While prior to Oct. 7 the Turkish leader was viewed favorably among wide swaths of Palestinians for his harsh rhetoric against Israel, many now say he’s done too little since the outbreak of the war.

Al-Monitor, June 1, 2024, by Amberin Zaman

When rogue officers sought to overthrow Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in a bloody coup in July 2016, crowds of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank took to the streets in protest, then celebrated when the coup failed, in a show of solidarity with their favorite Muslim leader.

Erdogan’s unstinting support for the Palestinian cause — so memorably on display at the 2009 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where he clashed on stage with then Israeli President Shimon Peres over Israel’s offensive on Gaza — elevated him to hero status among pious Muslims worldwide. From supermarkets in east Jerusalem to private homes in Gaza City, images of Turkey’s first Islamist president, lovingly framed, became ubiquitous. Newborns were named after him. Erdogan’s popularity among Palestinians soared above his own ratings at home.

Since the Gaza conflict erupted in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7 assault on Israel, the mood has shifted dramatically. The posters have disappeared, disappointment has set in. “Before I used to think Erdogan was the best. People here loved him. From Ottoman times, Palestinians look at Turkey as the father state and saw Erdogan as the man who can support Palestine throughout the world,” said Abdes Salam Abu Khalaf, a public relations consultant in the West Bank, recalling that the Ottomans ruled over Palestine for more than 400 years. “During the [May 2023 presidential] election [in Turkey], Palestinians were glued to their phones, awaiting the results, praying for him to win,” Khalaf told Al-Monitor. “Now we see his true face.”

“He did good things for Turkey and good things for us, for Muslims,” said Joumana Nacha, a shop assistant at a garment store in Hebron, noting Erdogan’s successful campaign to defang Turkey’s anti-Islamist military and the rolling back of bans on overt expressions of piety, notably on the Islamic headscarfs for women in government and schools. “He finished Ataturk,” she said, referring to the pro-secular founder of modern Turkey. “Today, I can say he is finished for me,” Nacha told Al-Monitor.

“Before Oct. 7, a lot of Palestinians adored him. But after Israel’s attacks he was silent for too long,” Islam Hirbawi, the store owner, concurred.

To be sure, in the early days of the conflict, and to the relief of Turkey’s Western partners, Erdogan refrained from his incendiary rants against Israel, offering instead to mediate between Israel and Hamas. “We invite all parties to act reasonably and avoid impulsive steps that provoke tensions,” Erdogan said. On Oct. 10, he appealed to Hamas to free Israeli hostages. As footage of the horrors Hamas had inflicted began surfacing, Turkey reportedly asked visiting Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh to leave. Turkish officials denied the claim. But the claims stuck.

Erdogan maintained his cautious stance even as Israel began hitting Gaza, killing a growing number of women and children. This was attributed to Turkey’s efforts to mend ties with the West after a period of prolonged tensions that left the country increasingly isolated in the midst of a sharp economic downturn. The effort included restoring diplomatic ties with Israel to ambassadorial level. Economic ones never suffered and were indeed flourishing. Just weeks before Oct. 7, Erdogan met with his longtime bugbear, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, for the first time on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Erdogan was to mark the centennial of the Turkish Republic with prayers at the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. Netanyahu was to meet with him in Ankara. Meanwhile, certain Hamas and Muslim Brotherhood operatives, long welcome in Turkey, were being quietly told to leave.

But as the death toll in Gaza rose, the balancing act became untenable. Following the Oct. 17 rocket explosion at Gaza’s al-Ahli hospital that killed a large number of civilians, Turkey declared three days of mourning. Then on Oct. 25, Erdogan declared before the Turkish parliament that he had canceled his trip to Israel. The Jewish state was, with Western backing, committing war crimes, and Hamas was not a terrorist outfit but rather “a group of liberators defending their land,” Erdogan said. On Nov. 4, Ankara declared that it was withdrawing its ambassador from Tel Aviv after Israel recalled its own envoy for consultations.

Nearly 10,000 Palestinians had died by then in Israeli attacks on Gaza and the West Bank. “It was too little, too late,” Fawaz Rajab, a Palestinian engineer in Hebron, told Al-Monitor. “Turkey should have immediately cut all ties with Israel, diplomatic, trade, everything. It should have declared war on Israel,” Rajab asserted. « The Muslim armies should act to protect their brothers in Islam. If I were Erdogan, I would move my army against the state of Israel. This is what we expect from the men in power, » Mustafa Shakir, a member of Hizb ut-Tahrir, a global pan Islamic Salafi movement, told Al-Monitor.

It is a measure of just how much faith Palestinians placed in Erdogan that their expectations of him run so unrealistically high, Khalaf explained.

It may also be that many fell for the fake videos that began circulating on social media claiming that Erdogan had vowed to respond militarily if Israel attacked Gaza. It didn’t help that Turkish whistleblower Metin Cihan began sharing open-source data that displayed the extent of Turkey’s trade relations with the Jewish state, which totaled $9.5 billion annually in 2022 and was largely in Turkey’s favor. Some of the goods, again based on open-source data, were being carried by a ship owned by Erdogan’s younger son Bilal, Cihan revealed.

It wasn’t just Palestinians who felt betrayed. Back home, members of Erdogan’s pious base were appalled by footage of Turkish police beating and attacking anti-Israeli protestors, among them women wearing the hijab. Many conveyed their anger by defecting to a small Islamist party, New Welfare, that mauled Erdogan’s Gaza policy in the run up to the March 31 local elections and more than doubled its share of the vote, largely at Erdogan’s expense.

“Gaza was an important factor in the shift away from Erdogan to [New Welfare leader Fatih] Erbakan,” Ozer Sencar, founder of Metropoll, an Ankara-based polling organization, told Al-Monitor. “His ratings are his lowest since coming to power [in 2003],” Sencar added.

