« As 2022 forced the Turkish government to reverse course with regional powers, this election year is expected to usher in even more change in Turkey’s foreign policy » reports Semiz Idiz in Al-Monitor.

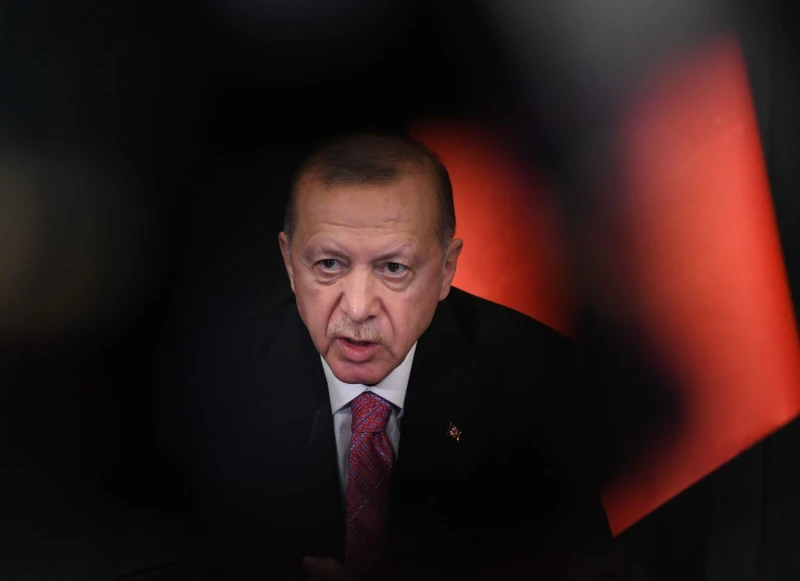

The year 2022 has been one of radical foreign policy reversals by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan when he mended fences with Gulf powers and Egypt, showed readiness to meet Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, and shifted his attention to economic woes ahead of crucial presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey in 2023.

The elections, to take place no later than June, will also bear on Turkey’s foreign policy, especially with regard to ties with the West.

Given the dire state of the Turkish economy, most analysts believe Erdogan will find it difficult to replicate his past electoral success. Erdogan expected the economy to be booming under his rule by now, making Turkey a leading international player and vindicating his one-man-rule in the eyes of domestic and foreign critics.

However, Turkey is seriously at odds with its traditional allies and partners today because of Ankara’s bellicose diplomacy, while its grossly mismanaged economy is in shambles. Turkey’s annual inflation rate skyrocketed to more than 80% over the months of 2022, climbing to a 24-year high. The Turkish lira lost some 30% of its value against the greenback this year. The deepening financial problems are largely blamed on Erdogan’s unconventional economic view. Erdogan has long argued that higher interest rates cause high inflation and under political pressure the Central Bank slashed the country’s interest rates from 14% to 9%through successive cuts from August to November.

As Turkey’s opposition alliance comprised of six opposition parties led by the Republican People’s Party continues to make headway, according to several opinion polls, Erdogan is aware that governments rise and fall on the state of the economy. Turkey’s economy is far more dependent on relations with the West than he has been arguing. The European Union is the main market of Turkish exporters and decreasing European demand fueled by the rising inflation across the bloc have badly hit the Turkish economy, given the country’s gaping current account deficit and foreign debt liabilities in the short term.

With not much assistance coming from the West, though, Erdogan has turned to regional powers for help. In 2022, the Turkish president made a series of dramatic U-turns as he reached out to rich and influential Arab countries he had previously vilified from his pro-Muslim Brotherhood perspective. After the Arab Spring swept several Arab countries in 2011, Turkey’s ties with several Arab countries, notably with Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, have progressively deteriorated due to Ankara’s overt support of the rioting masses. Turkey-Egypt ties have severed after the 2013 Egyptian coup. Ankara’s pro-Muslim Brotherhoodstance also irked Gulf capitals that designated the movement as a terrorist organization along with Cairo in 2014.

Turkey needs at least $216 billion in 2023 to meet its foreign debt obligations and meet its current account deficit.

The deficit, according to retired Ambassador Hasan Gogus, is the main consideration behind Ankara’s new foreign policy orientation.

Turkey “doesn’t want to turn to the IMF, » Gogus wrote in his column for T24. « There is little chance that foreign investors will arrive. No matter how much tourism revenues increase, there is a limit to this. So all that’s left are funds and credits to be secured from rich Arab and Gulf states.”

