daughter Dilek Yılmaz and set light to them. The daughter survived with minor injuries. Güllü Yılmaz’s death followed two complaints about domestic violence to the police, a preventive order, and a short period in which she stayed in a shelter, the precise timing of which Human Rights Watch has been unable to establish.[52]

According to documents provided by Güllü Yılmaz’s lawyer, she told her husband she wanted a divorce on September 14, 2019, after years of domestic violence. Her husband allegedly responded with threats to kill her children and headbutted her. That day she filed a complaint at an Ergani police station and requested protection. However, later in the day she withdrew her complaint and protection request apparently under pressure from elders in her family. Even so, the authorities initiated a public case against the husband for “causing minor injury,” a case that was concluded two months after Güllü’s death with Can Yılmaz convicted of “deliberate injury of spouse” and sentenced to one year and three months in prison.

On September 29, 2019, Güllü again went to the police station where she reported that her husband had physically attacked her, held a knife to her neck and threatened to kill her. Her lawyers informed Human Rights Watch that she had also obtained a medical report listing a 1-centimeter laceration in her neck and a bruise on the right side of her upper lip from Ergani State Hospital on September 30, 2019. Medical reports involving injuries resulting from attacks require the immediate notification of a police officer present at the hospital at all times. The police detained Can Yılmaz for a few hours on September 29 but released him on the same day.

On October 1, 2019, Güllü was given a 7-day preventive order in line with Law No. 6284 article 5/1/a, b, c, d. The authorities initiated a criminal probe into Can Yılmaz for “deliberate injury of a spouse,” another case which was concluded after Güllü’s death with an Ergani court in December 2019 sentencing Can Yılmaz to an additional four years and three months in prison for armed threats and deliberate injury of a spouse.

Legal documents seen by Human Rights Watch do not indicate whether there was any assessment conducted in Güllü’s case by the Violence Prevention and Monitoring Center.

On October 17, 2019, Can Yılmaz allegedly poured gasoline on Güllü and their daughter Dilek in their house and set light to it. In the court documents of Can Yılmaz’s trial, police officers testified that when she was brought to the hospital, Güllü told them “My husband burnt me!”

On March 30, 2021, Diyarbakır 7th Assize Court sentenced Can Yılmaz to aggravated life imprisonment on charges of “deliberate murder of a spouse with monstrous sentiments” and “attempted murder of a child and a descendant with monstrous sentiments.” Can Yılmaz’s lawyers have appealed the court ruling.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the interior, justice, and family and social services ministries requesting information on what steps had been taken to investigate whether the authorities had adequately discharged their duty to protect Güllü Yılmaz. The interior ministry on May 12, 2022, informed Human Rights Watch that the General Security Directorate had provided the information that “as a result of the necessary inquiry, it had been established that there was no need for an administrative investigation” into police officers (“yapılan incelemeler neticesinde herhangi bir idari soruşturmaya gerek olmadığının tespit edildiği”). No explanation for this decision was provided. The other ministries did not respond.[53]

Recommendation: A full review of the case should:

- Determine why a court issued a preventive order of just seven days after the second recorded violent attack by Can Yılmaz, given the level of risk that he posed to Güllü Yılmaz would have seemed high;

- Confirm whether or not Güllü Yılmaz was offered support while in the shelter and whether or not efforts were made to determine if she was threatened into agreeing to reconcile with her husband;

- Inquire whether her decision to abandon her complaint and request for protection on September 14 should have prompted a fuller risk assessment by the authorities;

- Assess whether the prosecutor should have sought pretrial detention for Can Yılmaz on the second instance of “deliberate injury”, given his alleged violent conduct and death threats.

Pelda Karaduman

Pelda Karaduman was born in February 1999 in Ergani, Diyarbakır. Her cousin, Hüseyin Oruç murdered her in 2017. Authorities failed repeatedly to protect her from abduction, rape, and violent assault when she was a child, culminating in her murder at age 18. She had made eight complaints against Hüseyin Oruç and received two protective orders.[54]

Human Rights Watch interviewed Pelda’s mother Leyla Karaduman and lawyers, reviewed police reports, an indictment, criminal complaints, and medical reports relating to Pelda Karaduman’s case. At the age of 12, in January 2012, Pelda Karaduman was abducted from outside her school in Ergani, a district of Diyarbakır, by her cousin Hüseyin Oruç, who was 20 years old at the time. Mehmet Karaduman, Pelda’s father, filed complaints about her disappearance at the Ergani gendarmerie station and at the district prosecutor’s office immediately afterwards. Pelda remained missing for about 11 months. In late December 2012, Mehmet Karaduman got his daughter back after allegedly assuring Hüseyin Oruç that he would withdraw his complaint if he was allowed to spend a few days with her. According to a medical report, Pelda, then 13, was eight weeks pregnant when she was reunited with her family who were at the time living in the southern province of Osmaniye. The Karaduman family said in their criminal complaint at the prosecutor’s office in Osmaniye on December 31, 2012, that they had moved to Osmaniye to escape societal pressure to kill Pelda to save their “honor” because she had been taken away by a man who had “defiled” her. Pelda and her family said in their complaint that Huseyin Oruç had kidnapped her and raped her repeatedly for a year. Police in Osmaniye proposed a settlement agreement with the perpetrator twice in January 2013 which the Karaduman family refused. Proposing settlements in sexual crimes including rape cases is expressly prohibited under the Turkish criminal procedure code.[55] While in Osmaniye, the Karaduman family contacted the police and the prosecutor at least six times and requested protection at least four times, citing threats from Huseyin Oruç and his family who allegedly called and threatened Mehmet Karaduman. Pelda’s mother Leyla Karaduman told Human Rights Watch that the Oruç family threatened to kill her other two children if Pelda were not returned to them.

