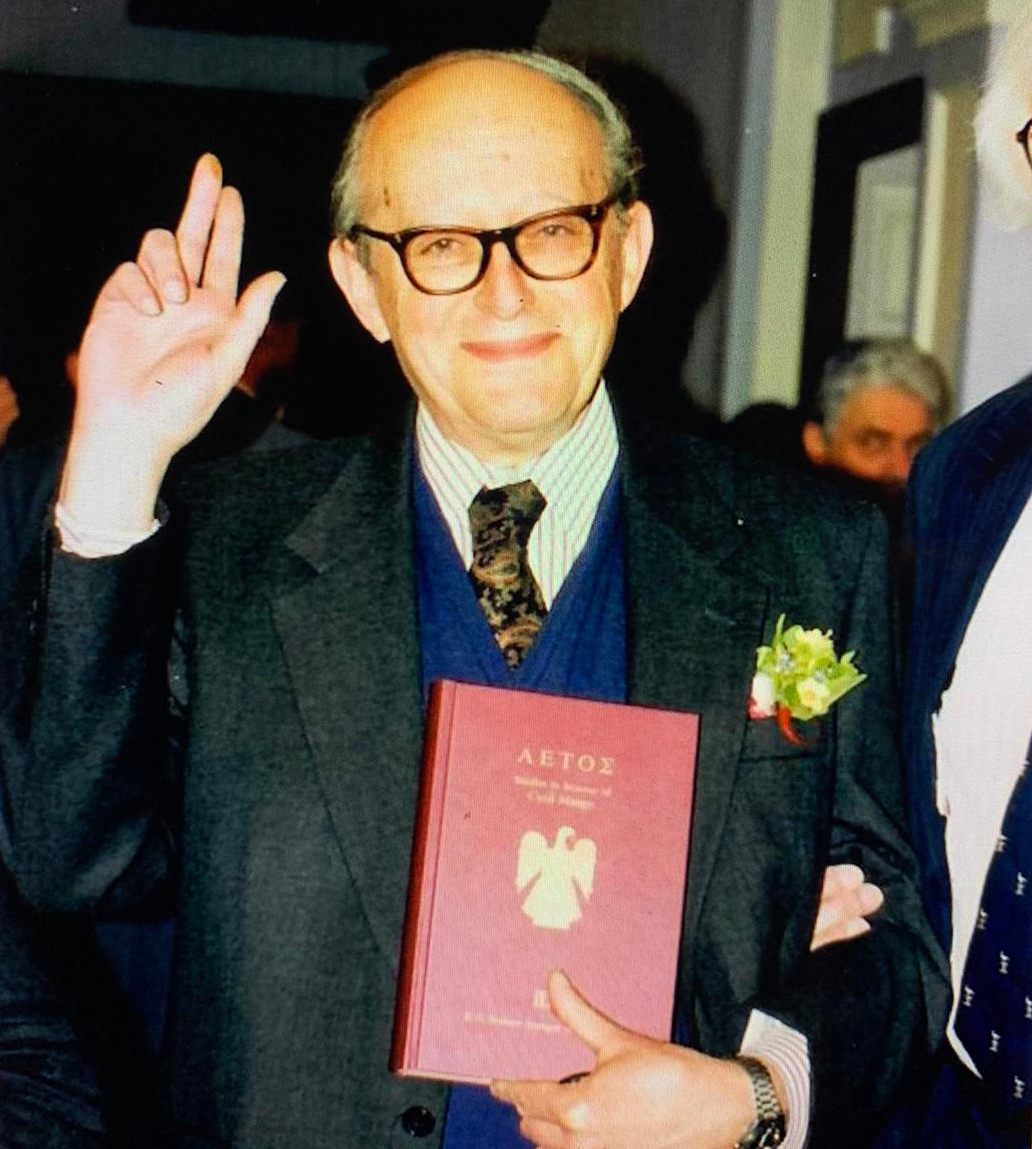

CYRIL MANGO is the byzantologist who took research on Byzantine Constantinople to its highest level. He passed away on the 8 of February 2021.

William Saunders wrote his obituary in the Guardian of March 23, 2021, (photo: Anne McCabe):

« Cyril Mango, who has died aged 92 did much to advance understanding of the history and material culture of the Eastern Roman empire and its medieval successor, the Byzantine empire, centred on the late Roman city of Constantinople.