Erdogan will seek to further deepen ties with the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. He will also try to strengthen ties with Israel in the hope that doing so will also improve his sanding in the United States, all countries he once picked fights with.

In contrast, Erdogan’s ministers accused the UAE of sponsoring the failed coup attempt in 2016, and he vowed to champion “to the very end” the cause of Saudi journalists Jamal Khashoggi, who was murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018.

All of that is forgotten now, and Erdogan has also toned down his support for the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots such as Hamas. Clearly eyeing advantages for themselves, these countries have responded positively to his outreach.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia have transferred billions of dollars to the Turkish Central Bank in response to Erdogan’s requests, with promises of more to come. There is also talk of revived energy cooperation with Israel. Meanwhile, high-level state visits were exchanged in 2022 with Israel, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, during which multiple cooperation agreements were signed.

Erdogan is also trying to reconcile with his regional arch-enemies Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. He had an impromptu meeting with Sisi in Doha during the opening of the World Cup and left happy. He is also calling on Russia to arrange a meeting between himself and Assad.

Talking to reporters during the G-20 summit in Bali in November, Erdogan said there was no place for resentment in international affairs.

“We can reassess our relations with countries we have had problems with, clean the slate after the June elections and continue on our way, » he said.

His remarks astounded many as for years Erdogan had expressed resentment against Egyptian President Abdul Fattah Al-Sisi and Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and vowed never to meet them. Erdogan was angry with Sisi for leading the 2013 military coup that toppled and jailed Egypt’s democratically elected president and Erdogan’s fellow-Islamist Mohammed Morsi.

He also referred to Assad as a “killer” on countless occasions, promising to always champion the cause of the “oppressed” Syrian people. As the Western capitals’ focus in Syria shifted towards fight against the radical jihadi groups by 2013, Ankara remained adamant to its support of the Syrian rebels fighting to oust Assad. It has also kept its borders open to some 4 million Syrian refugees fleeing the civil war. Efforts to solve the burgeoning Syrian refugee problem in Turkey have likely trumped such promises.

Political analyst Murat Yetkin has no doubt that these reversals are dictated solely by a need to improve the economy in the lead-up to elections.

“If Erdogan found any other way to alleviate the economic crisis he created, and if he was not facing elections that could cost him his seat, would he have resorted to these maneuvers?” he asked in his “Yetkin Report.” “I doubt it very much,” he concluded.

Meanwhile, Erdogan’s chances of securing the kind of support he wants from the West remain remote. The importance he gained to Western governments because of the mediation roles he played following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has not translated into the economic support he needs.

International relations professor Ilter Turan at Istanbul’s Bilgi University said the question to ask is why investments from the West have dried up.

“The reason is the unpredictable business environment in terms of the judiciary and of politics,” Turan told Al-Monitor. “Not only are new investors reluctant to come but companies that have a history in Turkey, such as automaker VW, are reluctant to embark on new investments.”

Turkey’s efforts to play on all sides, as in the War in Ukraine, are also problematic, Turan said, explaining, “This is a disincentive because of the possibility of new sanctions on Ankara for not complying with the Russian sanctions.”

Turan does not expect overnight improvement if a new government comes to power after the elections. He believes, nevertheless, that Western foreign investment inflows could resume if there is a sense that developments in Turkey are taking a predictable course and if Ankara shows it will not be fighting with everyone around it anymore.

Considerations about democracy, human rights and the rule of law may play no role in Turkey’s ties in the Middle East. However, they are important for the West so the deep differences over these issues continue to hinder normalized relations with Ankara.

The two-year jail sentence handed to Istanbul’s popular mayor, Ekrem Imamoglu, on the flimsiest of grounds and his banning from politics is the latest example of the state of Turkey’s judiciary. Imamoglu is one of Erdogan’s key political rivals.

Many observers say the co-opted judiciary is trying to clear the field in an attempt to ensure Erdogan wins the elections. They expect more such moves in the days and months ahead.

“This latest example provides a new threshold for [the West] to see how far the government is prepared to go in instrumentalizing the law,” wrote foreign policy analyst Barcin Yinanc for T24. Yinanc pointed out in her column that doubts about the rule of law in Turkey also act as a major disincentive for Western investors.

Turkey’s estranged Western allies and partners will no doubt maintain a cautious wait-and-see stance until Turkey’s elections are over.

Al-Monitor, December 29, 2022, Semih Idiz, Photo/Gent Shkullaku/AFP