The Diyarbakır prosecutor separately investigated and indicted Oruç for kidnapping and sexual abuse of a child (a charge including rape) in 2013. In December 2014, Hüseyin Oruç stood trial in the Diyarbakir 7th Assize Court on charges of “sexual abuse of a child,” “sexual abuse of a child resulting in bodily and mental harm,” and “depriving a person of their liberty.”[56] In December 2014, the court acquitted Oruç of “depriving a person of their liberty,”[57] and ruled that he would face no penalty for rape and sexual abuse.[58] The court justified this in its reasoned decision by incredulously accepting Oruç’s claim that he believed his cousin to be older than 15, and even stating “the victim looked older than 15.” Even if the Court accepted that Oruç believed Pelda was 15, Turkish law provides strict liability for sexual intercourse with someone younger than 15, so that having sex with someone under 15, irrespective of belief or consent is rape under the law.[59]

The Karaduman family told Human Rights Watch that in mid-2013 because Hüseyin Oruç made several death threats against them and their children, they were forced to allow him take Pelda back and decided not to appeal the acquittal. The prosecutor also failed to appeal the case and because Pelda was a child at the time, the lawyer assigned to her could not appeal, as that decision legally belonged to her parents.

After Pelda went back to live with Hüseyin Oruç, she gave birth to two children in state hospitals in Diyarbakır and Osmaniye where one of the children was registered as Leyla Karaduman’s child because Pelda herself was a child at the time. The documentation available to Human Rights Watch does not indicate whether medical authorities had reported the case as a child pregnancy to the police or prosecutor’s office. By law, medical personnel are obligated to report cases that come to their attention which raise issues of child protection or criminal activity to trigger investigations.[60]

On July 23, 2017, at the age of 18, Pelda was found dead at the Diyarbakır home where she lived with Hüseyin Oruç, lying in a pool of blood with a fatal gunshot wound to the heart. Hüseyin Oruç claimed that he and his brother had found Pelda after she had committed suicide. However, on April 30, 2019, Hüseyin Oruç was convicted of killing Pelda. Shockingly, the court reduced Oruç’s sentence because he had alleged Pelda had been unfaithful. The Regional Appeals Court quashed the sentence and on April 19, 2021, ruled Hüseyin Oruç be sentenced to life imprisonment for intentional murder. The case is currently under appeal at the Court of Cassation. The Karaduman family lawyers informed Human Rights Watch that the Karaduman family is receiving threats, and that Pelda’s children remain in the custody of Hüseyin Oruç’s family. The Karaduman family is pursuing a legal case seeking custody of the two children.

Pelda Karaduman’s brutal life and death is attributable at least in part to the repeated and egregious failure over years by the authorities to punish the perpetrator Hüseyin Oruç for abduction and rape of a child, and members of the Oruç family for repeated threats against the Karaduman family and complicity in child abuse, rape, and abduction of Pelda Karaduman. The authorities failed to offer protection to Pelda Karaduman or her family, failed to remove Pelda Karaduman, at the time a child, from the reach of Hüseyin Oruç and his family, and at one stage – in direct contravention of the law – proposed a settlement between the families. Two hospitals apparently failed to report that a child had given birth or to inform the prosecutor, missing another opportunity to investigate the case and prosecute Hüseyin Oruç. There is no mention in the case file of any involvement in the case by the Violence Prevention and Monitoring Center.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the interior, justice, and family and social services ministries requesting information on what steps had been taken to investigate whether the authorities had adequately discharged their duty to protect Pelda Karaduman. The interior ministry on May 12, 2022, informed Human Rights Watch that the General Security Directorate had provided the information that “as a result of the necessary inquiry, it had been established that there was no need for an administrative investigation” into police officers (“yapılan incelemeler neticesinde herhangi bir idari soruşturmaya gerek olmadığının tespit edildiği”). No explanation for this decision was provided. The other ministries did not respond.[61]

Recommendation: There should be a full inquiry into the failings of state authorities (including the police, the prosecutor’s office, the courts, hospital personnel), identifying each duty of care and statutory duty that was breached, assessing the liability of each entity and the individuals that failed Pelda and her family, and setting out measures to be taken to hold all those responsible to account.

