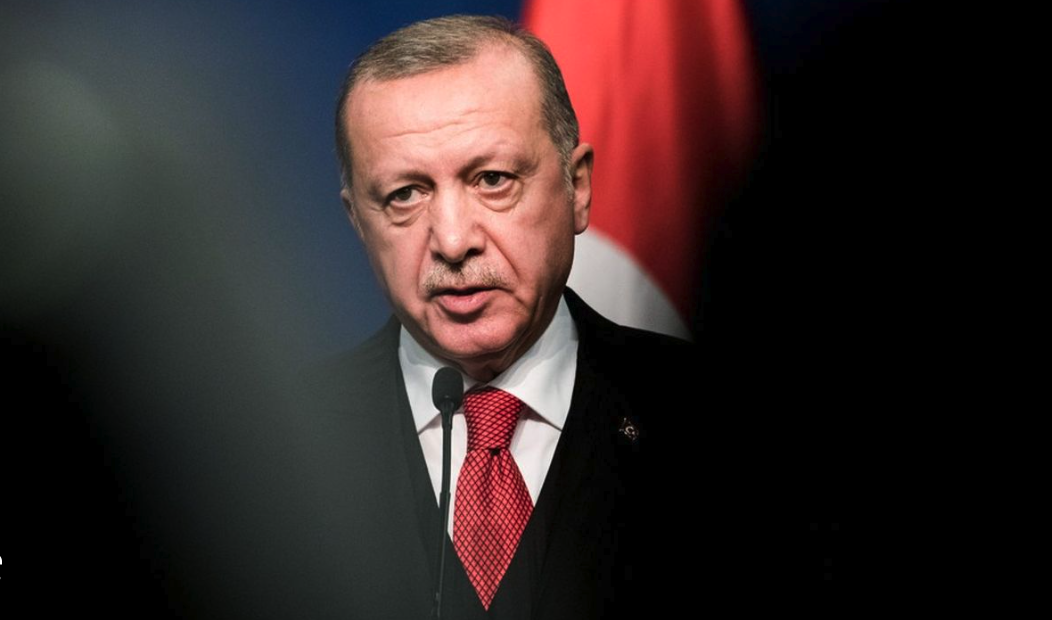

Erdoğan, personally, is compelled to win these elections. If he loses them, he would most certainly face the high criminal court to answer for massive corruption charges, including those pending in the US, and to be accountable for countless violations of the constitution and the laws during his twenty years of tenure. By Cengiz Aktar in Free Turkish Press on April 10, 2023.

On January first the centenary of the Republic of Turkey commenced. In many ways 2023 will be momentous, as it is also an election year during which the fate of Turkey—as well as the nature of its relations with the world—would be affected for the years to come.

The coincidence is one of the five fundamental reasons why president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan might be re-elected.

His ideology considers an electoral victory during the centenary as a vital message to the country and to the world that “New Turkey”, as opposed to the current one created by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is now consolidated and here to stay. Symbolically, that would mean the paroxysm of the regime’s de-westernization drive and the preponderance of Erdoğan over Atatürk.

One should not underestimate the symbolism of 2023 for Political Islam, as opposed to 1923 which was the consecration of the then centenary of the westernization began early in the 19th century, and which has advanced blatantly at the expense of Islam.

2023 therefore means, for Erdoğan and his constituency, a paroxysm of revenge and the beginning of a “rebirth” based on a strong anti-Western rhetoric – a rebirth the regime has already started to publicize as the “Century of Turkey”.

On the other hand, Erdoğan, personally, is compelled to win these elections. If he loses them, he would most certainly face the high criminal court to answer for massive corruption charges, including those pending in the US, and to be accountable for countless violations of the constitution and the laws during his twenty years of tenure. The same threat goes regarding the military campaigns in neighbouring countries Iraq, Libya and Syria within the framework of the “the International Criminal Court”. One should add to these breaches his well-known support for ISIS.

Erdoğan may simply not take that much of a risk, and therefore needs to conserve his immunity. In other words, he and his cronies may not dare to accept the challenge of an “electoral competition” that they may lose.

A similar risk runs for his followers. Indeed if Islamists lose these elections and quit power they are conscious that they will never be able to come back at the helm of Turkey again as their executive record is literally cataclysmic.

The second reason he may be re-elected stems from the shortcomings of the opposition. The opposition, with the obvious exception of the pro-Kurdish party HDP, didn’t manage to present a strong candidate. The official candidate, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, looks no match to Erdoğan’s still appealing charisma, which extends beyond his own constituency.

Moreover, the opposition’s joint “programme for government” consists basically of one hard fact: Getting rid of Erdoğan, and accessorily, avoiding to be seen coalescing with HDP and the Kurds in general.

In reality, the opposition parties are waiting for the ruling coalition to fail the elections instead of working to win them. That obviously does not go far enough to reach the dissatisfied masses, particularly the youth and obviously HDP voters.

The weakest link of the opposition, the ‘Good Party’ (IYIP)—which is a mere avatar of Erdoğan’s coalition partner the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP)—remains prone to shift sides after the elections and become the coalition partner of Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), in the new legislature.

Finally, foreign policy remains the main area where the regime holds all the cards to manipulate and neutralize the opposition. The opposition is in fact more hawkish than the regime on foreign adventures. On the way to the elections, the regime can effortlessly disarm the opposition’s enthusiasm for foreign wars by itself launching another foreign military operation in the neighborhood—possibly Syria.

The third set of reasons consists of Erdoğan’s own constituency, whose motives cannot be reduced to a sort of utilitarianism based on the widespread clientelism and charity the regime established over the years. The pro-regime masses agree with Erdoğan’s non-democratic policies and dictatorial ways of governing.