The message wasn’t lost on his inner circle either, notably his wife, Emine, a fellow champion of Gaza, and his elder daughter, Esra, who insider sources claim told him “we lost the elections because of Gaza.” It was they, the sources said, who convinced the Turkish president to cancel his long-sought meeting with President Joe Biden at the White House, which was due to be held on May 9.

In April, as pressure mounted, Turkey announced it had restricted the sales of 54 items to Israel, such as iron and steel products, jet fuel, construction equipment, machines, cement, granites, chemicals, pesticides and bricks.

Erdogan’s rhetoric grew steadily harsher as he hosted Hamas leaders Khaled Mashal and Ismail Haniyeh anew. On May 2, Turkey said it was ceasing all trade with Israel until its war against Gaza ended and aid to the enclave can flow unhindered. Israel relied heavily on Turkish construction materials. However, trade officials speaking to Reuters said they expected that Greece, Italy and other countries were “willing to fill the vacuum.” « Turkey is a significant trade partner of Israel, but we do not rely exclusively, or even remotely exclusively, on Turkey, » Shmuel Abramzon, chief economist at Israel’s Finance Ministry, told the news agency.

Today, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan said he expected Turkey to apply to join South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice in June. Also today, a network of activists who call themselves the “Tent of Resistance” and have vowed to “remain on the streets until all ties to Israel are severed” gathered outside the Istanbul headquarters of Azerbaijan’s state petroleum SOCAR to protest its continued supply of jet fuel to “the Zionist aircraft while tens of thousands are being slaughtered in Gaza.”

Azerbaijan meets an estimated 40% of Israel’s oil needs through a pipeline that runs through Georgia onto export terminals on Turkey’s Mediterranean shores. Ankara has so far ignored calls to halt the flow, a step that would have a far bigger impact on Israel than any of those taken by Turkey up to this point. Earlier this week crowds gathered outside the Israeli and American consulates in Istanbul, chanting “down with Israel.” Some hurled fireworks at the Israeli mission.

Some Arab analysts say they aren’t surprised by Erdogan’s actions. “He flipped his positions so many times in the past two decades,” Ayman Abdel Nour, a liberal Syrian commentator noted. A passionate advocate of the late Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi who was ousted in a military coup, Erdogan has since kissed and made up with his tormentor, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi.

Similarly, he’s sought to patch up relations with Syria’s Bashar al Assad after arming and hosting Sunni rebels who unsuccessfully tried to oust him, while telling Turkish voters that he’ll send millions of Syrian refugees home. “He is ready to use the Palestinian card and the Brotherhood card to his advantage. People now understand that his real policy is to keep himself in power,” Nour told Al-Monitor.

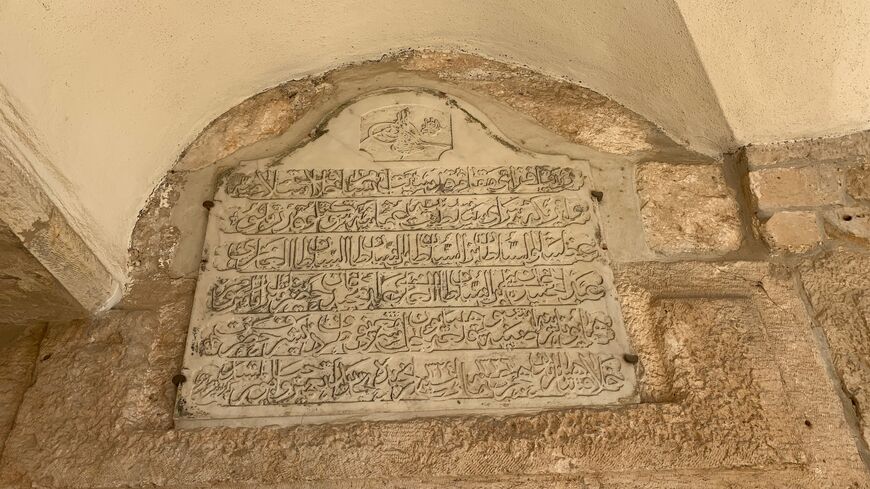

Ottoman inscription dating back to Ottoman rule over Palestine in the 17th century, Tower of David, Jerusalem, May 24, 2024. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Hebron is a bastion of Hamas support and, until recently, was a bastion of Erdogan support. Youths wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the crimson Turkish flag whizz past on bicycles. Shops with names such as “Istanbul Style” or simply “Turkish” line the main commercial drag. Not everyone judges Erdogan as harshly. Tareq Aziz Shuqair is director of engineering at Hebron municipality, which has received training and funding from Turkey for numerous projects, including for the local fire brigade. “When you look at the rest of the Muslim leaders in Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and elsewhere, Erdogan is still one of the best for the Palestinian people,” Shuqair told Al-Monitor. “He did the minimum of what we expected of him. But at least he did it. What did the others do?” he asked.

Khaleel Assali, a prominent Palestinian commentator, agrees. “What President Erdogan and the Turks in general are doing for the benefit of Gaza and the Palestinians is much more than what all the Arab countries are doing combined,” Assali said. “Despite Palestinian anger stemming from the mismatch between their expectations and the Turkish response, Turkey still enjoys a high status, and Erdogan’s popularity far outstrips that of some so-called Palestinian leaders,” Assali added.

Back at the garment shop, store owner Hirbawi said that well after Turkey’s blanket trade ban, he continues to import goods from Turkey. “Ten days ago [on May 11] I ordered 20 cases full of scarves from my supplier in Istanbul. They arrived at Haifa port,” Hirbawi said. “Erdogan is doing what is in his interest, in the interest of his own country,” Hirbawi concluded.