Müzeyyen Boylu

Müzeyyen Boylu was a 43-year-old lawyer from Diyarbakır. Her husband, Mesut Issı, killed her on May 19, 2019, after their child’s graduation ceremony. She had obtained three preventive orders from courts in March-April 2018 and in January and April 2019.[62]

According to documents provided by lawyers from Diyarbakır Bar Association’s Women’s Rights Center, which represented Boylu, Boylu filed for divorce from Mesut Issı, her husband since 2012, on February 16, 2018, after years of domestic violence. She was granted custody of their children pending conclusion of the divorce. Boylu filed two criminal complaints with the Diyarbakır Prosecutor’s Office on March 9 and 26, 2018, in which she said Issı had made “threats and insults” against her and had “abducted” her children. Two days later, the Diyarbakır prosecutor ordered a preventive order based on article 5/1/a, b, c, d which banned Mesut Issı from contacting Boylu for 15 days. On January 7, 2019, Müzeyyen Boylu filed another complaint against Issi for “threats and insults.” The next day, the court issued a 30-day preventive order forbidding Mesut Issi from contacting her. On April 16, 2019, Boylu filed a third complaint against Issı citing “threats, insults, and bodily harm.” Two days later she was given a 15-day preventive order again forbidding Mesut Issı from contacting her.

On February 11, 2021, a Diyarbakır court acquitted Issı on charges of threats and insults for an incident dating back to April 14, 2019, due to lack of evidence, but issued a decision that it would not pronounce the sentence of five months imprisonment for “intentional injury” on condition he did not reoffend for five years.

On May 19, 2019, Issı shot Boylu eleven times in front of their two children in Diyarbakır after a school graduation ceremony.

On September 29, 2020, a Diyarbakır court convicted Issı to life in aggravated life imprisonment for “deliberate murder of a spouse.” The Regional Appeals Court approved the sentence, and the case is now at the Court of Cassation.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the interior, justice, and family and social services ministries requesting information on what steps had been taken to investigate whether the authorities had adequately discharged their duty to protect Müzeyyen Boylu. The interior ministry on May 12, 2022, informed Human Rights Watch that the General Security Directorate had provided the information that “as a result of the necessary inquiry, it had been established that there was no need for an administrative investigation” into police officers (“yapılan incelemeler neticesinde herhangi bir idari soruşturmaya gerek olmadığının tespit edildiği”). No explanation for this decision was provided. The other ministries did not respond.[63]

Recommendation: An inquiry should be conducted including to:

- Determine why the length of the preventive orders were both inconsistent and why a preventive order for a shorter period was issued in the face of evidence that his violent behavior was persisting and escalating;

- Assess how the court reached a decision not to pronounce his sentence (a form of suspended sentence) in light of evidence of a pattern of abusive behavior;

- Identify which entities and individuals failed in their duty to protect and recommend appropriate sanctions for those failures.

Repeated Violations of Preventive Orders including Attempted Murder

Nurcan Kaplan

Nurcan Kaplan, 33, and the mother of two children, had lodged repeated complaints that her spouse Tarık Kaplan had committed domestic violence against her during the fifteen years of their marriage and obtained around 12 preventive orders, many of which, she told Human Rights Watch, he had violated. On May 25, 2021, Tarık Kaplan shot Nurcan Kaplan and her mother with a firearm in the centre of Diyarbakir, leaving both seriously injured, as he fled the scene. After public efforts by lawyers to secure effective protection, including by raising the case on social media, Nurcan Kaplan and her mother were offered police protection at their home until Tarık Kaplan was arrested on July 17, 2021, and placed in pretrial detention.[64]

Nurcan told Human Rights Watch that early in her marriage she would take refuge in her parents’ house to escape violence at the hands of Tarık Kaplan. However, she said, her father would beat her and send her back to her husband. Nurcan told Human Rights Watch that whenever she went to police stations to seek help after being beaten by Tarık, the officers would convince her to go back to him despite signs of physical violence.

Since 2013, Tarık Kaplan has been in and out of prison for separate crimes including several relating to violence against Nurcan. Following his release from prison June 2020, Tarık Kaplan violently beat Nurcan. She received protection and was housed in state-run shelters in at least four different cities for about six months beginning in July 2020. Nurcan had to leave her son, who was 13 years old at the time, with her relatives as state-operated shelters do not allow males older than 12 to stay with their parents.[65]

On February 23, 2021, Nurcan and Tarık both attended a hearing at a Diyarbakır court into alleged sexual abuse of their 10-year-old daughter by a third party. The case is unrelated to the history of Tarik’s abusive treatment of Nurcan. The lawyers of Diyarbakır Bar Association’s Women’s Rights Center, who were at the courthouse for separate reasons, said they saw Tarık insult, threaten, and attack Nurcan physically in front of a panel of judges, who had Tarık removed from the court room. A lawyer present reported to Human Rights Watch that the judges, prosecutor, and police officers who saw the incident had not been responsive to the incident and that it had been the lawyers who filed an official complaint against Tarik Kaplan for assaulting Nurcan in the courthouse. Police had briefly detained Tarık Kaplan but released him the same day.