It’s now easy to forget that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was once hailed as the paragon of a “Muslim democrat,” who could serve as a model to the entire Islamic world. By Christian Oliver in Politico on May 3, 2023.

In the early 2000s, hopes ran high about the charismatic, lanky, former football striker, who received only one red card in his playing career, unsurprisingly for giving an earful to a referee. The man from the working-class Istanbul neighborhood of Kasımpaşa promised something new: Finally, there was a master-juggler, who could balance Islamism, parliamentary democracy, progressive welfare, NATO membership and EU-oriented reforms.

That optimism feels a world away now, as Turkey heads into crunch elections on May 14 marked by debate over the centralization of powers under an increasingly authoritarian and divisive leader — dubbed the reis, or captain. Prominent opponents are in jail, the media and judiciary are largely under Erdoğan’s thrall and the kid from Kasımpaşa now rules 85 million people from a monumental 1,150-room presidential complex he built, commonly referred to as the Saray, meaning palace.

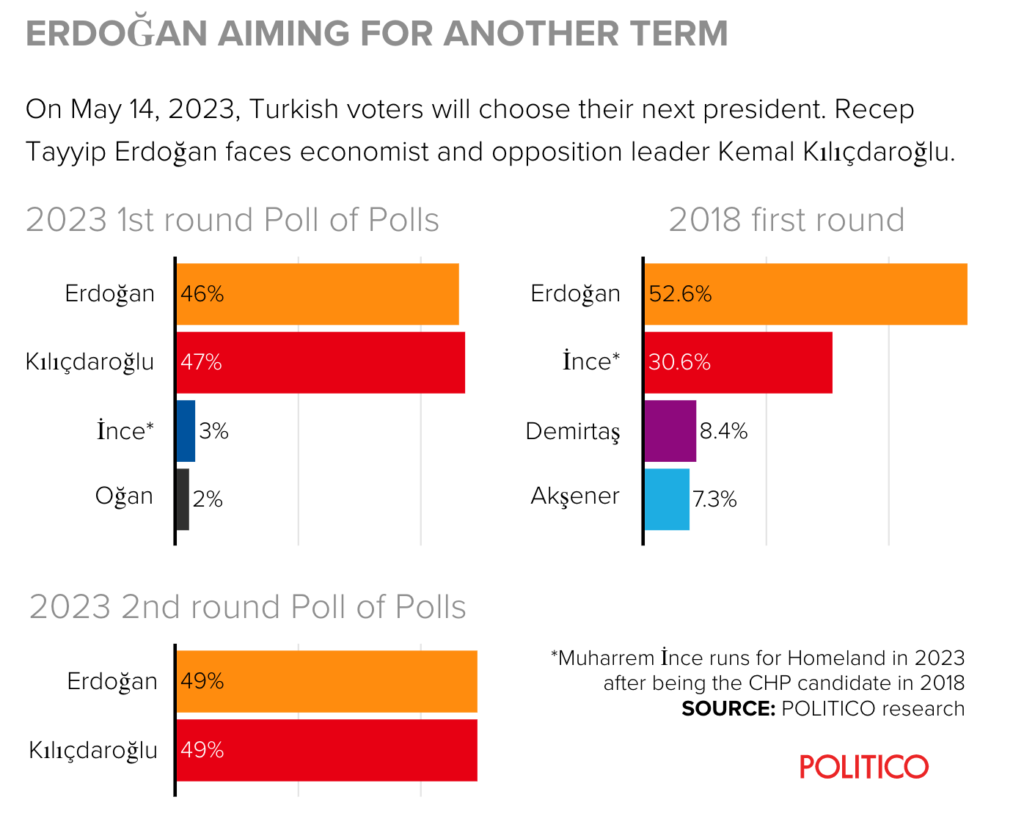

Little wonder, then, that the opposition is focusing its campaign on undoing the “one-man regime.” The six-party opposition bloc is vowing to take a pick-ax to the all-powerful presidential system Erdoğan introduced in 2017 and to shift to a new type of pluralist parliamentary democracy. (POLITICO’s Poll of Polls puts the contest on a knife edge, meaning there will probably be a second round in the presidential vote on May 28.)