A native of what in modern-day Turkey became Istanbul, from his youth Cyril developed a great knowledge of the city’s churches and other monuments. They and their counterparts scattered throughout the Byzantine empire remained a major focus of his academic career.

He was not the first to research Constantinople’s art and architecture. The US scholar Thomas Whittemore and his Byzantine Institute had already begun the work of restoring Hagia Sophia, the great 6th-century church, and its mosaics; and the excavations of the Great Palace had commenced before the second world war. But Cyril took the study of Byzantium to an altogether higher level.

In 1940 Robert and Mildred Bliss gave Harvard University a substantial endowment, their mansion at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, and its art collection in order to promote Byzantine and other studies. Cyril joined Dumbarton Oaks in 1951 and remained there until 1963. It gave him the time, opportunity and financial means to pursue his studies.

During these years Cyril joined Paul Underwood, the director of fieldwork at Dumbarton Oaks, in a variety of projects in Istanbul, including Hagia Sophia and the Kariye Camii (Chora Monastery), one of the finest surviving Byzantine churches. In particular, he worked with Ernest Hawkins, an outstanding conservator who had gone to Istanbul to work for Whittemore, studying the famous apse mosaic at Hagia Sophia, the Fethiye Camii (St Mary Pammakaristos church) and the Fenari Isa Camii (monastery of Constantine Lips).

Cyril was also involved with his friend Ihor Sevcenko in the identification of the ruins of St Polyeuktos, the greatest church in Constantinople before the rebuilding of Hagia Sophia by the Emperor Justinian, which Cyril subsequently arranged to be excavated. In the mid-1950s he made field trips to Macedonia, and later expanded his researches to Cyprus, Mesopotamia and Syria.

The resulting publications brought into play all relevant evidence – architecture, inscriptions, mosaics, saints’ lives or the accounts of medieval travellers. In the case of Hagia Sophia, this included the Swiss archive of the Fossati brothers, who had been employed by the Ottoman Sultan to carry out restoration of the church in 1847, which provided new information about the mosaics.

In 1972 he published The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453, and he went on to produce more popular works such as Byzantine Architecture (1974), Byzantium, the Empire of New Rome (1980) and The Oxford History of Byzantium (2002). His enormous output established Byzantine studies as a new and flourishing endeavour, continued by students and academics that he inspired and taught.

Born in Istanbul, Cyril was the third son of Ada (nee Damanov), a refugee from the Russian revolution, and Alexander Mango, who had studied law in Britain and practised in Istanbul, including as legal counsel to the British ambassador. The family belonged to the swiftly declining world of the Istanbul Greek community, which went from being economically powerful under the late Ottomans to being systematically reduced in every way under the early Turkish republic. The common language of Cyril’s parents was French, so their children learned to speak that language, as well as Russian, Greek, English and Turkish.

On a family holiday on the Princes’ islands in the Sea of Marmara, to which members of the Byzantine imperial family had once been exiled, Cyril was fascinated by the remains of the monasteries. His interest grew to the extent that while a schoolboy in Istanbul his erudition impressed the Swiss scholar Ernest Mamboury and the British historian Steven Runciman. The latter, similarly precocious and polyglot in his youth, found his patience taxed by Cyril’s readiness to make his knowledge available: no one seemed to know more, for instance, about the Great Palace.

From the English high school for boys Cyril went to St Andrew’s University in Scotlandand gained an MA in classics. At the Sorbonne in Paris he completed a doctorate in 1953.

There followed a number of posts at Dumbarton Oaks, culminating in an associate professorship (1962-63). He became professor of modern Greek and Byzantine history, language and literature at King’s College London (1963-68). Then he returned to Dumbarton Oaks for five years, before taking up his final post, as professor at Oxford (1973-95). In 1976 he was appointed a fellow of the British Academy.

Until suffering a stroke in 2016, he never stopped writing and researching, adding to a corpus of dated Byzantine inscriptions that he had begun in 1978 with Sevcenko, and increasingly concentrating his researches on Byzantine Constantinople. It is hoped that his work on these subjects will be published posthumously.

In 1953, he married Mabel Grover, and they had a daughter, Cecily. In 1964 he married Susan Gerstel, and they too had a daughter, Susan. Those marriages ended in divorce, and in 1976 he married Marlia Mundell, later a lecturer in Byzantine archaeology and art at Oxford. She and his daughters survive him. »