« The upcoming Turkish presidential election will have serious but uncertain consequences for the security and humanitarian situation in northwestern Syria. » Pierre Boussel’s analysis in Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on February 16, 2023.

In early February, the Syrian-Turkish border area once again became the center of international news following the deaths of thousands as a result of a massive earthquake that struck southeastern Turkey. The political complexities of the area came to the fore against the backdrop of difficult attempts to coordinate humanitarian aid and rescue efforts. Yet, the humanitarian and security situation in the area has been fragile for years.

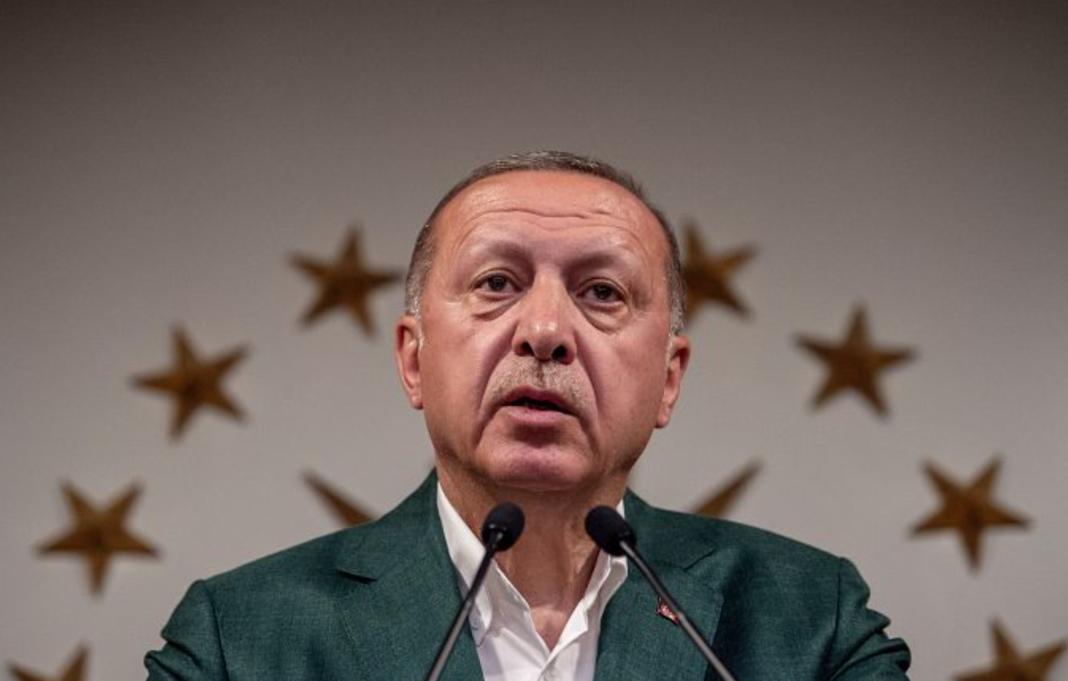

President Erdogan has always made Syria a priority, because it represents both the first circle of his strategic depth and a possible infiltration zone for Kurdish independence fighters. With some polls predicting that the ubiquitous and immovable Erdogan will lose the presidential election to be held on May 14, concern is growing over two key campaign issues: Erdogan’s call for reconciliation with Damascus and the departure of 3.5 million Syrian refugees. Indeed, Erdogan is currently under threat from a coalition of opposition parties, among them the Kemalist CHP—the Republican People’s Party—which is demanding a review of Turkish policy in Syria. Pressed also by his own AKP electoral base, Erdogan has made commitments on these two issues, even if he is hardly in favor of either.

In this context, a program for the return of Syrians is now underway, with 1.5 million refugees in the process of being repatriated to northern Syria. Turkish dialogue with Damascus has also been initiatied under the auspices of Russia despite deep antagonism between the two neighbors regarding Turkish activities in the northwest.

In northwestern Syria, the population has mobilized to express hostility towards Turkey’s new policy of dialogue with the Assad government. The group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), although a Turkish ally, regrets that the Turkish agenda “does not coincide” with the objectives of the Syrian revolution. A coalition of armed groups united under the banner of the Syrian National Army (SNA) also opposes Turkish normalization with the Syrian regime, which they fear could lead to that fratricidal fighting between armed groups in the event of a hasty Turkish withdrawal.

A victory for Erdogan would probably mean a continuation of his current policy in Syria, but in the case of his loss, it is likely that the new presidential team will seek to embody change. Few changes are expected on the anti-PKK struggle, but many questions revolve around Syria. For example, the Turkish army is currently building a helipad at the Baluon base to reinforce its 60 to 80 military posts in Idlib province. If there is a change of government in Ankara, it is not clear whether these posts will be dismantled or reinforced.

Alliances also matter. Armed groups in Idlib province maintain regular contact with Turkish intelligence. They are used to living with the specter of a large-scale military operation against the Syrian Defense Forces (SDF), an option opposed by the Americans and the Russians. It remains uncertain how a possible Turkish rapprochement with Damascus would impact Turkish calculations on the ground. For now, HTS leaders talk about a “wrong path” and reassure themselves that reconciliation is unlikely because of Syrian-Turkish differences related to territorial interference and the role of the PKK.

In the meantime, pragmatism is forcing Syrian armed groups to position themselves for a post-Erdogan era, gradually regaining operational independence on the ground and organizing economic life in the territories they control. The first weeks of 2023 saw an upsurge in fighting in the Kawkabah sector of Idlib province, artillery reinforcements in Sheikh Hadid, and the return of tactics that were thought to be a thing of the past, including suicide attacks on government positions. Furthermore, Ansar al-Tawhid, which had been relatively quiet for some time, is now attacking forces in Damascus. Even Ankara’s close allies, namely the Syrian Arab Army (SAA), have been trying to demonstrate their raison d’être by eliminating suspected al-Qa’ida members.

Displaced people residing in the northwest continue to search for means of survival against a backdrop of intense political uncertainty and acute humanitarian suffering. Syrian refugees in Turkey have also been concerened by Erdogan’s announcement that repatriation efforts will be accelerated as soon as diplomatic initiatives with the Syrian regime produce results.

For years, the situation in northwest Syria has been highly dependent on decisions coming out of Ankara. This remains true now, as refugees, displaced people, and armed groups await the results of the Turkish elections. They know that their futures will be affected by the vote, regardless of the outcome.

Pierre Boussel is a columnist and an associate researcher at the Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS-Paris). His work focuses on armed groups in the Arab world and political Islam.

Pierre Boussel’s analysis in Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on February 16, 2023.