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the opposition leader challenging Erdoğan for the top job, describes the restoration of Turkish democracy as the “first pillar” of the election race. “In a manner that contradicts its own history … our veteran parliament’s legislative power has been consigned to the grip of the one-man regime,” Kılıçdaroğlu, an avuncular, soft-spoken former bureaucrat, said in a speech on April 23 commemorating the founding of parliament.

Know your onions

But is this talk of democratic restoration seizing the imagination in an election that is, quite literally, about the price of onions and cucumbers?

Turkey’s brutal cost of living crisis is the No. 1 electoral battleground. Kılıçdaroğlu hit a nerve when, onion in hand, he delivered a warning from his modest kitchen — no Saray for Mr. Kemal — that the cost of a kilo of onions would spike to 100 lira (€4.67) from 30 lira now, if the president stays in power.

Stung, Erdoğan insisted his government had solved Turkey’s food affordability problems, saying: “In this country, there is no onion problem, no potato problem, no cucumber problem.” But most Turks know Kılıçdaroğlu’s arithmetic is not outlandish; he is an accountant by training, after all. Annual inflation hit a record high of 85.5 percent last October, and ran at just over 50 percent in March. The Turkish lira has plunged to 19.4 to the dollar from about 6 to the dollar in early 2020.

In contrast to those bread-and-butter campaign issues, the main thrust of the opposition’s manifesto for switching power away from the presidency sounds legalistic. There are provisions to end the president’s effective veto power, ensure a non-partisan presidency and impose a one-term limit. Parliament will be strengthened by measures ranging from a lower threshold for a party to enter the assembly to greater use of independent experts in committees.

Important reforms, certainly, but will they strike a chord with voters? They could well do. İlke Toygür, professor at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, observed that while constitutional reforms might not be the “daily conversation,” the big themes of one-man rule and Turkey’s historical attachment to parliament did resonate.

One-man rule, for example, is widely linked to mismanagement of the economy and skyrocketing prices, she noted. Erdoğan has been lambasted for pouring fuel onto the inflationary fire by advocating for slashing interest rates — a stance euphemistically described as “unorthodox.”

“If you link everything to each other and link the one-man rule to the cost of living crisis, to the democracy crisis, and to all the problems in foreign policy, then you are defining this system and you are providing an alternative,” she said.

Toygür also stressed parliament played a crucial role in creating Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s independent Turkish republic a century ago, and that still counted. “Parliament has a very strong symbolic value in Turkey,” she said, adding that voters appreciated teams in decision-making, something that Kılıçdaroğlu is playing up. “One of the biggest complaints now is that people lost their links to decision-making candidates.”

In stark contrast to the image of Erdoğan as the lone almighty reis, Kılıçdaroğlu portrays himself as building consensus, ready to draw on a broad pool of talent. In videos, he shows himself discussing earthquake-resistant construction, education and nutrition with high-profile mayors, Mansur Yavaș from Ankara and Ekrem İmamoğlu from Istanbul, his vice-presidents in the wings.

What’s more, Kılıçdaroğlu has pushed this vision of himself as an inclusive leader to a dramatic new level by publicly declaring himself to be an Alevi, a member of Turkey’s main religious minority that long suffered discrimination. His Twitter declaration on his identity, in which he called on young Turks to uproot the country’s “divisive system,” went viral. It’s a risky gambit against a populist president from the Sunni mainstream, but the message is clear: Kılıçdaroğlu is styling himself as the pluralist antidote to Erdoğan’s polarizing politics. The humble 74-year-old may be a bit dull after the caustic current leader, but the opposition’s gamble is that’s what Turkey needs.

Power to the president

Most observers looking back to identify a turning point where Erdoğan decided to centralize power around himself select the Gezi Park protests of 2013, when an unusually socially diverse band of demonstrators sought to stop a green space in Istanbul from being bulldozed for a shopping mall.

The protests — eventually smashed with tear gas and water cannon — swelled into a nationwide roar against Erdoğan’s cronyism and strongman style. Demir Murat Seyrek, adjunct professor at the Brussels School of Governance, said it was the first time Erdoğan felt “the threat was against him” rather than the ruling AK party.