This piece was in fact penned before the devastating Syria-Turkey earthquake and the adequate response Ankara’s rulers failed to provide. The devastating nature of both the earthquake and the response were expected to produce a huge shift in voting intentions in favor of the regime, therefore guaranteeing a landslide for the opposition. Despite early drops, no significant effect on voting intentions has been registered.

To the contrary, the gauge has almost got back to pre-earthquake times. This unusual voter behaviour needs to be deciphered. In any normal country such an occurrence would have triggered a total setback for the ruling authority. In Turkey nothing of the kind happened, at least according to the opinion polls. It could be argued that the Erdoğan regime’s rock-solid constituency is similar to the unwavering mass support enjoyed by some of the 20th century’s most despised totalitarian regimes.

The same masses, though economically dissatisfied, see no alternative to Erdoğan who has by now started electioneering through his special election handouts thanks to the cash support of his external supporters. The whole economy is now geared towards securing an impression of opulence during the pre-electoral period.

The fourth set of reasons is Erdoğan’s external support. There is now ample commitment by oil-rich dynasties of the Middle East, as well as Putin, to support Erdoğan and Turkey’s ailing economy to ensure the re-election of their favorite. It’s enough to watch the unusually massive share of “error and omission” items on the national accounts in order to track dark money from unidentified sources. Putin’s enchantment is particularly noteworthy, as he sees a golden opportunity to continue to sow discord in NATO with a disruptive Erdoğan.

Yet it is not merely the non-democracies who support Erdoğan. The West supports him indirectly by “understanding” the regime’s aggressive and autocratic behavior in and outside the country, deriving from largely fictional “legitimate security concerns”.

Erdoğan’s extravaganza, his eternal victimhood, his threats towards NATO ally Greece, and his military operations against the Kurds in Iraq and Syria were all “understood” by his backers in the US, NATO and the West in general. The same complaisance goes for Erdoğan’s Russia policy, which cajoles Putin on the one hand by economically shouldering him, and on the other, pretending to be a friend of Ukraine.

The West is, all things considered, quite powerless in the face of Erdoğan’s gunboat diplomacy, his unilateralism and his double-play. It’s been years since we first started witnessing this appeasement policy, which is based on the fear to ensure Turkey’s presence within NATO and so to limit its Russian temptations at any cost.

The final set of reasons Erdoğan may be the winner in 2023 is his electoral engineering, through which nothing is left to chance. Indeed, if an unforeseen push by the opposition gives it an edge on Election Day, that advantage could be overturned by the electoral body that Erdoğan controls, and the elections stolen as in in Belarus in 2020.

First: electoral engineering has been underway since the loss of the six metropolitan municipalities in March 2019, and encompasses the electoral bureaucracy, the electoral constituencies and the relevant laws and regulations.

The appointment of pro-regime judges to the Supreme Electoral Council (YSK) is already in place. The chairpersons of the electoral commissions will be composed of regime-appointed judges. Thus, the ballot boxes and electoral commissions will be under the direct control of the regime.

The Council and the electoral commissions could reject candidates on any pretext and could even reject alternates to be nominated in place of the rejected ones, thus leaving the opposition parties without candidates in many constituencies. They would then be unable to nominate candidates on time and thus unable to participate in the elections in a given constituency.

The requirement to reside in a dwelling for a minimum period of three months in order to vote would put 2.5 million university students (who will vote for the first time) at risk of not being able to go to the polls. Similarly, in earthquake-affected provinces already some 1.6 million voters have not been able to register themselves somewhere else.

As for the vote counting, the Council has partnered with a corporation belonging to a Turkish Armed Forces foundation that specializes in defence and software, Havelsan. No crystal ball is needed to predict the likely result. And there will be no course to appeal the decisions of the YSK.

Second: the continued presence of Süleyman Soylu at the Ministry of Interior and the reappointment of radical Erdoğan subordinate Bekir Bozdağ to the Ministry of Justice are strong assets to tightly control the system and the country. The deadly terrorist attack in the centre of Istanbul on 14 November 2022, whose perpetrators strongly and skeptically questioned by the leftist opposition press, should be seen as an harbinger of things that may come.

The regime’s semi-official armed mobs will also be on duty during the election season. Let’s not forget that Erdoğan has at his service a huge armada comprised of a 340,000-strong police force, over 100,000 Kurdish village guards, over 100,000 Syrian and other jihadists, in addition to a plethora of regular and irregular armed groups.

Third: one should read the new legislation on censorship of social media. Here is how Human Rights’ Watch qualifies it: “The timing of the legislation, months before the 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections, also raises concerns that the government intends to muzzle online reporting and commentary critical of the Erdogan government in the run up to the elections.” As in many countries, the youth and top opposition figures are both very active on social media.

Finally, the election campaign will, once again, be over-favoring the regime for the access to Turks’ main source of information: the television channels which are almost exclusively under regime control. According to Reporters Without Borders, the regime controls some 90 percent of all media outlets, which gives Turkey an appalling rank in terms of press freedom: 149th out of 180 countries surveyed.

Despite all these odds, the opposition is possessed by an ever-growing overconfidence in victory. The date for elections, 14 May 2023—the anniversary of the first win of the opposition in 1950 against the Kemalist order—might disenchant. But in case of a miraculous victory by the opposition, there will be no quick fixes to Turkey’s internal or external problems for decades to come. The future ruling coalition, which ranges from centre-left to extreme right, will have a hard time agreeing on any critical issue—beginning with the Kurdish question. Thus some are already evoking the possibility of snap elections before the year’s end.

This article has been published in French (La Revue Esprit) in German (Le Monde Diplomatique-Deutschland), in Greek (Kathimerini) and in Italian (Internazionale). This is an updated version.