The final straw was an attempted coup in 2016 — the facts of which remain opaque — that pushed Erdoğan to hold a referendum in April 2017 on shifting to a presidential system. He won by the narrowest of margins (51.4 percent) and the opposition still disputes the result, not least because the vote was held during a post-coup state of emergency.

Seyrek noted the irony that the presidential system also had downsides for Erdoğan, particularly as he requires 50 percent of votes (+1) to stay in office. Now deserted by bigwigs from his AK party’s early days — former President Abdullah Gül and former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu have turned against him — he has to find increasingly extreme partners for his coalition to make up the numbers. “Each time, he wins by losing political power to other parties. He is winning by sharing power with more and more people,” he remarked.

A hardened political brawler, Erdoğan is punching back hard against the accusations that he’s the man undermining Turkish democracy.

As he has done for years, Erdoğan is turning the tables and casts himself as the voice of the majority, underlining Islamic propriety and family values, while saying his adversaries are in hock to terrorists, the imperialist West, murky international high-finance and LGBTQ+ organizations. Mainstream rival parties are dismissed as fascists and perverts, and he predicts his voters will “burst” the ballot boxes with their tide of support on May 14.

In an episode typical of Erdoğan’s combative instincts, he scented blood when Kılıçdaroğlu was photographed stepping on a prayer rug in his shoes at the end of March. Although his rival apologized for this unwitting accident, the president whipped up a crowd to boo him, accusing Kılıçdaroğlu of taking his instructions from Fethullah Gülen, the U.S.-based preacher and former AK party ally, whom Erdoğan now accuses of inciting the failed coup in 2016.

Clutching a prayer rug himself, Erdoğan intoned through his microphone: “This prayer rug is not for standing on with shoes. God willing, we’ll be able to perform the prayer of thanks on this prayer rug on May 15.”

Opposition politicians know full well they can easily be typecast by Erdoğan as reactionary voices of an old elite. That’s why they are being careful not to describe their proposed constitutional overhaul of the presidency as turning back the clock to some fictional glory days, but rather as creating something new: What the opposition manifesto calls “a truly pluralistic democracy” that “has never been possible” before.

Free but not fair?

Given the fears about Erdoğan’s lurch toward authoritarianism, speculation is intense over how fair the elections will be, and whether Erdoğan can rig them. Indeed, Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu only fanned the concerns that the government could crack down on the democratic process by describing May 14 as an attempted “political coup” by the West — hardly words to be taken lightly given Turkey’s history of putsches.

With the full resources of the state and pliant media at his disposal, the president can certainly command disproportionate influence. In only the past few days, for example, Erdoğan has been able to offer free Black Sea gas as a pre-election perk.

But Seyrek at the Brussels School of Governance stressed that voting itself in Turkey should never be compared with Russia or Belarus. He argued the vote in each polling station would be closely monitored by all the political parties and other civilian observers. “I still feel in Turkey, what you can do against the result of elections is quite limited,” he said.

The consensus is that Erdoğan will be unable to fix the result in the case of a significant defeat. The greater danger, as noted by several analysts, is that he could attempt some high-risk stratagem in case of a tight result, demanding a recount or calling a state of emergency in case of some diversionary “incident.” That would, however, only inflame the country’s febrile politics just as Ankara needs stability to attract foreign investors and resuscitate the economy.

The more surreal idea — but not an implausible one now — is that Erdoğan could tactically see the time is ripe to lead the opposition and attack Kılıçdaroğlu’s new government. The new president would be highly vulnerable to Erdoğan’s vitriolic rhetoric as he tries to hold together a fissiparous coalition in the teeth of an economic crisis. Paradoxically, though, Seyrek noted that the AK party members in opposition could even support reforms to shake up the presidency and ensure media freedoms, as that would be in their interest. That could prove important as constitutional change would need a hefty parliamentary majority.

Or would Erdoğan simply take umbrage in defeat and quit the country?

Seyrek found that inconceivable.

“In his mind, he is a second Atatürk, he would rather die than escape.”